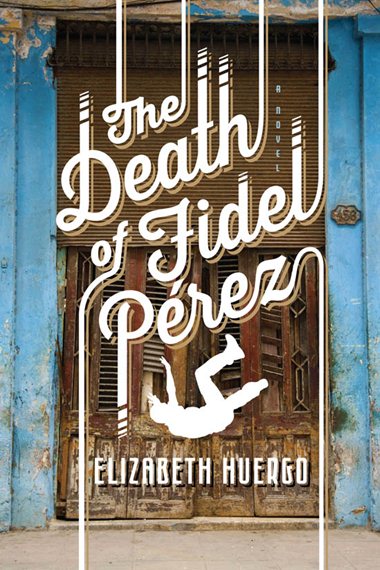

Unbridled Books, 2013

Set in Cuba in 2003 on the eve of the revolution, Elizabeth Huergo’s The Death of Fidel Pérez depicts the interconnectivity of history and its subjects in a deeply moving first novel. The novel begins with a heartbroken and drunken young man, Fidel Pérez, as he pines for his already spoken-for love, Isabel. He stumbles onto his brother’s dilapidated balcony, buzzing on cheap beer and questioning the cruelty of the universe, just as the balcony gives way. His brother tries to save Fidel, and they both fall to their inevitable death against cold and broken concrete. This inciting event is gravely misinterpreted through a series of whispers and hopes, as the death of Fidel Castro and his brother Raul. Huergo explores the Cuban zeitgeist through misunderstanding and miscommunication in a web of characters and their communal oppression of past, present and future political hopes. The novel imagines the inciting events that fueled the fervor that brought about the revolution.

The claws of the past rake and disturb the characters in the novel—all have suffered losses of loved ones, dignity and hope. The three unrelated central characters represent key layers of the movement and population. Each character leads a chapter, occasionally overlapping in small ways with a close third perspective that defies the time space continuum. History and the past eeks into their present like a virus, occasionally overwhelming the narrative, other times enriching it. At first the slippage is unsettling, but soon readers can easily slip along into each character’s personal haunting. History Professor Pedro Valle is haunted by the ghost of his best friend, Mario. Prof. Valle’s delusions of his dead friend Mario increase until the post-modern slippage destroys his reality. His guilt for having betrayed him during torture ends up driving him mad. Camilo, Valle’s firebrand student, is haunted by the loss of his mother, girlfriend and future. The local old sage, Saturnina winds through the city shouting “Fidel calló, Fidel cayó!” disseminating the misinformation until she feels fulfilled in making right the wrong that befell her when her son Tomás had “disappeared” through witnessing Camilo’s reincarnation as the leader of the revolution. These characters flicker in and out of each other’s lives as the temperature of the city rises.

Language in the novel also slips. Phrases that sound the same are used in exchange for one another. The dialogue buzzing about the misinformation of Fidel’s accidental death is captured in Beckett-like disembodied conversation:

“What did she say?”

“Both killed in a stroke.”

“They fell from the balcony.”

“He had a stroke?”

“Yeah, he had a stroke and fell.”

“His brother, too?”

“Raul saw his brother die!”

“Imagine seeing that go off.”

“The balcony was blown up?”

Spanish phrases are artfully used to interject powerful ideas about the revolution and add texture to the piece. Names of characters splice meaning further: Camilo’s girlfriend, Amparo, which means “shelter” or “protection” represents the home he never had but longs for. The Fidel Perez and Rafael Perez are confused for the Castro brothers. Each sentence is beautifully wrought and precise. The writing evokes elegance and a somber note that is like its subject, haunting.

Huergo balances past and present seamlessly, a sepia tone photograph against the brilliant yet harsh present tense. The novel asks a larger question about history: who is destined to become a part of it and who will remain nameless and absent from its pages? There is a fierce movement towards remembering those who died brutally during Batista and Fidel’s respective rules and those who were lost amongst the masses attempting to escape.

The Death of Fidel Pérez is a weighty history lesson through personal accounts that act like puzzle pieces to a larger landscape. Through these small moments we learn more about the insidious nature of tragedy, loss, and political oppression’s continuous influence on generation after generation. As the ghost Mario says, “Cuba is like a woman beaten by a succession of violent men, corrupted by a desire that has brooked all contradictions.” In this stunning début, Huergo achieves a postmodern homage to those who sacrificed their lives for Cuba’s revolution.

+++

Elizabeth Huergo was born in Havana and immigrated to the United States at an early age as a political refugee. A published poet and story writer, she lives in Virginia. The Death of Fidel Pérez is her first novel.

+

Olivia Chadha is the author of Balance of Fragile Things. She attended Binghamton University’s Ph.D. program in creative writing, and currently lives and writes in Boulder, Colorado. www.oliviachadha.com.