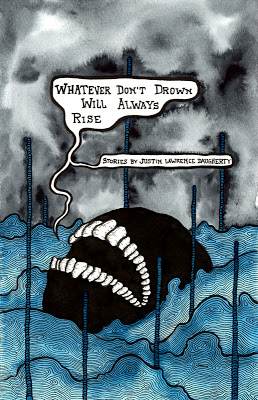

Passenger Side Books, 2013

Drowning is horrific. Water fills the lungs, blood flow is cut off as oxygen stops going to the brain, and desperation consumes the victim. The last seconds of his or her life are a hopeless grasp for air. In Justin Lawrence Daugherty’s collection Whatever Don’t Drown Will Always Rise, drowning becomes a parable for the existential state of being and the search for the next breath is the impetus that drives the characters forward. There are ten short works, inspired by myths, but it’s not immortality at stake. Instead, these pieces are about the tenuously brittle bulwarks people try to make against the impending march of mortality. The events can be supernaturally overwhelming, as in the case of a tornado in “Rebuilding, Construction:”

After the tornado, after the earth ripped up the roots of all our lives, after the howling crushed our daddy, we decided just to bury him there in the backyard. Neely and I brought out the shovels. Other folks all standing around, crying and hands on their faces, their mouths. Doing nothing. Just victimized. But, Neely and I, we dug. We opened up the earth and said our goodbyes and put daddy right back in where we all come from. And it’s after the healing’s done that Neely decided to open up those old wounds.

The imagery is reminiscent of the Biblical plagues, and in many ways, Daugherty is modernizing old myths. In this case, a brother and sister find different ways to cope with their father’s death. Their reaction highlights the differences between “rebuilding” and “construction.” His sister tries to find a way to resurrect their father. The brother finds recluse in construction and tries to form a bond with his sister. Both psyches are frayed, but rather than relying on the trope of dying as the traumatic factor, Daugherty takes us deeper in a conversation between the brother and his uncle who says the ability to resurrect people would vanquish the fear of death:

I said I thought he was wrong, that you’d still be just as afraid, maybe more so. You’d carry the memory of that pain of death with you after coming back. It’s the pain what scares us, I said, not the death.

Pain forms the basis for one of the most original takes on the modern heist story in “Heart Punch.” Taco yearns for his lover, Beverly. Confused by her, he undertakes a scheme to hold up a local diner that becomes his substitute for Communion. Every step of the way, he finds himself ambivalent and his quandary fuses into his torn desire regarding Beverly. He seeks absolution through communication, and unable to find it with Beverly, searches for it with his fellow thieves, wanting to “postpone the robbery and build a fire all three of them could sit around. They would tell their tales and let the fire-smoke carry their words away.”

Daugherty’s stories are short, terse even, and yet the stories plunge readers right smack into the middle of things. Dread packs an introductory wallop, and from there, the characters get deconstructed in a lyrical stream of visceral pain. While tragic circumstances have caused many of the characters to fragment, myths provide solace, however illusionary. In the titular story, “Whatever Don’t Drown Will Always Rise,” two separate sons and fathers search together for the chupacabra, the legendary beast that has never been caught. Dalton, the narrator, realizes that when the second boy asks about the chupacabra, it’s something else he really wants to know:

I know he means his dad, about the track marks on his arms, about the empty cupboards, about yellow fingernails, dried up rivers, broken bones. He wants to know about all the horses that haven’t starved, about trees that have lived for hundreds of years, about animals blind without eyes in the darkest places in the earth, about how we try to kill ourselves over and over but what we really want is the rushing heartbeat of near death, the pumping, the blood.

In essence, he wants to know the mysteries of the universe. Likewise, strange phenomena form the backdrop of the stories, say, as in “Fishkill,” where a pair of lovers drive “past lakes and rivers of dying and dead fish, bodies swelling on the banks and in the sand” or a morbidly disturbing “Suicide Dogs” with a bridge where dogs have committed suicide:

When you’re alone on the suicide dog bridge and no dogs are coming and you just hope that one of them will come running and jump, so you can watch it fall and fall.

What makes the stories so disturbingly alluring is the way Daugherty allegorizes these events to elucidate the broken nature of humanity, a mental hypoxia forced on us from within.

This is not a book about dying, but survival. Story-telling becomes a diving tank, however elusive, for fresh air, providing buoyancy, even a rise from the depths. Safety might be far from the transcendental nirvana that some might hope for. But it’s still better than drowning.

+++

+