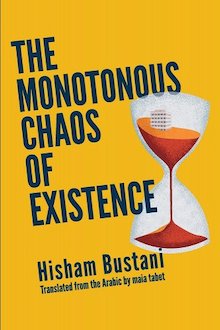

Translated by maia tabet

Mason Jar Press, 2022

Rendered into Western literature, monotony is usually the afflicting boredom of the unafflicted: the daily punch-in-punch-out; mewling kids needing to be fed and un-mussed; long lines in the post office, dust dancing through late afternoon sunbeams. It’s assumed as a matter of convention that chaos is roiling underneath.

But what if chaos is on the outside? What if life is punctuated by war, by political oppression, by occupation, by the shackles of history and the mutations of poverty? Can that be, well, boring? This is one of the many questions asked by the Jordanian writer Hisham Bustani, in his dizzying, ferocious, genre-defying The Monotonous Chaos of Existence.

Bustani, one of Jordan’s most important modern writers and activists, has created a swirl — part surreal novel, part comedy, part prose poem, part history lesson. He blends historical realism (including photos of real people, famous and not, in a “Museum of Found Objects”) with self-consciously off-putting surrealism to conjure something new and unique, a visceral and tangible exploration of lives subsumed in the fire of war or the gray bureaucracy of stultifying and sclerotic regimes.

There is also love, and sex, but more of that in a moment.

Divided into three sections, the book unfolds as a collection of short stories, though even saying that is to assign a category to what is essentially uncategorizable. The first section, “Disturbance,” mostly takes place in Amman, both real and as a dreamscape. Anyone who has spent time in the Arab world, especially Amman, recognizes the sprawl, the poverty, the beauty surrounded by weeds, diesel fumes, and the rattling clang of a thousand service stations.

In Bustani’s tales, intellectuals have surreal arguments, monologues from The Matrix and conversations with Carl Sagan mingle with a street-yeller’s agony, real historical characters filter in and out, and couples get trapped deep underground, in the sewers, while watching TV. Bustani’s stories are weird, slippery, and hard to grasp, but the emotive truth is that lives are slipping away, lost inside a system of rules that someone or something else conjured up far away, without regard for individual lives.

Perhaps the starkest example of this is “Faysali and Wehdat.” The two names refer to two soccer teams in Jordan. The first is made up of East Bank Jordanians, or Jordanian Jordanians, while the second, of Palestinian Jordanians, who technically have a state but suffer discrimination in their non-country. These teams are rivals, and the hatred between the fans spills into their daily lives. But the hideous irony is that their division stems from a made-up line.

There were no Jordanian Jordanians; there were no Palestinian Jordanians; the distinction arose following the world wars of the twentieth century, when the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire opened that part of the world to the backroom map-making of Western imperialist interests. In Bustani’s story, personifications of each side — the Green Man and the Blue Man — kill each other and themselves, leaving behind a single beaten and sliced-up body. It’s surreal political body horror worthy of Gombrowicz.

No punches are pulled for Israel, as most of the Gaza section takes place during the horrors of Israel’s 2008-09 crackdown. Indeed, one of the stories is a time-bending and bloody recounting of the history of the occupation filtered through Bustani himself. A series of grim and gruesome images, which have the brutal and uncaring placidity of nature, underscores the thrumming inevitability of unpredictable death in this place: “The sea is calm. Below the surface, shoals of fish glide among the multi-color coral. Above, the metal-gray warship fires its load on bands of children, leaving them swimming in water the color of blood.”

With all this violence, how can life be monotonous? It seems contradictory — but it isn’t, as Bustani makes clear. The worst part of monotony is that life can slip away: whole days are lost waiting at checkpoints and dealing with a government that actively despises you. In between, people try to do ordinary things — find work, get laid, engage in endless arguments about the nature of life. And what does life give? Bustani answers that in “Paper on Table Next to Overturned Chair”:

Now, after all that’s happened, I acknowledge that we are condemned to life; I have to recognize that not only are we not free in choosing freedom, as some would have us believe — even though I’ve always thought that was an oxymoron — but we are also not free in that we have no choice in the matter of being born.

‘This is what my father inflicted on me.’

So what is left? The last section of the book, which contains an erotic and funny graphic novel, is surprisingly romantic and sexy, if not exactly hopeful. It feels like breaking free, even for the space of a song or a sigh or a spoken word or just a spasm. Finding a moment to live between the chaos and monotony is never easy but as Bustani shows, it might be worth it.

+++

+

+