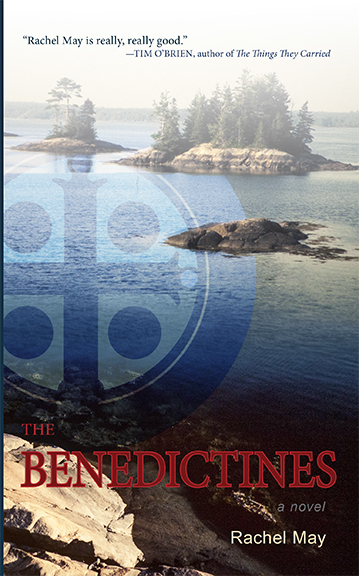

Braddock Ave Books, 2016

Rachel May’s debut novel begins with a lush description of coastal Maine, then zeroes in on the insular, almost idyllic St. Christopher’s, a boarding school run by Benedictine monks two hours north of Portland. The scene describes a “windy pine-tree coast buttressed by smooth gray rocks…an ocean of white caps…a wide sloping green lawn…the lighthouse on the far shore” plus lobster boats, barges, and tugboats in view of the campus. Our narrator is not from Maine, or a Benedictine, but an outsider who is mystified by the monks, the school administrators, and the adults who choose to work there. Annie James is a Colorado painter and lapsed Catholic who’s run from a broken engagement toward the paycheck and free rent she earns as St. Christopher’s “Visiting Artist.” On the first page, we learn that, for Annie, the beauty of the campus doesn’t balance out her reservations about working for a Catholic institution, or make her comfortable around the monks who run the school. Her alienation from the monks is absolute: “The teacher who lives down the road says his two dogs are scared of the monks. Says when the monks walk by in their robes, his two dogs bark at them. … They are a mystery, even to the dogs.” When she’s scolded by an administrator for hosting a male guest overnight, or when she’s forced to shut down the students’ conversations about sex with insincere exhortations of abstinence, she reminds herself why she came: she has no money. It’s only a two-year job.

Annie’s anger for being rebuked only amplifies her feelings of isolation. Her lack of connection to the school is reflected in the way she refers to colleagues—she regularly interacts with “My One Friend,” “Talking Man,” and “My Devout Roommate,” but she can’t bring herself to use their names. Despite knowing her time there is limited, conflicts with colleagues get to her. After a tense exchange with her roommate, she imagines the school’s dramatic end:

Sometimes, I imagine crumpling this whole campus up into a tiny little ball, and tossing it into the air, and casting it into the sea. I imagine how it will swirl and sink slowly—the church, the yellow Victorian, the Arts building, the Admin building, the wide green soccer fields, the great sloping Gatsby lawn—all of it swirling into the dark dark depths, where it will settle on the floor, and leave me, rescued and standing on the rocky shore.

Annie’s narration is interspersed with italicized chunks of text, excerpts from The Rule of Saint Benedict, which gives the monks and school administration a voice and explains the institutional values that are running Annie’s life. Other italicized sections are more fully realized descriptions of past events on campus and back home in Colorado. These sections give context and provide a glimpse of life before St. Christopher’s, what Annie is trying to escape, and what she’s hoping to return to.

May effectively captures the internal experience of being depressed and isolated. The majority of the narration comes in the form of Annie’s short, clipped sentences, which often seem at odds with the stream-of-consciousness nature of the text. The strongest feelings she experiences are rage, such as during a faculty meeting; anxiety, when students turn the conversation to subjects that could get her in trouble; and longing, when she speaks to loved ones in Colorado and imagines running back home. At the same time, she feels genuine affection for her students, wanting to reassure them. When one writes in class “about sex, and how Catholicism makes you feel so guilty about it,” her hands are tied: “I want to agree with him, but I cannot.”

Annie’s struggle against the structure of St. Christopher’s mirrors many Catholics’ feelings of betrayal by the church after stories of widespread sexual abuse and concealment became public. In the case of The Benedictines, Annie’s reckoning and choice to leave the church (which happened before the church’s scandal) are reawakened by her return to a Catholic high school and heightened when she is shunned in the cafeteria and shamed for her sexual choices. In the midst of these conflicts, there are small gestures that make her feel comfortable—a colleague invites her to join a game where school staff members are “cast” as famous actors. After adding names to the list, she thinks, “You are finally part of something here.” At the advice of friends, she attempts online dating. Trying again at love has a transformative effect on Annie—though she still chafes against the overnight rules, happiness leads her to be more generous with the people she disagrees with. As she becomes more open to her surroundings, her story widens, allowing readers to learn more about why she ran, from her life and from the church.

One of the great strengths of this novel is transcendence, individually and institutionally. Annie finds that beyond anger and disgust, there is empathy. The novel is populated with characters who vary in their relationships to the church and its dogma. Each of them is humanized, if not validated, by the end of the novel. At the end of the school year, Annie still wants to leave, but her anger is transformed into a peaceful acceptance of herself, as well as the colleagues she’s been in conflict with. Annie’s time at St. Christopher shows us that we may leave the institutions of our youths, but they never leave us, no matter how egregious their flaws.

+++

Rachel May is the author of The Experiments: A Legend in Pictures and Words (Dusie Press) and Quilting with a Modern Slant (Storey/Workman), a Library Journal and Amazon.com Best Book of 2014. An Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Northern Michigan University, her writing has been recently published in LARB, The Volta, Michigan Quarterly, Indiana Review, and many other journals, and she’s been awarded residencies from The Millay Colony and The Vermont Studio Center.

+

Rachel Mack is a writer and a practicing therapist in Louisville, KY. She collects her writing at rachel-mack.tumblr.com.