Apprentice House, 2016

Why did you disappear into the sky? This gentle question enters the story about halfway through Ellen Prentiss Campbell’s novel, The Bowl with Gold Seams, in a quiet scene between a father, his daughter, and the narrator of the novel, Hazel, who is looking after the daughter in a way of sorts. In the novel it is the line from a poem by Murasaki Shikibu, and the father and daughter read it together in Japanese, then translate it into English.

He pointed at each character, running his finger down the page. She joined in, hesitantly. Once or twice he corrected her. I couldn’t understand them, but the sound of their combined voices, hers faint, his deep—like light and shadow—was as pleasant as music.

On its own, the scene contains both grace and foreshadowing, and Hazel is a receptive witness to the scene’s surface elements as well as its undercurrents. But that first question of disappearance can also be stretched across the entire novel, and in this way becomes a framing query for the story’s interconnected plots and themes of loss and absence and, quite hauntingly, of war, too.

The Bowl with Gold Seams is a fine example of that genre of historical novel based on an intriguing footnote from the past. Like many of these books, what inspired the story may be quite small but it contains within it the echoes of much larger events. Historical fact: in the summer of 1945, the Bedford Springs Hotel in southern Pennsylvania was used as a detention center for interned Japanese diplomats. The novel: Prentiss Campbell imagines the time these diplomats and their staff members spent in the hotel through the eyes of Hazel Shaw, a young woman who volunteers to join the hotel staff during this politically charged moment. Hazel isn’t a disinterested worker, however, as her new husband—who was also her childhood best friend—has recently become missing in action in the Pacific theater.

That simple three-sentence plot summary does very little to actually detail the variety of stories winding their way through this deftly-executed novel, including the recent loss of Hazel’s father, a devoted Quaker who ran the local jail. Alongside Hazel’s personal story is the novel’s second largest plot focus—the Harada family and their unusual wartime situation of an English mother, a Japanese diplomat father and their mixed-culture child. Working as effective satellites to these two stories are short moments and descriptions looking at a few of the other Japanese individuals and families interned at the hotel. The novel covers the few weeks leading up to and just after the dropping of the atomic bombs and Japan’s surrender, and in this context that question of Why did you disappear into the sky? takes on another dimension that Prentiss Campbell subtly opens up for the reader—the image of the bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima and how this literally changes the world at that moment. She doesn’t linger on this macabre detail but it ghosts along behind the rest of the story in an echo of Truman’s famous words, “rain of ruin,” which Prentiss Campbell includes verbatim because no other description can be as chilling.

Again and again, the novel circles around this question of loss and absence. A father passes away, a husband goes missing, bombs are dropped, an old man dies in a kitchen, a child drowns, a family must separate…this could feel relentless and very dark, but the novel that Prentiss Campbell makes of all this remains more thoughtful than devastating.

Something else the novel does very well is capture how charged Japanese-American relations were at this point in history, and then explore the very thorny issues on both sides. The hotel’s “hosting” of diplomats was a difficult situation for many townspeople to accept, and the staff and the hotel must tread cautiously. These were not American citizens interned, as was the case in other parts of the country, these were high-ranking Japanese diplomats and other European-based Japanese staff and families that had been captured when Berlin fell to the Allies. These people were directly and unequivocally the enemy. Prentiss Campbell mines this situation for its political and human complications, bringing out the diversity of opinions and attitudes on both sides of the divide. It’s very honest, and very well done.

The novel is primarily focused on those specific weeks of the summer of 1945, but it is bookended by a present tense story that introduces and adds further meaning to those historical chapters. We first meet Hazel Shaw as a much older woman, a widow who works as the director of a private Quaker boarding school. An event in this forward story propels her backward into that fateful summer of 1945, but eventually we return to the adult Hazel to finally close up the story. It’s a satisfactory circular structure and the small revelations given to the reader in the last section do not overwhelm the power of the past tense story, which remains the novel’s heart.

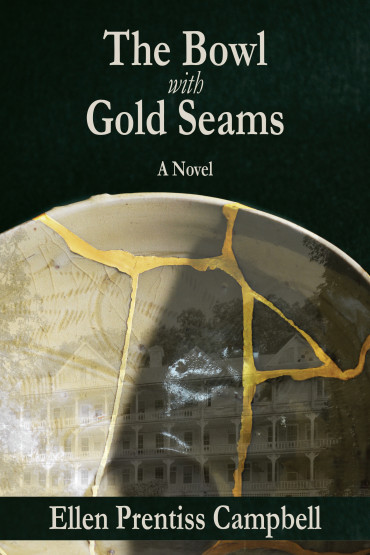

In his 1933 essay, “In Praise of Shadows,” the renowned novelist Tanizaki Jun’ichiro wrote eloquently on the play of darkness and light in Japanese aesthetics: “the beauty of a Japanese room depends on a variation of shadows, heavy shadows against light shadows—it has nothing else.” It’s quite fitting then that the key image for The Bowl with Gold Seams is a kintsugi bowl, a piece of pottery that has been broken and mended with golden glue. This is an object that boasts of its brokenness, even transforms that brokenness into its finest attribute. It’s an all-too-human paradox—like love in war, faith amidst death, kindness in return for cruelty. Gently then, carefully, the novel gives its reader light and shadow, broken and repaired.

+++

Ellen Prentiss Campbell is the author of the short story collection Contents Under Pressure. Her short fiction has been featured in numerous journals including The Massachusetts Review, The American Literary Review, and The Southampton Review. Essays and reviews appear in The Fiction Writers Review, where she is a contributing editor, and The Washington Independent Review of Books. A graduate of The Bennington Writing Seminars and the Simmons School of Social Work, she is a practicing psychotherapist. In both her writing and her clinical work she seeks the story between the lines and behind the words. Campbell lives with her husband in Washington, D.C., and summers in Manns Choice, Pennsylvania—near the Bedford Springs Hotel.

+

Michelle Bailat-Jones is a writer and translator. She is Translations Editor for Necessary Fiction. Her first novel, Fog Island Mountains (Tantor, 2014), won the 2013 Christopher Doheny Award from the Center for Fiction and Audible. Her translations include Beauty on Earth (Onesuch Press, 2013) and What if the Sun… (Onesuch Press, 2016) by Swiss author Charles Ferdinand Ramuz (1878–1949). Her short fiction, poetry, translations and literary criticism have appeared in various journals including The Women’s Review of Books, The Kenyon Review, Cerise Press, Spolia, Fogged Clarity, Two Serious Ladies, Xenith, Sundog Lit, Hayden’s Ferry Review, PANK (online), The Rumpus and The Quarterly Conversation. michellebailatjones.com