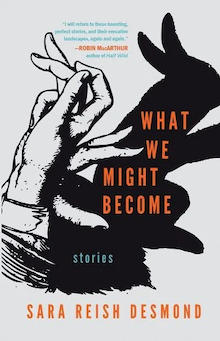

Cornerstone Press, 2024

Change is often imagined as a moment of high drama—a birth or death, a calamity or a great good fortune, a stroke of luck, good or bad. But change rarely happens all at once. More often, change occurs as a series of events, of decisions and revisions, of slow bloomings or strangulations, until you wonder how you got to this new place while seeing, in hindsight, its painful inevitability.

It is these smaller, slower accumulations that make up the stories in What We Might Become, the strange, unpredictable, and excellent collection by Sara Riesh Desmond. Through eleven stories of varied tones, Desmond explores how we become who we are, or how we are going to become who we might be. Characters are at thresholds they may or may not recognize, and their futures are unpredictable.

I say “unpredictable” because, reading these stories, I was never sure what kind of reality the characters were about to face. Some stories are small, sad and, narratively uneventful, but they propelled me along with their shifting points of view.

The first story in the collection unfolds by alternating between a woman who makes clay statues of a miscarried daughter, and an under-achieving middle-schooler and bored Girl Scout who is a disappointment to her parents. Both characters have slight but irreversible dramas. The woman, Elise, tells her son of his almost-sister and then worries that the disclosure has irreparably damaged their relationship. The girl, Cheryl, eats the cookies she sold and should have delivered, and indifferently faces the consequences. When the two characters meet, there is possibility. The girl, about to not apologize for eating the cookies, askes Elise, “What kind of girl do you think I am?” Explaining that she ate the cookies and doesn’t care, she asks “What do you expect of me?” The narrator continues:

As the girl explains herself, Elise cannot know whether this encounter, this young girl sitting comfortably in her kitchen wiping at her bold mouth with the back of her hand as she bares some part of herself to a stranger, is coincidence or a calibrated response to Elise’s own quiet sorrow.

This moment could be revelatory. The lost daughter could find herself in the mother who actually sees the possibilities in the girl’s stunted life. But that’s not the way it goes. Nothing actually comes of their meeting—and yet, Desmond gives the sense that the encounter might still alter them both, even if only slightly. It might be a bit of a redirection from their altered trajectories. As with so much in life, their interaction could be crucial or it might barely be remembered. But it happened. It did—and everything that happens in a life can change it, even if only slightly. Desmond is keen to understand how this change happens while remaining sensitive enough not to draw conclusions from her characters’ uncertain trajectories.

These trajectories more often than not happen in small towns, in exurbs and beyond, not quite rural, but places where cars break down and dreams become dusty. These are not places stricken by poverty, but by distance from possibility. They are where becoming becomes less romantic.

Another story, “Up Dell Drive,” might be this ethos in sum. The story unfolds slowly. Honey, a teenage cashier at a grocery store, interacts with her neighbor, an Iraqi woman who brings food and books to Honey’s father, bedridden from the wars against Muslims in Iraq. Honey works with Antonio, a handsome El Salvadorean coworker from her high school who goes by Tuna.

Honey and Tuna, sneaking out back of work, talk while he gets high. Honey talks about her wounded dad; Tuna shares his ambition to enlist in order to have a better life. One thing leads to the other, and they start to make out. She “tries to kiss him like she’s admired in movies, better than anyone she’s kissed before, tries to make her kiss into one that would make him forget she’s white.” But more happens, and they start to fuck, and she pulls away.

He’s not at all put out; it’s not that kind of story. But she is. She tries to explain. “‘I gotta go. My Mom’s waiting for me,’ Honey says, conscious of the way this excuse will sound in her own head later on, maybe even for years to come.” In other words, Honey feels that she’s becoming something. She thinks she sees what her inaction will do to her, how it will live in her, haunt her. But that’s not even how the story ends. There is still aching father-daughter stuff to come, as Honey tries to reconcile her loving father with the man who came back broken from fighting in pointless imperial wars.

There are of course important points to all of this — the immigrant who wants to fight for a country we know fears him, the Muslim woman slyly helping the man who both killed and resents her kin — but that’s not what is important for Honey. Or rather it is, but in ways she only sort of understands. And that’s what makes Desmond’s stories so real, so painfully true.

To be clear, not all her stories are to-the-bone realism, though they are no less resonant for their artifices. One, “The Dwindling,” is of extremely-real artificial/cyborg children who seem to be dying unexpectedly at a certain age, in a way that the science that created them said couldn’t happen. Mother and (fake? real?) daughter who are both dealing with that upcoming reality. While the premise sounds like any speculative fiction, the story is decidedly Desmond. Tragedies barreling toward the characters are desperately minimized. Small but important signs are dissonanced away. It feels like how America faced mass death. It feels like how people find communities to rationalize their fear. There’s nothing synthetic about that.

Perhaps the most difficult story, and the one that has stuck with me, is “The Fells.” In this story, a woman, dealing with difficult life changes, walks her dog in the woods. She is followed by a man who is friendly but also somewhat menacing, whom she has seen around with his dogs. The man is not kind. He says weird rude things about women. He acts like he knows her. And the hell of it is their dogs keep playing and she can’t get away.

Small moments. Small decisions. What she eventually does is stomach-churning, and you know it will impact her the rest of her life, however she maybe-probably-reasonably justifies it. But she’ll never be the same.

The urge to pretend that nothing is happening, whether in moments of panic or in moments of vague existential uncertainty, is universal. We never want to think about what might actually come next. Desmond’s book says that these moments matter. That there is something happening. Things are always happening. We are, in fact, always becoming.

+++

Sara Reish Desmond‘s work has appeared in The Kenyon Review, The Los Angeles Review, and Water Stone Review, among other journals. Her short stories have been finalists for the Rick DeMarinis Short Story Award and the Copper Nickel Award. She teaches and writes just north of Boston, where she lives with her husband and two daughters.

+

Brian O’Neill is a freelance writer in Chicago. He is a reviewer specializing in small presses, novels in translation, foreign policy, the Midwest, and regional histories, and he also writes about baseball. Follow him @brianoneill.bsky.social on Bluesky.