Curbside Splendor, 2013

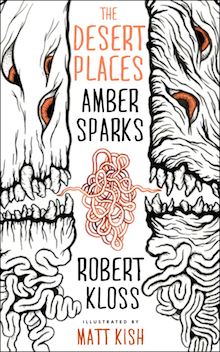

Despite its brevity (86 pages), Amber Sparks and Robert Kloss’s The Desert Places should be mulled over slowly, deliberately, and preferably, if one is squeamish, in well-lit places, for this hybrid text of lyrical rhapsodies, interrogatives, lists, Q&As, omniscient pronouncements, lexicographic glossaries, lush vignettes, and gruesome full-color Matt Kish illustrations is an extended meditation on the nature of Evil and, through indirection, readers are left thinking of the nature of man.

The prose is powerful, striking, at times approaching the pitch of Melville and the King James Bible. Consider this account of Evil’s creation at the beginning of the world:

Who were you when the first breath of heaven burst forth? When all the light and matter and moments blazed from nothing? When fires scorched the firmament and all was shrouded in dust?… You were a negative, a dark absence, a clump of cells crying to come together. You were a pause in the flickering before consciousness. And when the atoms swirled, and when the skies yawned, and when a nervous god, still virgin to creation, called you forth: did you marvel at your luck?… Did you grab the stars by their throats? Did you wear the skins of dead galaxies, your eyes ablaze with impossible fury?.. Where were you when the collisions coalesced? When molten spheres blackened, flared, drifted and circled? What sounds did you know in the voice of the whirlwind?

Setting aside contemporary scientific references (cells, atoms, etc.), one can imagine this forming part of an ancient Mesopotamian text and becoming part of an animating mythology that might still resonate today.

But what do we learn of Evil?

Evil is relentless in its hunger for death and destruction, and unabashedly proud of the carnage always in its wake.

Here is the request Sparks and Kloss imagine Evil making immediately after its creation:

You must have said, ‘Father, make for me a friend so I may slay him.’

+

As strange as this might sound, one feels sorry for the one-dimensional Evil depicted in these pages. Its only pleasures in the death and destruction, yet “even a man’s death, no matter how dreadful, ceases to amuse, after a time. How well you know this already.”

For all its sinister malice, the anthropomorphized Evil presented by Sparks and Kloss is essentially a flat character.

Recall if you will E.M. Forster’s discussion about “flat” versus “round” characters: “The test of a round character is whether it is capable of surprising in a convincing way. If it never surprises, it is flat.”

Evil will never be anything more than evil; it has no existence outside its conceit; Evil is flat; Evil never surprises.

Yet flat characters, like the straight man in a comedy duo, serve a purpose: to let its opposite shine, and in this collection, the vignettes most closely focused on human interactions are the ones that shine brightest.

Early on, Evil wakes to the “sound of the man in the garden” as he goes about naming “the animals and the creeping things.” Evil stands in soundless awe at this audaciously constructive and creative act.

[Man] named them with his godliness, with his upright posture, with his opposable thumbs…

… And then there was woman. And she was nothing special. But she was wide in places, and she was narrow in other places… And I waited. And now he set about naming her….

First, he named her “Mine.”

… He named the parts of the woman who lay before him, wide parts and narrow parts, pink part and white parts, soft parts and hard parts, dark parts inside that drew him like honey. He named her with his moans, with his brute thrusts. He named her with heavy breathing..

As Evil follows man around through the millennia, we sense envy. We sense a desire to be, well, more than its conceit.

It was good to be present at the birth of people. To understand how something so pink and frail survived the forest. How they learned to shape clay, to use stone tools, when the only implements I needed were those I was created with, the claws and the teeth, the merciless ravaging soul…

I watched them from the shadows, the rise of their glory. I watched them from the cold red shadows, shivering in my only-ness.

What evil lacks is the capacity for love: “The out-of-reach, the indescribable, the thing you were born without; and no matter how much skin you inhale, no matter how many bones you snap, you will never learn to satiate [your need for] it.”

Unlike Evil, which does not build but only devours and destroys, mankind has constructive capacities and seeks to make sense of its surroundings.

This is not to say that mankind is incapable of evil. Even the Enlightenment — “an age of mathematics and formula, of calculations and chemicals, of rhetoric and philosophy” — was “an age of murder and suspicion and terror, an age of bread riots and informants and double-dealings and bloody streets… A cold age of cadavers and cutthroats, of men evolved to something almost echoing you.”

The collection’s stand-out vignette takes us to Cairo of the 1920s, to a party celebrating the opening of Tutankhamen’s pyramid. Evil is “dancing something called a foxtrot” with a beautiful English archeologist. The desire that Evil feels for this lady is palpable in nearly every sensuous word.

Her dress is gold and her skin is gold and her hair is gold, bobbed short to show her long and lovely neck and naked back.

It is a warm and lovely night and there are too many stars to count, and your companion is graceful and sleek as a cat. Her ear is a seashell, pink and cool. I have eaten many priests of this land, you whisper into it. She smells of honeysuckle and roses and something muskier, too. It will be worth it to peel the flesh from those long white arms, to pop them like grapes and suck the buttery marrow. Your skin tightens around your bones and your arm tightens around her waist. You draw her closer. You breathe faster. You bring her chin up, breathe desire into her nostrils. The music changes, picks up pace, and you see the spinning chandeliers reflected in those dark eyes, the widening iris…

As close as Evil holds this woman, what he wants from her — something approaching love — is, for Evil, unattainable.

You could murder her now, but sometimes it is hard to be alone with so many dead things. Sometimes you grow weary of death.

+

Ben Marcus, who has rightly earned an exalted place in the firmament of contemporary experimental fiction, recently spoke about his like for bleak perspectives:

In the end I am uplifted, profoundly so, by the bleakest, despairing work. It’s a great unburdening to read work of this sort. I do not want to be asked to pretend that everything is all right, that people are fundamentally happy, that life is perfectly fine, and that it is remotely ok that we are going to die, and soon, only to disappear into oblivion. I feel a kind of ridiculous joy when writing reveals the world, the way it feels to be in the world. That’s what hope is, a refusal to look away.

Make no mistake: The Desert Places is an unfailingly pessimistic book. A vignette set in some vaguely futuristic time period, begins thusly:

The girl in the trash receptacle is not really a girl. Not anymore. She’s a trail of destruction, the crumpled instructions on how to steal the life from a body. She is an eye, several fingers, a hand, a foot: a pile of teeth and hair and toenails. She is a heap of dead skin cells.

Implicit in this tight language is the fact that this girl was once much more than presented here — she once was alive.

Yes, we are doomed. We know that we will die. This is not, as Marcus says, “remotely ok,” but it is true.

Don’t flinch from this vision that Sparks and Kloss present. Yes, evil lurks around us, but in its periphery exists mankind, with its dueling capacities for good and evil, and with its capacity for love and beauty, innovation and invention — all of which are beyond the capacity of unalloyed evil.

Is that what hope is? Knowing that, as tarnished and imperfect, as doomed to death as we are, we are always more splendid as Evil?

+++

+

+

+