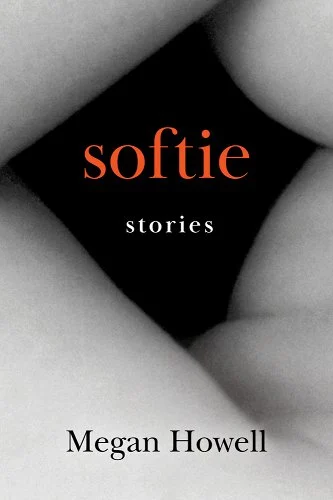

West Virginia University Press, 2024

Writing for N+1, the novelist Raven Leilani has recently observed that while grief resists containment, fiction generally demands it. In her view, a story is a series of exclusions, and storytelling mainly involves decisions about what and does not belong in the story’s container. Softie, a debut collection by Megan Howell, confronts readers with stories of loss and grief that eschew narrative tidiness in favor of detail, digression, and other material that, at first glance, might seem extraneous or irrelevant. With Softie, Howell upends the expectation that stories should be paced as neatly as a grief that proceeds in Kübler-Ross lockstep. Each of Howell’s capacious and surprising stories reveals its complexity like a sturdy coat that, falling open, vouchsafes a flash of satin—a precious individuality, a distinctive point of view.

In story after story, Howell dramatizes conflicts over exclusion and inclusion, who’s in and who’s out. Her characters tend to have soft psychological “boundaries,” to borrow a term from pop psychology. Put upon and pushed around, they avoid abandonment by stoically enduring other people’s incursions, manipulations, deceits, and conceits—to a point. Then they become pushy too. The opening story, “Lobes,” provides a striking example. The protagonist exchanges her habitual submission to a controlling mother—who insists, for instance, on listening in on her daughter’s conversations with a lover—for habitual aggression, nipping that same lover’s earlobe with increasing ferocity until she finally bites it off.

These moments of body horror find equally painful, if less surreal, echoes elsewhere. The title story, in which the narrator’s controlling father, an LA movie mogul, treats his daughter to a birthday dinner she doesn’t want, is a case in point. The father urges the daughter, who is squirming with discomfort, to “quit being such a softie” and “have a good time” instead. The rest of the story shows why this request is impossible. All he does is intrude: “At home he made the chefs guard the kitchen from me when he thought I was overeating; wrapped up my arms in packing tape when he wrongly assumed that I was cutting; fondled my breasts when I told him I wanted reduction surgery.” Virtually nothing of her life is her own; her father has, as she says,“infected” it totally.

The metaphor of infection is exact. Howell’s characters feel oppressively shaped, even defined, by others’ views, which are rarely generous. More often, they are denigrating and cruel. In “Kitty & Tabby,” the eponymous Kitty, a classic mean girl, goads the schoolmates of Tabby, the story’s quiet and awkward narrator, into a frenzy of adolescent cruelty. The circle of viciousness enlarges to include even Tabby’s cousin Carissa, who has succeeded in winning the attention of Uriel, Tabby’s crush. Tabby’s developing body is a particular magnet for abuse: the students poke her with sharpened pencils, trying to get her to “pop.” When this fails, the pencil-point attacks are replaced by a legion of pointed rumors. “I could normally alchemize other people’s cruel words into flippant jokes I’d learned from fat male comedians,” Tabby says. “Now there were too many new rumors to process.” “According to the hivemind of my classmates,” she continues, “I was a predator who looked at other girls in the locker room, a maniac who wanted to kill Carissa so I could have Uriel for myself, a victim of incest, a product of incest, a slut, a prude, a homophobe.” She knows the source of the problem lies outside herself: “The world couldn’t decide if I was pathetic or a monster or both.” The world can’t decide, but can she?

Every story in Softie draws its drama from something like Tabby’s predicament: relatively mundane interpersonal conflict evokes a much larger, quasi-Darwinian fight for psychological existence. Perhaps that’s why so many of Howell’s characters are teenagers or young adults, often pregnant with or caring for small children of their own. All are“softies,” vulnerable because they’re still developing. Nothing can grow to its right size while trapped inside a small, hard shell, and yet this defensive shell is exactly what characters like Tabby are tempted to develop.

So much energy is absorbed in the fight that true transformations are rare. What occurs, instead, are surreal developments that give a vivid sense of the emergency of thwarted development. There are moments of cannibalism (those earlobes). Several characters chew their nails; one goes so far as to eat her hands. What could all this body horror be about, if not the developing psyche forced back into itself and responding in the same way a starving body, deprived of nourishment, begins to self-digest?

Howell embeds this emergency, of thwarted development, in her compositional choices, her pacing of scenes and handling of time. Occasionally I felt stymied by a story, wanting scenes to move on or appear in a different order. Yet in every case, Howell unerringly evoked the surreal static quality of Dali’s famous clocks, flattened like pancakes and melting over the edges of tables. The stasis reminded me of lockdown time—how all the days seemed the same and endless in their dull terror; and of the peculiar stasis of authoritarianism, what historian Timothy Snyder called, on the eve of the forty-fifth American president’s first term, “flat fascist time,” an allusion to Hitler’s “Thousand-Year Reich,” which lasted only (only!) twelve years but seemed, to those who suffered through it, to go on and on.

Of course, Howell can handle time in orthodox ways. She can do the work of exclusion that readers of contemporary fiction so often seem to require. The collection’s final story, “Age-Defying Bubble Bath with Tri-Shield Technology,” in which a woman experiments with an anti-aging bubble bath that delivers on its promises all too well, is a pacy tour-de-force. But this final story’s furious clip, which matches the lightning speed at which the protagonist devolves, only highlights the collection’s previous moments of emphatic stasis. With her stories Howell reminds readers that the grief of thwarted development can only be lived through; to rush it just deepens the wound.

+++

Megan Howell is a DC-based writer. She earned her MFA in fiction from the University of Maryland in College Park, winning both the Jack Salamanca Thesis Award and the Kwiatek Fellowship. Her work has appeared in McSweeney’s, The Nashville Review and The Establishment, among other publications. Softie: Stories is her first full-length collection.

+++

Diane Josefowicz is books editor at Necessary Fiction and the author, most recently, of Guardians & Saints, a story collection coming later this year from Cornerstone Press.