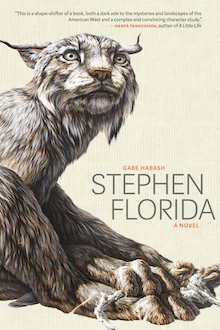

Coffee House Press, 2017

The debut from Publishers Weekly fiction reviews editor Gabe Habash, Stephen Florida, is different from so many other contemporary novels. Those differences will inevitably turn off some readers, but if you’d enjoy an intense dive into the consciousness of a vile yet fascinating narrator, this is your book. Dark, engrossing, and unendingly weird, Stephen Florida is a tribute to the beauty and terror of obsessive madness.

Stephen Florida, our titular narrator, is a wrestler in his senior year at Oregsburg, a small college in rural North Dakota. His parents are dead, and he lives off the money they’ve left him. But Stephen isn’t interested in wealth or people. His one goal is winning every wrestling match he can and making his way to the national championship in Kenosha. Stephen sleeps, eats, dreams, and hallucinates about his matches, his wrestling opponents, and his superiority over a corrupt and lazy world. He’s plagued by alternating visions of weakness and megalomania, personified by a mysterious, haunting entity known as frogman. Stephen pays strong attention to body fluids and the foul minutia of life as a way of illustrating his low opinion of every other human being. This attraction to all things gross—along with Stephen’s lonely, violent, and obsessive nature—seems reminiscent of Iain Banks’s The Wasp Factory. Stephen is a character consumed by ambition, both admirable and terrifying:

I keep up the task of finding out how the world works, locating its pulley systems, and placing myself in the center. Facts: A human thighbone is stronger than concrete. The stuff in a camel’s hump comes out green. I didn’t learn these things without falling off the horse. Get back on the horse. That’s a fucking saying you’ll have to get used to if you’re going to find your center. Inherent in it is how fucking repetitive getting back on the fucking horse is. Get back on it. Get back on it. Tell yourself you’re not a wastrel, you’re not carrying on for nothing. Drink your green camel-hump juice and say to yourself you’re not a wastrel. Find your center and fuck it until it’s pregnant with your little babies so they can come out and find more centers to fuck.

The narrative perspective is closely aligned with Stephen’s view so that the entire novel reads as a long diatribe from his warped brain. The character’s arrogance and paranoia frame the novel, and Habash’s writing style feeds these feelings of barely veiled menace behind every corner and stranger. A wealth of odd side characters confirms Stephen’s dark view of humanity: predatory Coach Fink, murderous jazz teacher Silas, manipulative Aunt Lorraine, and the list of wrestlers who have beaten Stephen in the past. Another set of characters initially give Stephen social grounding, especially girlfriend Mary Beth and wrestling mentee/frenemy Linus. But eventually these relationships turn toxic and only add to Stephen’s neurosis.

More than anything, Stephen Florida is an accomplishment of character. Stephen is dark, complicated, and disturbing, yet the force of Stephen’s desire to be a champion wrestler compels the reader to root for Stephen, even when he acts like a serial killer. This sympathy for Stephen comes from the infectious passion he conveys for his art, for wrestling. Habash puts us deep into Stephen’s enormously focused drive by flooding the page with florid, tyrannical language that races through Stephen’s mind during his wrestling matches. Here’s a section from Stephen’s first senior-year bout:

When I kneel down beside him, through my fingers I can sense in his skin his anxiousness to get out from the bottom so he can ride a 3-1 lead and resume the fishing game we just spent a period playing. … I place my ear on Brett’s back and hear his heart. “Oh, Brett, I told you I was going to eat you,” I whisper to him. Something like sympathy, I could fall asleep if we stayed here long enough.

But the universe shakes its rainstick, and the course of history follows the only path it was ever going to, and I imagine there is a sadness in seeing, from the bleachers, the exact steps Brett takes in the exact spots he’s supposed to, exposing himself to the conclusion, which is my forearm against his nose and his weak, frenzied exhales before he stops struggling and I push him down like a planting root, like burying a secret, and pin him. There are a few handclaps when my arm is lifted, and I walk back to my corner of spit down the hall and spout nonsense I’ll never remember. This feeling, which lasts about one minute and then it’s gone, is completely round and full and soggy, and it lifts me out of everything bad. I’m completely mad with it.

The writing gives us an unsettling glimpse into Stephen’s mind and also makes following the wrestling matches surprisingly easy and interesting, even for a reader who knows nothing about the sport. Stephen’s sheer intensity pulls the reader through every wrestling scene. These matches are the highlights of the book in which Habash’s style shines brightest.

On every single page, the sentence-level writing is spectacular. But the book’s structure does falter in the middle of the novel. There’s a long stretch of text in which Stephen—for reasons this review won’t give away—is without any clear motivation or goal. We dive deeper into his twisted psychology, but this reader found himself feeling aimless, wishing for the return of a stronger plot thread or for more of the powerfully written wrestling matches. A stronger storyline does eventually emerge, but those looking for clarity and plot resolution will be left disappointed. Style, character, and tone carry far more weight in this book. The main draw of the novel is Stephen himself and the bizarre, obscene, and intriguing worldview he brings.

Stephen Florida is a book about testosterone gone mad. As the novel progresses, Stephen’s sense of self and the world around him spiral down into greater depths of insanity: “There is no real Stephen Florida. I am only a giant collection of gas and light and will.” You’ll have to read the book to find out how Stephen’s wrestling season concludes, but the plot is ultimately dwarfed by the enormity of Habash’s invention, the strange, disgusting, irresistible title character of Stephen Florida.

+++

Gabe Habash is the fiction reviews editor for Publishers Weekly. He holds an MFA from New York University and lives in New York.

+

Caleb Tankersley won the Wabash Prize in Fiction from Sycamore Review and the Big Sky, Small Prose contest from CutBank. His work appears in Gargoyle, Permafrost, Storm Cellar, and other magazines. His chapbook Jesus Works the Night Shift was published by Urban Farmhouse Press. Currently, he runs the creative writing program at Mississippi School of the Arts and is a reader for Memorious.