U of Chicago Press, 2015

One day, the unnamed narrator of Eduardo Lalo’s epistolary novel Simone begins to receive mysterious, unsolicited notes. Some are left on his windshield, others appear as emails from a beauty academy address. Signed “Simone,” in an apparent homage to the philosopher Simone Weil, the notes mostly contain unattributed quotations:

As he watched the same towns and lonely mines go by, he ran into reminders of his past that transported him to the rest of the world…For a dead man, the whole world was a giant funeral.

The timing of the missives comes just at the moment the narrator, a novelist and teacher at the university in San Juan, Puerto Rico, seems most susceptible — indeed, just as he seems to be dimly viewing the world as a “giant funeral.” His relationships are floundering, he has been having seriously depressive thoughts (“Could the sun be a sort of illness that for centuries has been producing the sensation that life is unlivable?”), and he often eats alone at a Chinese restaurant. His principal occupation seems to be journaling, which provides the structure of the novel. From one such entry:

I’ve always been just as I’ve described myself here: surrounded by fragments, by bits of things with which to fill the hours.

I’ve learned to live amid the rubble, satisfied but not be satisfied, supposing these circumstances link me to a multitude of men and women whom I will make no effort to meet, but with whom I feel a sort of kinship much more powerful than I’ve had with most of the people I actually know…I’ve become a creature of habit and run out of arguments.

The riddle of “Simone” rouses him from this ennui. Who is she and why is she sending these notes? Is she a fan of his novels? Or is she in love with him? Or both?

A similar mystery, in some ways, surrounds Eduardo Lalo, at least to English readers. At the time of this review, a Google search of “Eduardo Lalo” turns up very little in English — only a basic Wikipedia page. One hoping to read more about the author must brush up on one’s dusty Spanish skills. Lalo was born in Cuba, but has lived most of his life in Puerto Rico, studying along the way in both New York and Paris. He is the same age as former Puerto Rican Governor Luis Fortuño, a fact that spawned an essay of his, and he has written several books, many mixing in Lalo’s own drawings. Simone won the Romulo Gallegos Prize — named for the Venezuelan writer — in 2013. (Past winners include Roberto Bolaño, Elena Poniatowska, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and Javier Marías.) Like Simone’s narrator, Lalo teaches at the University of Puerto Rico.

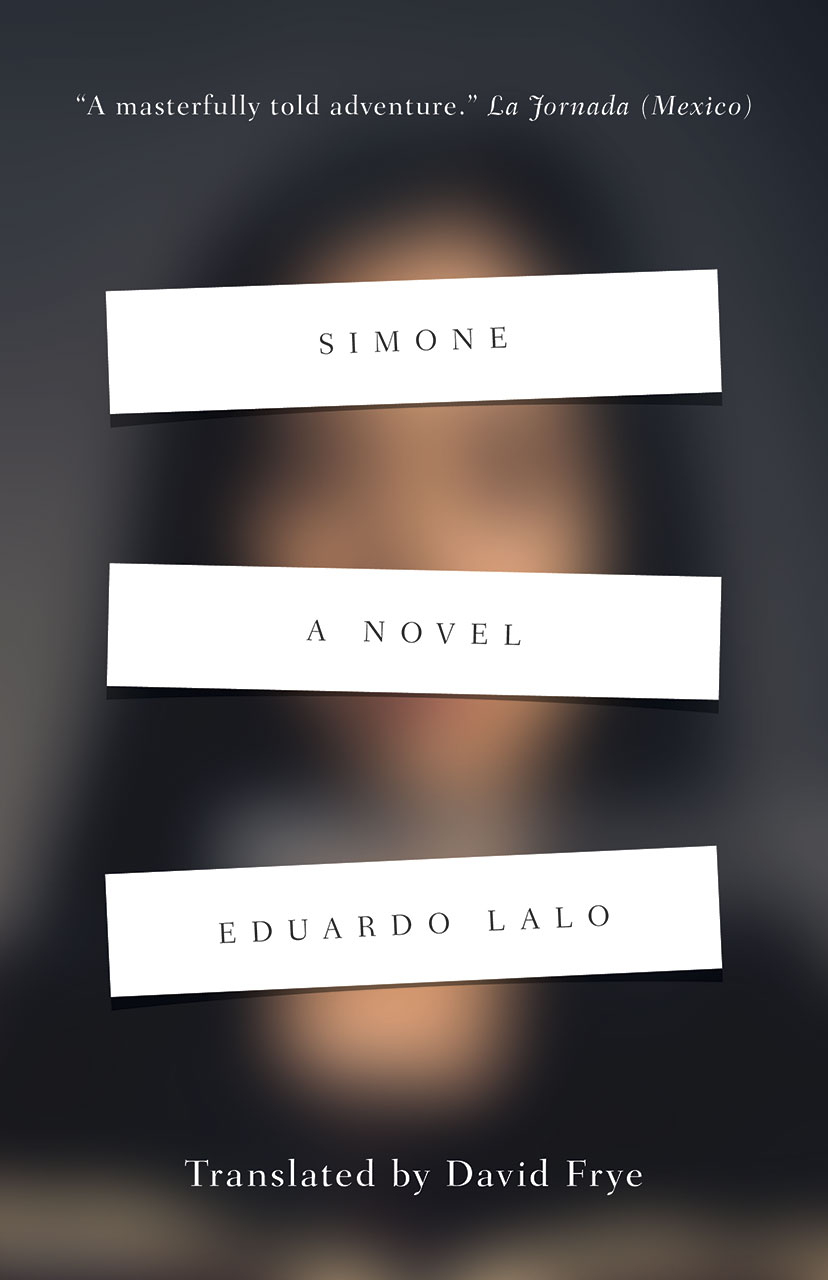

Thanks in part to winning that prize, Simone is finally appearing in English in a beautiful translation by David Frye. To Frye’s credit, Simone never feels like a translation — the language flows easily from sentence to sentence, and contains nothing of the stilted phrasing or flat tone of some translated fiction.

The novel is essentially divided into two parts: before and after the revelation of who “Simone” really is. The first part is shorter and more interesting than the second. It begins with the digressive and often purposefully obtuse entries in the narrator’s diary, reflecting on writing and his own alienation: “[S]truggling and writing are the same thing,” he says at one point, “whether there’s anything to write or struggle against.” Whether it is the world to the author, the author to his text, the text to its reader, there always seems to be a chasm.

Upon his eventual meeting of the mysterious note writer, the book morphs into a fey love story, which proves less successful than the way Lalo circles the existential drain (a testament, in part, to Lalo’s charming, eldritch tone). Even the real name of “Simone” is a cypher, a mask that the woman wears — her identity, perhaps like that of the narrator, is something that she does not truly possess. Her real name, she says, “doesn’t exist,” and she “took to using the words of others to pursue a writer whose failure is eating away at him today.” Receiving an explicit nod here is Walter Benjamin, whose Arcades Project collage seems to inform both “Simone” and Simone.

“Simone” herself admires Simone Weil because “she used to study on her knees.” Weil was famous for quitting her teaching job to work in a factory, part of her effort to understand the conditions of the working poor; she ultimately died because she refused to take additional food rations, despite her tuberculosis. This type of self-induced privation is reflected throughout Simone; “I suffered,” writes the narrator at one point, “so I could write my suffering.” His ultimate problem is that “Simone” herself had it the other — and more traditional — way around: she suffered and then began to write for catharsis.

Just when we have uncomfortably settled into the doomed love story, the book takes a significant turn. Toward the end of the novel, the narrator and a novelist friend of his interrogate a visiting Spanish writer about the literature of the peninsula, and the lower quality work — in their opinion — that many Spanish publishers publish. (There may be some continental agreement to that, as Javier Márias has stated that he had no desire “to be was what they call a ‘real Spanish writer.’”) It is, at first, a strange shift. While the plot is held in abeyance, the book tries to make a larger point about the treatment of literature. In part, the point is that Puerto Rican writers have been unfairly ignored, while more maudlin and unoriginal writings from “real Spanish writers” have received outsized attention.

While the narrator obviously has significant pride in his Puerto Rico, it inevitably comes with a concomitant sense of resentment — part of the dark shadow that follows this novel sentence-by-sentence. Upon seeing the name “Colony Economy” on a carton of milk in a coffee shop, the narrator muses about how Puerto Rico’s history “overwhelms and defines” him. It is an apt lens through which to view Simone — characters who cannot quite escape the world they were born into, or the childhoods they were subjected to, a country shackled by the past and every extension of happiness undercut by sorrow. “What is left of the men and women of this country?” the narrator muses. “What remains but the coffee and the centuries, ground down and percolated, flowing through steel tubes, pouring from plastic spigots?”

+++

+

+