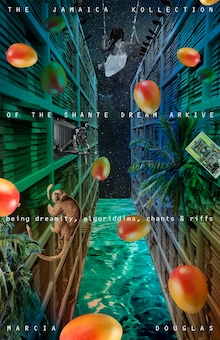

New Directions, 2025

In 1936, the American writer Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1960) traveled to Jamaica on a Guggenheim fellowship to study folk traditions there and in Haiti. On the way, she lost her camera. The detail hangs like a tantalizing thread from her account of her experiences, Tell My Horse (1937). With The Jamaica Kollection, Marcia Douglas has pulled that thread, unravelling it to produce a contemporary epic of displacement and resistance.

The second in a projected trilogy, The Jamaica Kollection is part of Douglas’s “speculative ancestral project” to describe “Caribbean migration and fugitivity, and the relentless ways in which stories and species change and transform; disappear and return; collide and mash up and rise up.” It follows several characters who are related in different ways across time and space, as they confront racist and xenophobic people, attitudes, expectations and structures, mainly along the western ridge of the Atlantic, from the northeast of the United States to the shores of Jamaica where Douglas grew up in the 1960s. Her central concern is storytelling, its difficulty, its power, and its long hold on her attention: “Years later and I stand in wonda of how our stories layer and where and how we come to find them.”

At the novel’s heart is a young woman known to the reader only as 20A, an immigrant from Jamaica who, as the novel opens, is living in a drab room in Newark. One day she hops a bus to the Grand Canyon, searching for “America at its most open-hearted,” a place “wide enough and big enough to hold everything,” where she will go and “shout her name.” On her journey she meets fellow travelers from different times and places, most of whom have some connection to Jamaica. There is the runaway Laverne, who in 1937 finds Zora Neale Hurston’s camera loaded with undeveloped film; Quaco, a time-traveling boy who is Zora’s friend; and Abba, an enslaved Jamaica woman who arrives on a Virginia plantation in 1788. To give an idea of how all these figures are linked: It is Quaco’s foot that appears in a photograph developed from the roll discovered on Hurston’s camera.

I offer this bare outline tentatively; another reader might find different points of emphasis. That’s expectable: Archives are not stories but matrices from which stories might be constructed and elaborated. Douglas shifts quickly and deftly among characters, times and places, with a lightness that makes questions of chronology seem pedantic if not wholly beside the point. I’m a fan of this kind of difficulty. I like the challenge of sitting with ambiguity, developing what Keat’s called “negative capability,” the capacity to resist “irritable reaching after fact and reason.”

It’s not that Douglas leaves sense-making as an exercise for the reader. She doesn’t. But she leaves her story open and indeterminate. Why? One hint is the Jamaican swallowtail butterfly, whose image flits through these pages. Its six-inch wingspan makes it the largest butterfly in the Western hemisphere. It is found only in the rainforests of eastern Jamaica, and it is endangered to due habitat destruction. To pin down the novel’s chronology feels like pinning one of the few remaining examples of this marvelous creature to a specimen board. Why would you do that? What would you gain?

For Douglas, the impending loss of the Jamaican swallowtail also spells the end of a particular form of consciousness. “Do not collect these butterflies,” she warns. “Do not disturb their habitat. For then there will be less dream in the wide-awake and less wide-awake in the dream.” This knowing yet oneiric lucidity Douglas sees as characteristically Jamaican. It’s also challenging. To take it seriously is to take seriously the possibility that ordinary habits of open-mindedness are neither open or nor mindful enough.

An “arkive” is Douglas’s term for the collection of scraps and fragments that she has brought together here in codex form. Not all of them are textual. Her gorgeous accumulations include sketches and drawings, including a particularly moving glyph of a hurricane, familiar from ominous weather reports, that becomes an emblem of ecocide. This practice of accumulation is tied to Jamaica as well—its practices, its forms of life. Take, for instance, the homemade “pretty paper,” made from scraps, that often lines the walls of people’s homes. It is an alternative to expensive wallpaper, but it’s also more personal than wallpaper, as an archive of what catches the eye, what is enjoyed, memorialized, and loved. Other papers also fill the archive: “free papers” found inside a family Bible that formalize the emancipation of a slave, for instance; and the nonexistent papers that 20A needs to prove that her presence within the territorial boundaries of the United States is “legal,” never mind the legality of the regime that demands such proof.

When a boy’s foot appears by chance in a corner of a photograph taken in 1936 and subsequently lost, it is a material trace of that boy’s existence, of his life in a world beyond the trace. Among other things, The Jamaica Kollection is a reminder that an archive is not, or not merely, a repository of traces. It can also be a source of inspiration, a springboard to vision.

+++

Marcia Douglas was born in the U.K. and grew up in Kingston, Jamaica. The author of novels, poems, and essays, she is the recipient of awards and fellowships from Creative Capital, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Whiting Foundation, and a UK Poetry Book Society Recommendation. Her third novel, The Marvellous Equations of the Dread was longlisted for the Republic of Consciousness Prize and the OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature. She is a College Professor of Distinction at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

+

Diane Josefowicz is Book Reviews Editor at Necessary Fiction, Senior Editor of Translation at The Adroit Journal, and the author, most recently, of L’Air du Temps (1985), a novella published last year by Regal House. Her story collection, Guardians & Saints, is forthcoming in October from Cornerstone Press; her second novel, The Great Houses of Pill Hill (Little Place of Departed Spirits), is coming in 2026 from Soho Press.