Coffee House Press, 2025

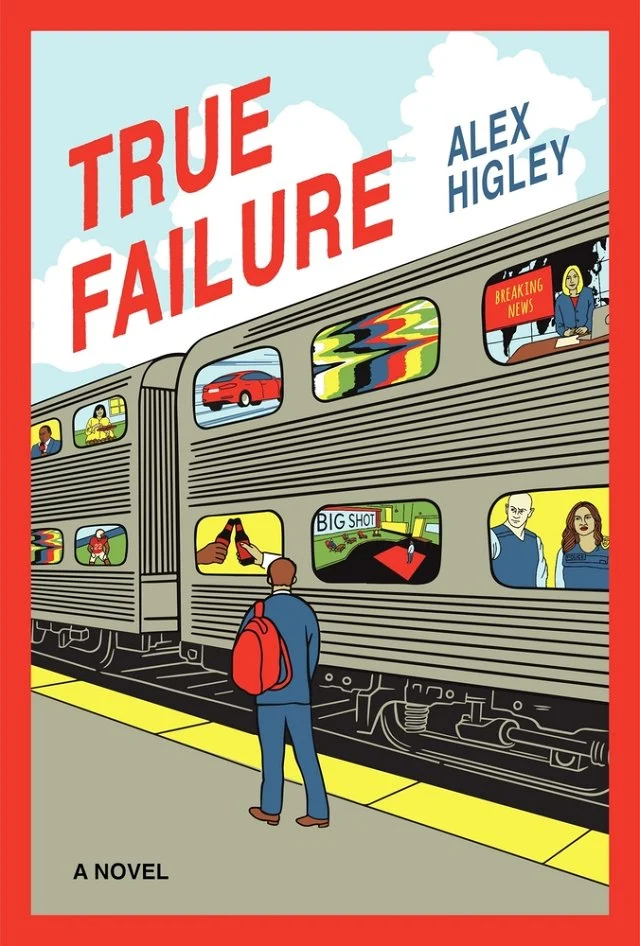

In Alex Higley’s True Failure, if the American Dream survives anywhere, it’s in the realm of reality TV, where shrewd producers create a social microcosm in which small windfalls come to those bold enough to compete for them. True Failure centers on the fictitious Big Shot, a Shark Tank-esque production where aspiring contestants pitch business ideas to a panel of investors. Higley’s novel follows a small cast of characters comprising a wannabe contestant, Ben; his wife, Tara; and three members of Big Shot’s production team, Marcy, Callie, and Brent. Their connections span half the continent, from Chicago to LA, encompassing a web of American liars and American lies.

The novel opens with Ben getting fired from his accounting job. He resolves to lie about it to his wife, Tara: “He would lie, then continue to lie and deceive to perpetuate his original lie of not telling her he had lost his job. He didn’t want to lie to her, but the alternative, honesty, did not occur to him.” What occurs to him instead is going on Big Shot. To Ben it seems like a good way to avoid the grim bureaucratic realities of unemployment as well as greater honesty with his wife. From the first page, Ben is dully enmeshed in deception, making decisions that support his avoidance of reality.

Having no business or invention to pitch, Ben instead brainstorms about the person who would most appeal to investors and TV viewers. “Mariska Hargitay,” he writes in his notebook, “attacked”—a cryptic reference to a beautiful, powerful woman who has been subjected to sexual violence. The decision to record this thought—a projection, perhaps, of Ben’s understanding of himself as a victim—proves fateful, as Ben’s notebook falls into the hands of the show’s producer, Marcy.

Overcome by existential ennui, and buoyed by the same current of passive deception that carries all of True Failure, Marcy makes a half-hearted bid to leave Big Shot by pretending to her coworkers that she’s departing on a Canadian vacation, when in reality she’s merely heading off to an apartment elsewhere in LA. Rather than face down this time alone, she invites along a woman who won’t stop calling Big Shot’s casting office, begging them not to let her husband on the show. And so Ben’s wife Tara ends up selling Ben’s notebook, with its bizarre, salacious Mariska Hargitay reference, to Marcy. In this roundabout way, Ben’s TV ambitions do end up making a dent in the couple’s debt.

The novel’s characters behave irrationally, yet they are loyal to their own rationalities. Ben dresses for work every day post-firing and heads to the library to binge SVU. Tara dutifully records false observations about the children she watches in her home daycare, creating diaries that will eventually be passed on to the kids’ parents. Marcy hires her taxi driver to bring eggs to her vacation apartment, in order to make her fake life seem lived-in. Marcy’s intern, Callie, invents her reports to Marcy instead of conducting actual research.

Higley exposes modern America as a place in which such nonsense is undergirded, reified, by routine. Though Ben is threatened with being revealed—to his wife, to Big Shot investors, and to spectral but limitless spectators—as a “failure,” a person with no original thoughts besides the crude and obscene, this threat is ultimately an irrelevancy. Life goes on, as it routinely does; another contestant steps up to the plate. The couple still watches Big Shot: “There were no hard feelings, really.”

Higley’s sentences unfold in unusual ways that reflect the “submerged quality” of Ben’s personality and speak to the dulled confusion in which all of these characters operate. Yet moments of beauty do emerge from this jumbled landscape. Despite their debts and deceptions, Ben and Tara are nonetheless a loving couple who look forward to expanding their family by the novel’s end. As Tara contemplates her pregnancy, she imagines the better future it offers for her and Ben: “She wanted their life to become daily: for them to live inside the days together and stop projecting hopes and losses outward in all directions. Fail and cry together; wake up and do it again.” The central failure at the heart of True Failure is the failure to live groundedly, without projection. Ben’s ingrained habit of projection is a character flaw, a result of the perception that lies can become truth in the same way television has become his reality.

True Failure is delightfully—and sometimes frustratingly—bizarre, its humorous touch light but present enough to establish that Higley isn’t laughing at his characters, fumbling and self-destructive as they might be. With an ultimately empathetic spirit, Higley crafts a world that feels at once familiar and uncanny. The effect is reminiscent of watching a reality show featuring recognizable characters who are just slightly too peculiar to be real.

+++

Alex Higley is the author of Cardinal (nominated for the PEN/Bingham Award) and Old Open. He is a founding editor of Great Place Books. Raised in Colorado, he currently lives southwest of Chicago.

+

Grace Novarr is a recent graduate of Barnard College, where she edited the Columbia Journal of Literary Criticism. She lives in Brooklyn and works as an assistant at a literary agency.