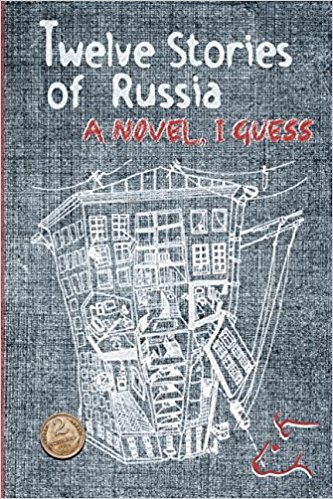

Cow Eye Press, 2017

The title of A.J. Perry’s first book, Twelve Stories of Russia: A Novel, I Guess, presents the reader with an ambiguity. The novel, if that’s what it should be called, is narrated by a young American named James who, after reading an ad in the newspaper, moves to Moscow in the early 1990s to teach English. The short way to resolve the ambiguity posed by the title is to say that some of it very well could have happened, and some of it very likely didn’t (stories of feral bears roaming the streets of Moscow, for example, tend to be apocryphal).

The longer way will take some explaining. One of the first things the reader will notice is the playfulness and experimentation of Perry’s style. Smaller stories are told within larger ones, resembling the structure of a Russian nesting doll. Certain details (the progressive decline of the ruble, grammar mistakes presumably made by James’s Russian students and friends) recur throughout, in very brief sections:

The ruble continues to fall (1USD=150RUR). By now the monthly salary of a tax inspector is less than the price of a carton of Marlboros.

————————

…and falls (1USD=820RUR)…

————————

Wrong: We are making love with you.

Right: You and I are having sex.

Perry seems to be reminding the reader that time passes on a number of different tracks. The references to the decline of the ruble, on one hand, suggest the global fluctuations that exist in the background of an individual life, and sometimes influence it greatly: exchange rates, the success or failure of societal reforms, etc. The references to grammar, on the other hand, seem to take place outside of narrative time; they give a sense of the linguistic texture of James’s experience, and often hint at certain aspects of the story that are not stated explicitly. It becomes clear that Perry is concerned less with telling a traditional story than capturing the sensations of everyday life in a particular time and place.

James and his Russian friends talk—about the proper way to drink vodka, race relations in America, Anna Karenina, Gorbachev, and about dusha, the concept of the “Russian Soul.” There is a seemingly intentional (and sometimes frustrating) lack of substance to many of these conversations, focused more on wordplay than content—almost as if the author is winking at the reader and suggesting that none of it really matters, that it’s all a cliché. James’s friend, Vadim, explains:

Just think … you could write about your experiences here … about how you came to Moscow and everything was strange and scary … blah blah blah … you know, the usual bit: poor sensitive foreigner lands in Moscow expecting poetry and black bears but instead … bread lines … toilet paper shortages … people yelling and shouting … I’m telling you people would buy it up…

And after James protests that none of that is exactly true to his experience:

That’s not the point … the important thing is that it could’ve happened. You see? And besides, if you think people will remember … well okay there will be people who nit-pick about the dates, but in general no one will remember … I mean five years from now do you think anyone will care whether something happened in this year or the next? Do you think they’ll care about whether it even happened at all? Of course not!

Ironically, when the reader is introduced to Vadim and his girlfriend, Olga, Twelve Stories becomes an interesting and believable novel. Through Vadim’s story, which James relates with an attention to nuance and sympathy that he doesn’t afford many others, the reader learns how seemingly easy it was to start out as an entrepreneur in the “wild, wild west” of Russia’s early ’90s, and also how easy it was to lose everything and end up owing money to the kinds of people who remind you of your debt by calling in the middle of the night and just breathing into the phone. James’s relationship with both Vadim and Olga unfolds in subtle and fascinating ways; the two of them take over the second half of the book, and it’s the better for it. The lack of exposition becomes a strength, the experimentation lessens, and there is so much dialogue (some of it funny, some of it sad, most of it vodka-inflected) that the reader begins to feel a genuine intimacy with these characters.

Throughout the book, James makes it clear that he is looking for something. Sometimes it seems to be a response to the koan-like phrase, “that which changes and is changed, and is hopelessly beyond your reach;” sometimes it is the nebulous idea of dusha. Whether one believes that there is such a thing as a distinctive “Russian Soul” or not, perhaps there is some equivalent idea for anyone who travels to a foreign country with a spirit of openness and stays for more than a couple of weeks. You don’t want to leave until you understand, and can tell others what you’ve understood. But just as A.J. Perry is reluctant to call this a novel, his narrator is reluctant to lay claim to great wisdom that may seem to be the province of novelists. As James notes towards the end of the book, maybe it is most honest to admit that understanding—due to the barriers of culture, language or history—is beyond our reach:

But maybe…it’s better that way? Maybe there’s something to be said for wanting and dreaming? And for having something to elude you? Maybe I am happier for not having found it. Richer for not diminishing its beauty by claiming to understand.

In other words, undiluted experience may speak more clearly than the pretense of wisdom. Perry’s book is most successful when he brings that experience to life.

+++

A.J. Perry’s Twelve Stories of Russia: A Novel, I Guess was originally published in Moscow by the independent publisher GLAS (2001), where it quietly gained a following among expats and locals alike. He is also the author of Douze histoires cul sec: Un roman, je presume (Editions Intervalles, 2006) and The Old People (Thames River Press, 2014).

+

Michael Keane is a writer who lives in New Jersey. He is currently working on a book of essays.