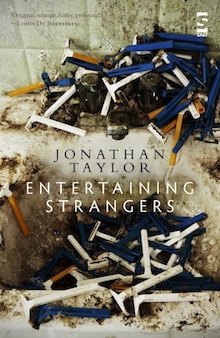

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Jonathan Taylor writes about Entertaining Strangers, a novel out now from Salt Publishing.

+

The title of my novel, Entertaining Strangers, originates from the well-known Biblical verse from Hebrews: ‘Be not forgetful to entertain strangers: for thereby some have entertained angels unawares’ (Hebrews 13, v.2). This is because the two starting-points for the novel were two non-fictional images, one of which involves welcoming strangers, and one of which involves quite the opposite.

The title of my novel, Entertaining Strangers, originates from the well-known Biblical verse from Hebrews: ‘Be not forgetful to entertain strangers: for thereby some have entertained angels unawares’ (Hebrews 13, v.2). This is because the two starting-points for the novel were two non-fictional images, one of which involves welcoming strangers, and one of which involves quite the opposite.

Basically, I started the novel with a ‘memoiristic’ image — a particular memory from many years ago, when my father was in intensive care in hospital, and I was travelling back and forth to visit him from Leicestershire, where I lived at the time. One night when I was back in Leicestershire, I went out and got understandably drunk. On the way home, in the early hours, I felt a tap on the shoulder, and turned to find a homeless woman, who was asking me for some food or money. I said I hadn’t got either on me, but (rather stupidly — I’m older and … erm … wiser now) said she could come home with me, and I’d “feed her the freezer.” I did so, and then she had a bath and slept on our floor to the music of Elgar’s strange piano piece, In Smyrna, which she said she used to play “in a previous life.” Next morning, whilst she was munching burnt toast, my housemate came downstairs; and he immediately started telling her about ants, an obsession of his. He didn’t even notice there was someone new in the house, except insofar as there was another receptacle for his vast knowledge of the fascinating world of ants. Finally, the woman left and kissed us both on the cheeks, saying that she now “believed in English gentlemen again” — one of the nicest things anyone’s ever said to me.

Obviously I know (commonsensically) it was a stupid thing to do to invite someone into your house like that — but it had something to do with my father being in hospital, and the unreality of that life-and-death moment. I never saw the woman again. At the time, she hardly said anything about herself, though it was clear that there was something terrible in her past which had brought her to this point. The episode originally featured in my memoir, Take Me Home: Parkinson’s, My Father, Myself (Granta Books, 2007), but then I cut it out, and returned to it as the primary image for my novel — which is about her (in effect, she’s the narrator) and about a heavily-fictionalised version of my ant-obsessed housemate (who’s the dedicatee of the novel). In part, the research for the novel was an attempt to imagine and reconstruct what her past might have been, from the few clues she supplied.

So my starting-point for the novel, as for the preceding memoir, was ‘truth.’ Despite this shared origin, though, I quickly realised that novel-writing and memoir-writing are radically different. It’s all too easy to believe that literary genres collapse into one another, especially if you work in university literature departments. Certainly, they do overlap, but the research and writing of my novel made me realise, gradually, that they are also separate. The short version of this is that novels need a plot.

Now, this may seem basic, but plot is not something that people talk much about nowadays. Plot is seen as a bit old-fashioned — something that nineteenth-century novels had too much of, and contemporary novels don’t need. But in writing this, my first novel, I realised that plot was of vital importance. In that sense, part of the ‘research’ for the novel was craft-based — it was a finding-out through practice, trial and error, reading and writing, about the differences, in structural terms, between prose genres. Before the novel, I’d written a memoir (as I say) and a lot of short stories. Short stories only need a plot insofar as one thing happens, and something changes for someone. In a novel, though, I soon discovered that one event obviously isn’t enough to sustain 90,000 words of prose. One thing needs to happen every chapter — and in that sense, every chapter is a kind of short story in itself. And all of these chapters, all of these single events, need to link up in some way, and build towards the end. In that sense, a novel is by definition a linear form of writing, even when the linearity is confused (for example, by mixing up chronology).

What I came to realise is that this is a matter of causality, and different genres of writing can be classified according to different attitudes towards causality. A short story encapsulates one moment of cause and effect — something happens or someone does something, and it affects him or her like this, or like that. A memoir, on the contrary, is different — and perhaps more interested in effects than causes. There are, of course, lots of memoirs written in a simple, linear, causal and chronological sequence — that is, “my background was awful like this, I grew up like this, and I progressed to be this important and well-adjusted person I am today.” This kind of progressive narrative is admittedly common, especially in celebrity memoirs. Most contemporary literary memoirs, though, aren’t structured in this way. Instead, chapters in memoirs are often thematised, rather than chronological, grouping together events (or effects) according to subjects, with little or no heed for chronology. Linear causation is often ignored, and if causes for events are sought, they are often elusive. Certainly, memoirists look to the past for connections and links, but these so-called causes themselves often seem like effects. Any simple sense of cause and effect breaks down when faced with the infinite complexities of individual, familial and social histories — to the point that memoirs might seem a bit like literary versions of chaos theory.

What I tried to do in the novel was something different — that is, to write a much more stream-lined, linear narrative, in which each chapter links with and, to some extent, causes the next. Of course, I would never suggest that novels are all like this — but perhaps there is something naturally Newtonian about the novel form (which, after all, grew up in the wake of Newtonian physics), which presupposes a more linear mode of causality.

Gradually, as my novel ‘progresses’ (in inverted commas), a much deeper cause is first glimpsed, and then emerges, from behind all the other stories. Gradually, it becomes apparent that the strange events in the foreground — in, that is, 1997 — are determined by a much more distant event in the main character’s family history, seventy-five years before. I won’t say how, because that would spoil the book. But, in writing the book, it was the challenge that I set myself — a challenge of causality — to link up 1997 and 1922. This was also a matter of linking up a primarily comic, or at least tragi-comic plot (1997), with a moment of intense tragedy (1922).

In the wake of the First World War, Greece was given permission by the super powers to annexe Smyrna (modern Izmir) in what is now Turkey. What followed was a terrible war between Greeks and Turks, with atrocities on both sides. Eventually, this led in 1922 to the resurgent Turkish Nationalists, under Kemal Atatürk, retaking Smyrna and expelling the Greek and Armenian population from Anatolia. What happened in September 1922 is a matter of dispute to this day — most of the city was burnt to the ground, thousands of people massacred, deported, mutilated and raped, and hundreds of thousands of refugees gathered on the quayside screaming for help from the ships in the harbour.

There are numerous non-fictional and fictional descriptions of the tragedy, including some fascinating eye-witness accounts, all of which differ not only in their details, but even in their more general outlines. One image, though, that remains constant in many of these differing accounts is the attitude of the foreign ships in the harbour. The vessels moored there included British, American, French and Italian warships and cruisers; but during the initial stages of the disaster, these ships and their crews stood by, refusing to help the Greeks and Armenians on shore. There are reports, in fact, that sailors from the British ships (working under orders) poured boiling water onto the refugees who swam up to them, begging for help, and played loud gramophone records to drown out the noise.

This was the second main (and non-fictional) image which was fundamental to my novel, as its other starting-point. Like the 1997 image, this image from 1922 is all about hospitality, but, in this case, its failure — a terrible failure, that is, to ‘entertain strangers.’ There’s an extended chapter in the book (about three-quarters of the way through) which flashes back to 1922, and an Armenian girl’s tragedy in the Great Fire of Smyrna. As I say, I won’t reveal here how these two mirror images of hospitality, from 1922 and 1997, link up — how the whole chain of cause and effect between them becomes the novel’s plot. Sufficed to say that the relationship between 1922 and 1997 in the novel might be encapsulated in Karl Marx’s famous epigram, that ‘all facts and personages … in … history occur … twice, … the first time as tragedy, the second as farce.’

+++