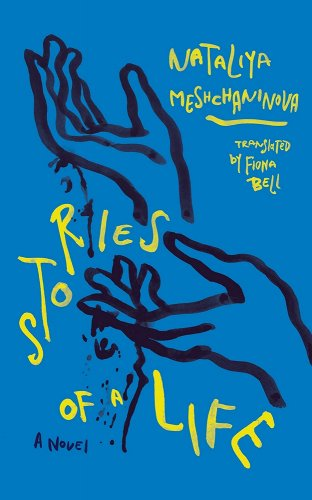

tr Fiona Bell

Deep Vellum, 2021

First published as a series of viral Facebook posts, Stories of a Life: A Novel by Russian filmmaker Nataliya Meschaninova thrusts readers into the world of a miserable Russian teenager in all her eye-rolling, gum-snapping glory. Rendered into a convincingly young, headlong, and informal English by Fiona Bell, this brief novel puts a social media spin on a gritty post-Soviet adolescence. It’s also hilarious.

The novel opens with a two-page chapter, “A Little Bit About My Family,” in which the narrator, the indomitable Natasha, introduces the sad-sack relatives—some luckless, others frankly predatory—who will, in the following pages, ruin her life. It’s an odd start, but the list of dramatis personae turns out to be highly necessary. This family is utterly chaotic, at once constantly enlarging and falling to pieces. Natasha’s capsule bios help keep track of them all.

Meschaninova has a formidable grasp of how a troubled teen might sound and act. Natasha is alarming and disarming, naïve and nuts. Stuck in a small town, she is at the mercy of a scattered and feckless mother. As the book opens, her parents have divorced, and she goes with her mother on vacation, a “nice trip to Taman” on the Sea of Azov. Reflecting on life without her father’s daily presence, Natasha is surprised to discover that it “wasn’t bad without him around.” But when he remarries and has a second family, she is shaken: “None of it made sense anymore, and I stopped thinking of him as my father. I suddenly realized that being a dad was a bullshit temp job, that you could quit or pick a new daughter whenever you wanted.”

Post-divorce, money is tight, and there are many mouths to feed. The chaos is exacerbated by the mother’s habit of bringing new children into the family: “This was my mother’s downfall: she loved nothing better than adopting people.” What’s at stake for Natasha is loss of belonging. When her mother claims that her sister, who doesn’t look like either of her parents, is actually an adoptee, Natasha worries. She does not strongly resemble her parents either. “Did that mean I was adopted too?” When Natasha misbehaves, her mother stokes this simmering fear. “As soon as I pulled a stunt, my mom would say, ‘Well, of course—she’s not one of us!’”

The household’s economic crunch is unbuffered by love, kindness, or plain cooperativeness—whatever it is that keeps families together under difficult circumstances. Everyone’s fighting to survive, and they’re mainly fighting each other. When one of the new arrivals, Lena, outstays her fragile welcome, Natasha’s mother tries to think of a way to get rid of her. “She started throwing around the idea of a hitman. I’m not joking. It was the nineties,” Natasha deadpans, “and finding an affordable hitman was a piece of cake.” Finally the mother kicks Lena out. But the restored peace is fleeting. Lena returns, trailing more trouble in the form of a son who years later returns to ransack the apartment. Natasha drolly sums up her mother’s predicament: “Getting rid of Lena wasn’t in her cards. Finders keepers.”

Into this mess comes yet another bad actor, a man Natasha calls “Uncle Sasha,” one of her mother’s lovers who sticks around raising everyone’s hopes—perhaps there will at last be a nice home, abundant food, new appliances—while he sexually assaults Natasha. This betrayal, compounded by her mother’s serene denial of her suffering, crystallizes the narrator’s desire to escape to Moscow, where she hopes to start a new life. The penultimate story,“Desire,” traces this trajectory. Natasha begins with a winsome report: “I make a wish on a strawberry.” But since the object of the chapter’s ambivalent desire is Uncle Sasha, the winsomeness devolves rapidly:

I make a wish on a strawberry.

On a plane’s contrails.

On a wave.

I wish he’d get hit by a tram.

Each chapter in Stories of a Life reads like a desperate letter penned in haste and foisted on someone, anyone, in the world outside this awful family. Consumable as popcorn, the stories are perfect for social media. Their success in that milieu is not at all surprising. But presented in codex form, Natasha’s dashed-off messages accumulate heft and dimension. As Natasha comes more fully into view, her despair becomes palpable. She is so armored, so closed off, that she no longer cares why her mother failed to protect her. “I don’t even want an answer anymore,” she writes towards the end. “That’s life, we’re alive and well, what more do you want.”

+++

Nataliya Meschaninova is a filmmaker in the vanguard of new Russian cinema. In 2017, she broke into the literary scene with the viral hit Stories of a Life, which became a pillar of the #metoo movement in Russia.

+

Fiona Bell is a literary translator and scholar of Russian literature. Her translation of Stories of a Life received a 2020 Pen/Heim Translation Fund grant. She lives in New Haven, Connecticut.

+

Diane Josefowicz is editor of reviews at Necessary Fiction and the author of Ready, Set, Oh, a novel published earlier this year by Flexible Press.