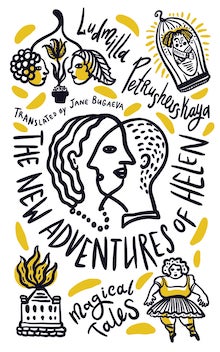

translated by Jane Bugaeva

Deep Vellum, 2021

I used to think fairy tales were only for kids — classics adapted by Disney, fantastical stuff used to lull children to sleep. But I’ve been reading fairy tales all wrong. They’re not just simple stories with a “happily ever after.” Operating in the safe space of “once upon a time,” they give us a way to think and talk about difficulties and uncertainties. Ludmilla Petrushevskaya’s collection of magical tales, The New Adventures of Helen, reminds us that we can add to that repertoire of fantasy well into adulthood.

Originally, fairy tales were told in communal settings. Imagine people gathered by a fire, comforted by the stories shared around its blaze. Like that fire, stories shine a light in the dark. In The Fairest of Them All: Snow White and 21 Tales of Mothers and Daughters (2021), the folklorist Maria Tatar asks: “What do you do when faced with worst-case possible scenarios? What do you need to survive cruelty, abandonment, and assault? In fairy tales, the answer often comes in the form of wits, intelligence, and resourcefulness on the one hand, and courage on the other.” Such tales have staying power. These are stories that we keep with us.

Faced with the worst, Petrushevskaya’s characters rely on compassion and collaboration. In “The Story of an Artist,” a poor artist swindled out of his apartment finds joy in the tiny footprints of children that muddy up his street art. Later, he discovers a magical canvas and realizes the subjects of his paintings fade from existence after they are painted. While he is “secretly proud that only his paintings were able to preserve that magical light,” he eventually learns to paint only abstracts — never people or landscapes. The tale itself works rather like a magical canvas, preserving that same “magical light” by infusing elements of charm and humor into a story of poverty, shame and ridicule.

Petrushevskaya’s collection also allows us to think more critically about how to act in a crisis, how to be quick-witted and ingenious. In “The Prince with Gold Hair,” a queen and a prince are ejected from the kingdom. They survive due to the queen’s resourcefulness — her ability to devise their escape from prison using strands of her son’s gold hair as bait, her decision to join the circus to earn a living, her ability to locate her parents. All the while, they are followed by an enchanted star that proves the key to their rescue. They later reunite with the king and form their own kingdom: “Simply put, they sold their yacht and bought an apartment in the suburbs.” With wit and irony Petrushevskaya charms her readers into reimagining a faraway kingdom in the house next door.

Petrushevskaya’s heroines take on challenges with courage. In “Two Sisters,” we find Lisa and Rita, elderly siblings, suddenly transformed into their ten- and twelve-year-old selves: “The day of their transformation, the girls reassured each other that everything was fine: they were young, they were smart, and they could look after themselves.” They figure out how to get their pensions from the mailman and sew themselves new clothes, eventually moving in with and taking care of an old friend. With this tale as with the others, Petrushevskaya suggests that there’s practical wisdom to be drawn from folklore as well as breathtaking insight.

In the book’s titular story, Helen of Troy is reborn when a wizard fashions out a mirror for her. This magical mirror causes the person viewing his or her reflection to disappear “without going anywhere.” In other words, no one notices you anymore. Paradoxically, vanity leads to invisibility. The breaking of the mirror’s glass, however, makes that person visible again. Helen uses the mirror trick to cause her billionaire love interest to “disappear” so they can enjoy a life out of the spotlight. “Maybe they’ll smash the mirror and reappear one day,” Petrushevsakaya writes whimsically. Rewriting the story of Helen of Troy revives her for a new audience and reexamines conceptions of beauty.

Perhaps Petrushevskaya is the best person to write fairy tales because she has lived one. Her memoir, The Girl from the Metropol Hotel: Growing Up in Communist Russia (2017) is about her coming-of-age as an “enemy of the people.” Born into an elite family of Bolshevik intellectuals in 1938, she grew up at the resplendent Metropol Hotel in Moscow; in the wake of the Russian Revolution, she was separated from her mother for four years and went through other people’s trash to survive. Although her books and stage plays were often censored by the Soviet government, she now wins literary prizes and has become one of Russia’s most beloved writers. She embodies resilience. She gives voice to survivors.

In these tales, Petrushevskaya is bent on understanding why things go wrong, which is far more interesting than focusing on what goes right. The stories can be appalling, traumatic, even absurd, yet they have a deceptive lightness and simplicity, and they evoke a feeling of adventure. How Petrushevskaya manages to achieve that remains a mystery that must be part of the magic.

+++

+

+