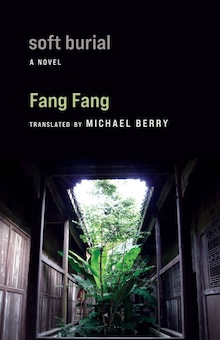

Columbia University Press, 2025

In Fang Fang’s letter to readers at the end of Soft Burial, she defines the meaning of her novel’s title as the act of being “put into the earth without a coffin,” such that “one’s body [is] placed directly into the dirt.” Such a departure, with its implication of suffering in the life to come, forms the crux of Soft Burial. In the face of China’s Land Reform Movement, Fang’s characters must resign themselves to dishonorable burials. In her story, a contemporary Chinese family uncovers the country’s recent history and grapples with this question of how to honor the past. Soft Burial questions the value of information and the ways in which it is delivered and received, acknowledging the pain of the past yet quietly suggesting that remembrance is critical to an honest civilization.

The novel opens with a nameless elderly woman who, suffering from amnesia, remembers only the most recent decades of her life. This second act of her life began when she is found in a river in critical condition. She later marries the doctor who both nursed her back to health and also named her Daiyun when she could not remember her name. Though her husband has died by the time Soft Burial begins, her son, Qinglin, has found success in his career as an architect and buys his mother a beautiful house. Daiyun’s move to this new home triggers a traumatic response, and she enters a vegetative state.

As Qinglin works long hours, he grows closer to his boss and his boss’s family while his mother remains unresponsive in her new home. The story oscillates between the two worlds, following Qinglin on his various projects and his mother as she dreams herself chronologically backwards through her life, particularly the suffering she endured during the time of land reform. In reference to Diyu, a Chinese mythological concept referring to eighteen stages of suffering after death, these memories are spread over eighteen levels of hell.

Qinglin grows close to his boss’s father, Liu Jinyuan, who is a former commissar for the Chinese Communist Party. Jinyuan fought against the bandits during the Land Reform Movement, the violent campaign that followed World War II and ultimately informed modern land classification throughout the Chinese countryside. During this time, the Chinese Communist Party forcibly redistributed the wealthy’s estates to the peasants who worked the land. Considered a success by Chinese leaders, this movement reshaped Chinese society while subjecting landowners to a great deal of violence. Through Jinyuan’s stories, Qinglin learns of this period in his country’s history for the first time, and he struggles to understand why such violence was accepted.

This story, as it jumps between perspectives and time periods, introducing new characters at each junction, might have been a difficult read. As a reflection on recent Chinese history, the text is full of references that might not resonate either. But the slow drips of Daiyun’s backstory are released at a carefully calibrated pace that keeps the reader grippingly engaged. The text’s structure subtly reflects the way certain revelations shape characters’ experiences. Thanks to the translator, Michael Berry, the text flows beautifully, and for all its challenges, the novel abundantly rewards the reader as Qinglin’s hunt for answers about his family’s past forms an ever stronger centripetal force.

Soft Burial is not simply a recounting of China’s Land Reform Movement, but also a narrative reflection on the ways in which the revolution’s effects have shaped modern Chinese culture. The empathetic bipartisanship by which Fang recounts this critical moment in China’s past is Soft Burial’s most compelling quality. It also attracted the scrutiny of the CCP, who, in their telling of the success of this campaign, have deliberately omitted any details that might paint the movement in a negative light.

The author is exceedingly familiar with the fragile matter of record. A novelist for many years, Fang rose to prominence in 2020, when she wrote a blog from the epicenter of COVID-19, telling her followers about pandemic life in Wuhan. Like Soft Burial, those writings landed Fang in trouble with the CCP and its supporters, who criticized her account of the Chinese response to the pandemic as unpatriotic and inaccurate.

Fang contends that “when the living insist on consciously or unconsciously cutting themselves off from what happened” and “refusing to remember, this is another form of soft burial. […] And once the past has been committed to a soft burial, it will likely lie there generation after generation.” In contrast, when faced with painful insights, Fang chooses to “sit down and diligently commit [her] knowledge, feelings, confusions, and pain to paper.” But not all of her characters share this clear belief in the truth. By Qinglin’s calculation, “time goes on forever, eventually giving a soft burial to everything that is real. Even if you think you really know something, how can you be sure that it is the entire truth?” Fang offers no easy resolutions, leaving the onus on her audience to determine the intended role of record in histories personal, familial and societal.

+++

Fang Fang is the pen name of Wang Fang, one of contemporary China’s most celebrated writers. Her books in English include The Running Flame, also translated by Michael Berry. Fang Fang’s account of the COVID-19 lockdown in her hometown, Wuhan Diary, was translated into twenty languages and garnered critical acclaim from major media outlets around the world.

+

Michael Berry is professor of contemporary Chinese cultural studies and director of the Center for Chinese Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles. A Guggenheim Fellow, he is the author of several books, including Jia Zhangke on Jia Zhangke (2022) and Translation, Disinformation, and Wuhan Diary (2022). He is also the translator of numerous books, including Fang Fang’s Wuhan Diary: Dispatches from a Quarantined City (2020).

+

Mia Carroll is an engineer and writer. She lives in Manhattan with her husband.