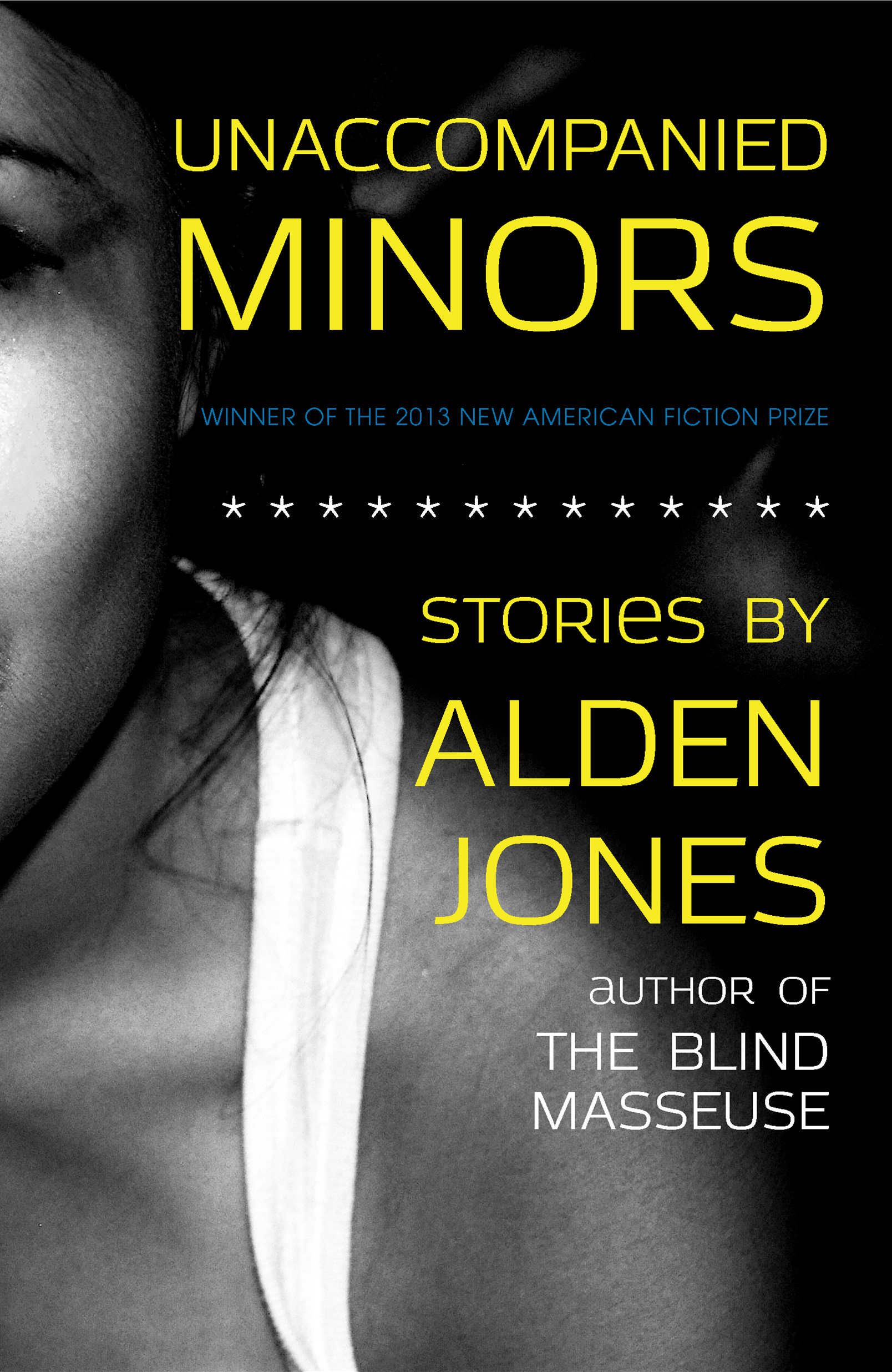

New American Press, 2013

In her debut short story collection, Alden Jones offers a frank glimpse at the country club youth lost to the economic privilege of contemporary America. With the exception of the Costa Rican hotel worker in her story “Sin Alley,” Jones’s central characters are products of middle class to wealthy upbringings from suburban environments along the eastern seaboard, from Florida to New York. These youth seem to have everything they could want except genuine affection, and we witness the jaded cynicism that springs up in the gap where love might have been.

The collection offers a number of characters facing various traumas, including the deaths of friends, lovers, and children, both their own and those whose care they oversee. John Donne once wrote that “any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind,” but the minors in this collection feel no such sympathy. As the speaker in her final story, “Flee,” says, “It was something about human frailty that pierced us more than the idea of losing Ryan himself.” In terms of human sentiment, they are already far too diminished to feel much besides self-pity at the loss of other human beings. The unaccompanied minors here are poised at an age at which they at least might mourn their own childhood, but neither this nor the deaths around them prompts much response other than increasing weariness with an American culture that so warps and corrupts human sympathy.

Jones possesses an astonishing skill for creating characters and settings that feel fully realized from the first line to the last. Their voices carry the stories forward, implanting us in their disorienting perspectives of familiar landscapes. Take, for instance, the first lines of the collection: “We’re in a homeless shelter in Asheville, NC. We think it’s funny. How did all these people in some hellish hickish place like Asheville, NC, get homeless, that’s what we want to know.” Jones splices her comma here so that the question of homelessness is transformed instead to a statement of ignorance. The speaker privileges her own perspective, her judgment of the place as hellish and hickish, and her callus statement that being in a shelter is funny, over any acknowledgement of the suffering of others. In three short sentences, we are fully ensnared into this girl’s disturbing view of a world we recognize only too well, and we can’t help but wonder what kind of future awaits those who see the world with such cruel eyes.

What makes Jones’s collection’s critique of privilege all the more thought-provoking is that Jones includes herself within it. Her story “Heathens,” which occupies the literal and figurative center of her book, relates the story of a gringa teacher, Lana, who lives among American missionaries and native Costa Ricans—a position Jones herself once held. The story’s first person point of view combined with a direct address to the character of a young missionary, Molly, establishes an I/you dynamic in the voice that seems to implicate the writer and reader in those pronouns. The teacher’s love of her pens and paper and her penchant for manipulating Molly into situations that will ask her to challenge her American values both seem to reinforce the implication that she stands in for the writer.

Yet we soon realize that Lana’s views of her world are as problematic as Molly’s. Having lived in Costa Rica for a year, she disparages American turistas, whom she sees as wholly separate from and inferior to herself. “I hated the way they giggled,” she says. “I hated the way they wanted boys around but squirmed when they were. I wanted to see one of them cry. I wanted evidence that just one of them was familiar with pain.”

When Lana learns that one of her seven-year old students sees her as a gringa and, thus, an outsider as well, Lana is, in her own words, “outraged.” Lana would like to be completely divorced from the country and culture that created her. Yet as readers, we are aware of how much closer she is to those she mocks than she is to those whom she seeks to help. Indeed, within pages, she describes her Costa Rican neighbors as being “so much like dogs,” a repulsive sentiment that shows just how deeply her sense of superiority is ingrained.

Though I doubt Jones would agree with the ugly thoughts we see rising in Lana, by aligning Lana with her own position as writer, Jones raises questions about her own stance as she does her protagonist’s, suggesting that even seemingly good motives, such as the desire to help the less fortunate, are corrupted by a privileged upbringing. Like Lana, Jones may feel removed from the neo-Conservative, American wealth, but that sense of distance is not enough to extricate or exonerate her. It’s a tricky stance to maintain, but what separates Jones from her characters is her sincere attempt to accomplish exactly the act that seems most difficult in this collection: extending sympathy.

Unaccompanied Minors is by no means light entertainment, exposing as it does the ugliness that festers in our suburbs, but both the quality of the writing and the shrewdness of the questions she raises make this collection a worthy read.

+++

+