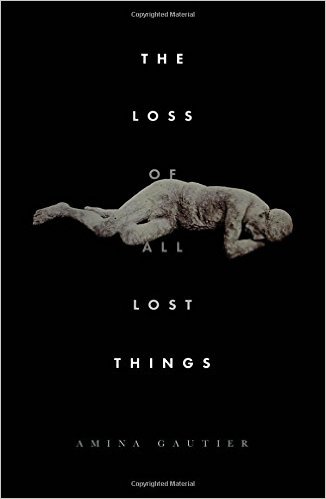

Elixir Press, 2016

Loss might seem like a straightforward concept, until a writer like Amina Gautier shows us that it isn’t. The fifteen stories in her latest collection, The Loss of All Lost Things, dissect the experience of losing things – people, places, dreams, youth – describing loss in its many moods and variations. For the most part, these are solidly realistic stories, devoted to showing us the details of life as many people experience it. As one would expect from a book about losing things, the stories are often melancholy; they feature lost children, lost spouses, careers, and dreams of having children or reconciling with one’s children. But the stories are also beautiful, with perfectly-turned endings that are devastating and satisfying both.

The first story, “Lost and Found,” sets the mood. In it, a boy has been kidnapped by a man he knows only as “Thisman.” He takes comfort in the thought that he has been lost because to be lost implies the existence of hope:

He prefers the word lost instead of taken. Lost is much much better. Things that are taken are never given back. Things that are lost can be found…He knows that there is a place for things that are lost.

To be lost means that he might be able to turn himself in to the Lost and Found, two words whose linkage he finds comforting. This is to be lost in the “right way,” where he need only wait to be found and in the meantime can stay in the reassuring company of the other lost things. Instead, he really has been “taken,” plucked off the street and ushered into a world that has been turned upside down. In this world, words aren’t reliable:

He has learned that this is something one can do with words, stretch them into softness and push them past their meaning.

He now has only his kidnapper’s words to guide him, and he believes them because he has no choice. To believe “Thisman” is lying to him would be to live with an impossible amount of confusion. It would mean not only being lost himself, but to have lost everything.

The title story “The Loss of All Lost Things” tells a similar tale, this time from the parents’ perspective. Their son was kidnapped while walking home from the bus. Again, the characters struggle with language:

It’s not as if [their son] has been misplaced. It’s nothing like losing one’s keys. It’s not as simple as retracing one’s steps. He has not been lost, but the proper word is too dirty a word that makes it all too real, makes them dread instead of hope.

Like the persona in Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “One Art,” the parents try to put their loss in perspective, listing the things they no longer have, the things other people have lost. But, as in the Bishop poem, it’s all a massive effort with disappointing results. The mother mourns her son, and she mourns the experience of loss itself. Yes, it is a common experience, but to think of loss as universal only adds to the weight of her pain:

Each loss, its own little death. She feels each loss so keenly, huddling there beneath her older son’s blanket, crushed and cowered by the loss of all lost things.

There are other stories about lost children, but also about losing youthful optimism and a certain flexibility of identity. In “What’s Best for You,” the protagonist Bernice finds companionship with a colleague at the library where she works. They are drawn to each other, and although she instinctively turns down his romantic overtures, she later thinks “Why not?” and makes her own overture in return. She is too late, though. He says no and then claims: “I understand, you know. You want to date somebody more your type. Somebody that’s been to school.” When she protests that she’s “not like that,” he says, “Everybody is like that.” She has been forced into a role, a stereotype, and can’t get out of it. She has lost a sense of possibility, not only about herself, but about human nature.

Not all of the stories are so bleak as these, though; many of them reach toward hopefulness, or at least allow the protagonist to glimpse new possibilities. “Resident Lover,” for example, tells the story of an academic at an artist’s colony who comes to see how transformative creating art can be. He and his wife have separated, and his strongest feeling about her is of how limp and lifeless her poems were. In contrast is Felicia from the artist’s colony, whose paintings are fresh and powerful, but even more important than the quality of the painting is her ability to lose herself in her work – an energizing, healing kind of loss:

Felicia painted tirelessly, only occasionally consulting the drawing tacked to the wall above it, never sparing him a glance. Felicia was gone from him, utterly absorbed in a way he could never be. He felt at peace there with her like that, with the music of the falling rain and the silence of no words.

The protagonist knows he is not capable of giving himself completely to his own creative efforts, but his glimpse of a true artist at work has made his life richer. He has lost a sense of his own personal potential, but gained a glimpse of what other humans can do.

Gautier’s stories are not linked in the sense of sharing common characters or settings, but they are carefully woven together around the theme of loss and beyond that as well. Many stories are set in an academic context or feature academics who have left that world in search of something else. They explore how the sometimes-insular world of graduate school and faculty life can isolate people and lead to their own peculiar forms of loss and loneliness. They are often in subtle ways about race. For example, “What Matters Most,” is told in the second person, with the “you” of the story as an African-American woman who is both attracted to a Puerto Rican man but also ambivalent about their cultural differences. “Intersections” tells the story of a white professor attracted to an African-American graduate student and certain that he can see a map of his future in the braids of her hair. Hair is an important motif in many of the stories in the way it can encode racial and cultural differences as well as become an indicator of emotions, moods, and even status.

The collection strikes a balance between enough common ideas and themes to feel like a coherent whole and enough variety of character, setting, and stylistic choices to keep a reader engaged from story to story. Readers who enjoy realistic fiction that captures truths about human experience, even the darker sides of human experience, will appreciate Gautier’s accomplishment.

+++

Amina Gautier is the author of three award-winning short story collections: The Loss of All Lost Things, which won the Elixir Press Award in Fiction, Now We Will Be Happy (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), which won the Prairie Schooner Book Prize, and At-Risk (University of Georgia Press, 2011), which won the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction. More than eighty of her short stories have been published or are forthcoming in journals such as Antioch Review, Crazyhorse, Iowa Review, Kenyon Review, and North American Review. Her stories have also been reprinted in several anthologies and have won the Crazyhorse Fiction Prize, the Danahy Prize, and the William Richey Award, among others. She received her BA and MA in English Literature from Stanford University and her MA and Ph.D. in English Literature from the University of Pennsylvania. She is on the faculty in the University of Miami’s MFA program.

+

Rebecca Hussey is an incessant reader, a critic, and an English professor. She teaches at Norwalk Community College in Connecticut. You can follow her blog at Of Books and Bicycles and find her on Twitter at @ofbooksandbikes.