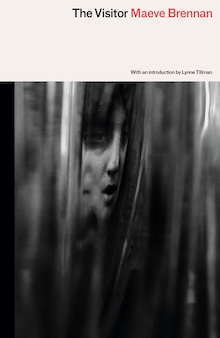

Peninsula Press, 2025

The experience of a young adult returning home after a long absence is not always a simple one. Warm feelings of nostalgia mingle with darker memories—the ones childhood so expertly preserves. Compounding the interior turmoil is the exhausting daily task of presenting a new self to those who persist in seeing only the former child and not the grown person that child has become.

Irish writer Maeve Brennan explores this experience against a backdrop of intensifying isolation and shame in her tense and understated novella. The Visitor follows 22-year-old Anastasia as she grieves and, in a mesmerizing finale, comes to terms with her status as an unwanted guest in her paternal grandmother’s home in 1930s Dublin.

For six years Anastasia has lived abroad to care for her ill mother, who fled to Paris from an unbearable existence in Dublin. Anastasia’s father has meanwhile died, partly of heartbreak from his daughter’s decision to stay in Paris with her mother. For Anastasia it was not a matter of choice. She could not leave her fragile mother. Resuming her middle-class Dublin existence with her father and grandmother was impossible.

When her mother dies, Anastasia returns to the house where she grew up. Her excruciating civility shrouding a seething rage, the grandmother—as this character is referred to throughout the novella—embarks on a campaign of judgment and rejection of her granddaughter.

Anastasia is left to grapple with her unanticipated status as visitor in a house haunted by a ghost train of childhood memories both comforting and menacing. “Home is a place in the mind,” Brennan writes, infusing her sparse prose with richness and volatility. “When it is empty, it frets. It is fretful with memory, faces and places and times gone by.” Anastasia is propelled into this “mirror for emptiness,” where her hopeful search for loving approval turns to retribution.

Orbiting Anastasia’s world is a cast of suffering women: one is bedridden for thirty years; another has lost her hair to illness; a third meets her demise on the train tracks when “[a] humour took her.” At the centre is her mother, whose specific demons are unexplained except through Brennan’s sketches of isolation, loneliness, and ill health. The book’s claustrophobic domesticity envelops its characters, who give outsized attention to the opening and closing of windows and the arrangement of furniture and knickknacks. Brennan’s narration of the women’s meaningless, futile gestures conveys a mournful compassion for the littleness of their lives.

Anastasia’s sole acquaintance beyond her grandmother’s household is the timid and elderly Miss Kilbride, one of the few people who had showed kindness to Anastasia’s mother before she fled to Paris. Miss Kilbride’s every movement was dictated by her even more elderly mother, now deceased. Miss Kilbride does not dare change a thing about the house, recalling how her mother “used to joke and say I was her other self. Sometimes she would call me that. She would say ‘Other Self, I think the window has to be closed a little earlier today’; or something like that. Then we would laugh.”

The anomie of middle-class life surrounds Anastasia, and emerges from within as well, such as when she observes herself indulging in clichéd small talk and is “astonished at the dullness of what she was saying.” Anastasia later remarks, “We are all just the same, and yet we go over and over our little lives time and time again, looking at each other and talking earnestly.” In such passages, Brennan heartbreakingly captures the narrowness of human experiences, all so predictable to Anastasia, and demanding her equally predictable response.

More sinisterly, the harsh coldness of her environment takes hold inside of Anastasia as the novella moves towards its climax. Anastasia is speechless with fear when Miss Kilbride turns the portrait of Mrs. Kilbride backwards, to face the wall, as though rebelling against her mother’s tyranny. In time, however, Anastasia discovers her own modes of resistance against what oppresses her.

The Visitor itself has an interesting story. Written in the 1940s, it was only discovered in Brennan’s archived materials in the late 1990s and was published by Counterpoint in 2000, seven years after Brennan’s death. It is her only book-length work.

This new edition includes an introduction by the writer Lynne Tillman who, like Anastasia and like Brennan herself, takes notice of small things and the universes they contain. Describing The Visitor as one of the saddest stories she’s ever read, Tillman is captivated by Anastasia’s persistent hope. She remarks on Brennan’s exquisite style, surprising syntax, and how “the story is learned by indirection and inference, and remains mysterious, with as many clues as readers need to know and no more.”

Tillman’s observations explain in part why The Visitor feels remarkably contemporary, fitting on a bookshelf alongside more recent books, such as the similarly brief and luminous works of Claire Keegan. Peninsula Press is to be thanked for the chance to celebrate Brennan’s work by making this remarkable book available once again.

+++

One of The New Yorker‘s most admired writers, Maeve Brennan (1916-1993) was an Irish journalist and fiction writer whose work drew on themes of childhood, marriage, exile, longing, and rage. In her lifetime she published forty-one short stories, which were collected in two volumes In and Out of Never-Never Land (1969) and Christmas Eve (1974). The Long-Winded Lady, a collection of her “Talk of the Town” sketches, was published in 1969.

+

Sally Rudolf is a writer living in Vancouver, Canada. She holds a literature degree from the University of British Columbia and is currently enrolled in The Writer’s Studio creative writing program at Simon Fraser University.