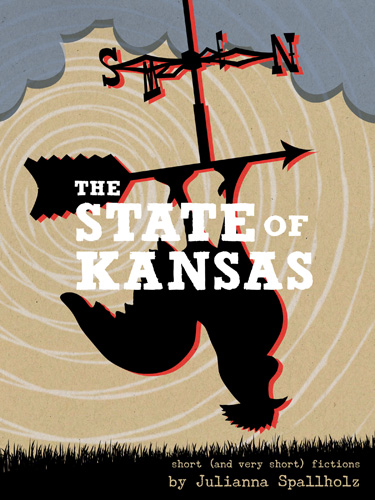

GenPop Books, 2012

Flash fiction sits on a continuum between poetry and traditional narrative. Its only defining characteristic is its brevity. With no real minimum word count and a maximum hovering somewhere around 1000 words, flash fiction is about eliciting an instantaneous connection, a reaction, between the reader and an idea or image or feeling contained in each short piece. It is about the ability of a few words to hint at or reveal a much bigger story. It is about designing a powerful image or inciting a resonant emotion. It is often about catching the reader by surprise.

A collection of flash fiction is an interesting body of work to consider as a whole. Unless specifically connected, each piece must stand on its own. Must create that flash of heat and light, that lightning bolt charge between the reader and the piece. In this way, flash fiction is a more difficult form than its longer cousin, simply because it doesn’t have the leisure of multiple scenes or voice-driven explanation or layers of detail to lure a reader into the collusion needed to make a fictional world come alive.

Julianna Spallholz’s collection of short and (mostly) very short fictions, The State of Kansas, is filled with many a lightning bolt, moments when her careful assembly of only a few words quite literally shocks, burns, scratches, and dazzles. There are pieces here—miniature worlds wrought of startling images and unsettling voices —that will echo long after a reader has finished and moved on.

Take, for example, “Portrait,” which opens with a description of the narrator’s grandmother’s home, and of a painting that hangs in the front hall. In one short paragraph, Spallholz cleverly moves from an expressionless and objective description to a subjective and stuttered avowal of both bravery and fear:

The front hall had a long dark red carpet and heavy oak furniture and on the wall was a huge portrait in a heavy frame. It was of a large man with a black beard and black robes holding a black book, his right hand raised. I believed that the man was God and I was small and would walk carefully past Him. Sometimes after dinner I would challenge myself to enter the front hall alone, to tiptoe, trembling, to stand in front of God, to look at Him, to keep standing, to keep looking, to stand looking, unafraid, at God.

The longest of Spallholz’s mini-fictions, placed directly or almost directly at the center of the book, is, without a doubt, the most powerful of the entire collection. Both enigmatic and surreal, “Thanksgiving” tells of a holiday dinner party, it tells of want and of feast and of famine. Of devotion and self-denial, of oppression, of the desire for transgression, for freedom.

This particular piece also highlights Spallholz’s talent for rhythm and repetition; the story has a strong beat, a driving pulse. Here is our starving narrator, contemplating a piece of pie:

(No. I wanted to use my hands. I wanted to reach into the center of the pie, to the good part, the indelicate part, I wanted to reach into the heart of the pie, to pierce through the outer beautiful skein, to get to the center of it, the nucleus, the wetness, I wanted to touch what made it what it really was, and I wanted to grab it, make a fist, put it in my mouth, and I wanted to use my teeth to chew it, I wanted to use my tongue, I wanted to taste it, to feel it, to wreck it, to make it mine, and I wanted, I wanted, to swallow. ((I wanted for you to see me do it. I wanted for you to see me. I wanted, I confess it (((the shame, the sorrow))) I wanted, for a moment, to make you suffer.))) (I wanted to defy you.)

(I wanted to not disappear.)

Despite the strength of most of Spallholz’s tiny fictions, including many exceptional pieces like: “Woods,” “Recess,” “Home,” “Portrait,” “The Body,” and “Who Will Take the Cat, ” the collection has a few weaker pieces, moments when a story hints at but ultimately fails to generate an electrical storm. For me, this comes from the particularly minimalist narrative style that Spallholz favors. Here, for example, is “The Dog:”

She takes the Labrador retriever to the park in the late evening. She and the Labrador retriever enter the park. She hears a highpitched whistling screaming sound. She also hears cheering. She looks up the hill in the park. There is a cluster of men standing near a tree. There is a dog hanging by its mouth from a limb of the tree. The dog is a pit bull terrier. The pit bull terrier is clenching the limb of the tree in its mouth. The pit bull terrier is screaming. The men are cheering. The pit bull terrier will not let go of the limb of the tree until the men tell it to let go. The men will not tell it to let go. She is afraid of the men and she is afraid of the pit bull terrier. The pit bull terrier will defend the men who will not tell it to let go. She and the Labrador retriever leave the park.

The deadpan, almost monotone narrator works in the beginning to create a fantastic feeling of menace and foreboding, but that very distance works against the story in the last line. This happens in a few other stories, but mostly Spallholz uses her distanced narrator to great effect, knowing when to release the distance and offer an uncomfortable truth, or knowing when to use this kind of minimalism to focus on exactly the right detail, a detail which then transforms the meaning or the emotional current of the piece in question.

With its forty-three short and very short fictions, The State of Kansas is a fine but brief offering of the range and depth of Spallholz’s writing and leaves us looking forward to her future work.

+++

+