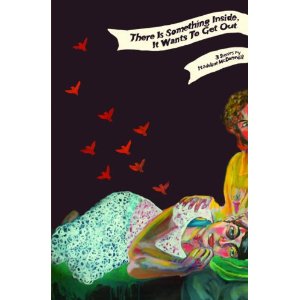

Rescue Press, 2010

This engaging trio of stories by Brown undergrad/Iowa MFA writer Madeline McDonnell are deceptively rewarding. Although they are not three parts of a greater whole, they are related in their themes, by certain metaphors and constraints, and by their accomplished style. Shot through with humor, each seemingly simple story proves, by contrast, its true depth. Madeline McDonnell is wise, accomplished and confident with a quick turn of phrase, and equally, with bigger issues of real importance. Her characters are in turn aching, tolerating, and growing, and then in fluttering, elusive moments, ultimately, achieving something akin to success. More than simple survival… the young women in each of these stories border on the possibility of arrival.

The first story, “Wife,” details a reluctant fiancée’s “yes” to Ben the historian’s proposal in a Spanish café, and her ensuing trouble telling her marriage-averse mother. It becomes clear that the young woman, Wednesday, may not despise the marriage like her mother does, but she’s certainly conflicted about her feelings for her future husband.

He wore khakis, as he did every day. Wednesday watched him fiddle in his pocket and thought of the pressed row of them in his New York closet. That toneless, heartbreaking row. She was filled suddenly with love for him, or with that thing she was wont to be filled with, that thing she mistook for love.

Later, Wednesday excuses Ben’s fastidious, monochrome nature, blaming his upbringing, just as she understands her own idiosyncrasies—her very name, for example—as the fault of her own parents. The narrator tells us that, “His parents, too, leave pinstriped messages on the voicemail.”

What a line! Is Madeline McDonnell a writer to fall in love with or what? One can hardly blame Ben for falling in love with Wednesday, and wanting to marry her—even if the reader sees a more clear picture than Ben might.

“Did you come?” he asks. (“Did I take out the garbage?”), and Wednesday says, “Yes.” It is always easier to say yes. It is easier than the truth. The truth is complicated, it defies language. It is the sounds that fly from her like confused, contrary birds.

And there it is—the bird, the word, the moth, the errant sound, or flying thing that escapes in all these stories, or tries to, or tries desperately to remain suppressed. Entirely organic and subtle, McDonnell’s clever use of this flight-metaphor, among many others, creates something fresh and unique.

In the second story, “Physical Education,” a teenage cancer survivor, Mary, is alternately encouraged and humiliated by her father coaching her basketball team at school. The family has sworn off all possible carcinogens, including deodorant, which means Mary’s sweaty father’s inevitable role on the team—not just as coach—is all the more repugnant to her. Her radiation treatments cause relentless nausea and the only thing she can eat is a highly processed cookie, which she allows to melt to “elf-spawn” in her mouth. Mary’s father’s efforts on the basketball court are both heartbreaking and disgusting, as he seems to value the game more than his daughter’s recovery and sense of self. Still, the reader can’t blame him. He’s found a way, however oblique, to lighten the load cancer has brought on his family, and to redirect their focus just a little. This story, despite its darkness, is also very funny and light—something only a very skillful writer can accomplish. Madeline McDonnell makes it look easy.

The third story, “Trouble,” is another revealing view of a young woman’s presumably ordinary domestic situation—a new pregnancy. Lucy Burke now faces her unresolved feelings about a long-ago affair with her high school basketball coach, and the resultant pregnancy and abortion. Today, she shuts her eyes (literally, emphatically) to the fact of her new pregnancy against the backdrop of the surfacing memories. Her husband Henry (ironically bearing the same as her basketball coach’s last name) knows nothing of his wife’s trauma, and he cannot understand her dangerous emotional instability, nor the way she keeps crashing the car. Less humorous than the other two stories, this one still has plenty to say, and the voice is just as powerful.

All three pieces in this collection are lovely stories of navigating the agonies of growth and finding the absurd and humorous throughout each journey. American fiction (even literary fiction brought out by independent publishers!) may be accused of requiring a happy ending—neatly tied in a metaphorical bow. A hard story, well-told, with a soft landing at the journey’s end is often de rigueur. But there is nothing trite or easy in these story or character arcs—even when a final line delivers beautiful shimmers of hope.

+++

Madeline McDonnell is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and a former lexicographer for the Oxford English Dictionary. She lives in Seattle, where she is at work on a novel and a longer collection of short stories.

+

Nancy Freund is an American-British novelist and poet with a B.A. in English/Creative Writing and an M.Ed. from UCLA. In addition to writing and teaching, she’s been in editing, publishing, book marketing and publicity. Involved with the University of Iowa Summer Writing Festival, London’s Women in Publishing and the Geneva Writers’ Group, she currently lives in Switzerland.