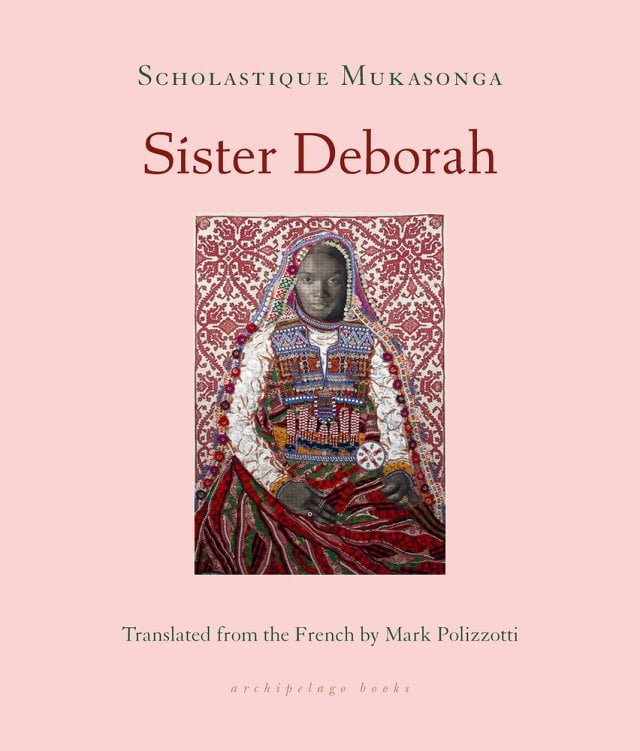

Archipelago, 2024

Sister Deborah by French-Rwandan writer Scholastique Mukasonga, translated from the French by Mark Polizzotti, begins in 1930s Rwanda with the arrival from the United States of a group of Black evangelical Christians preaching of a Black Jesus who will arrive on a cloud. The Americans bring with them Sister Deborah, a young woman noted for her healing abilities and for speaking in tongues. Ikirezi, a sickly little girl, is brought to Deborah, who heals her. Afterward, Ikirezi becomes fascinated by Deborah’s story: “I gathered up these scraps of tales and I preserved them like precious jewels in a corner of my memory, not knowing then that it would be up to me, later, to tell the story of Sister Deborah.”

The American missionaries and Sister Deborah become the center of conflict between men and women, between colonial powers and a local chief, between the new Pentecostal faith and the local Catholic and traditional belief systems. By the end of the novel’s first section, Sister Deborah is shot and possibly killed by colonial authorities, and the mission is disbanded.

Ikirezi later becomes an Africanist scholar at Howard University. She attributes her success to Sister Deborah’s healing powers. In the novel’s third section, Ikirezi, now called Deborah Jewels, tracks down Sister Deborah, who has not died after all. Sister Deborah relates her life story, from her Mississippi childhood to becoming a healer and a prophet, even perhaps a female Messiah. Sister Deborah has learned, however, that “spirits never come when you expect them, or even when you don’t expect them, no matter what the Gospel says.” Instead, she now preaches the virtues of hope and patient waiting. She tells Ikirezi: “I know this now, the spirit will never come. Yet we must wait for it regardless, and I announce the arrival of She-who-will-never-come.”

In the fourth and final section of the novel, Ikirezi learns of Sister Deborah’s violent death and knows she must return to the Nairobi shantytown where she had last met her. This new journey is personal, not scientific. Irikezi is searching for more about how Deborah had transformed her into the woman she now is. In Nairobi, Irikezi learns more about the death of the healer and meets her last followers, old women who reveal more of Deborah’s prophecy.

Scholastique Mukasonga was born in Rwanda, studied French in Catholic schools, and moved to France in 1992. In 1994, during the Rwandan genocide, thirty-seven members of her family were killed. Mukasonga has published memoirs about her early life experience as a Tutsi girl in Rwanda; more recently, with novels such as Sister Deborah and Kibogo, she has turned to fiction and tales of colonial Rwanda under Belgian rule. Mukasonga’s works often have the feel of a folktale, and the writer frequently speaks of the influences of her mother’s stories and of the oral traditions of her people. The character of Sister Deborah has ties to the Rwandan figure of Nyabingi, a female spirit whom Mukasonga’s mother invoked at times of serious illness.

In choosing to write novels about times before her birth, Mukasonga is addressing a feeling of obligation to report on the history of her people, not only events that she directly witnessed but also events from its colonial period. Of an earlier novel, Mukasonga says in an interview: “The novel, it’s true, allowed me to adopt a certain distance from my personal history, by recourse to fiction to touch on themes like the history of Rwanda and its falsehoods, the feminine condition, or the clash between the traditional religious beliefs and the importation of Christianity in all its forms.” Sister Deborah is part of a life’s work to restore that Rwandan history. In a Télérama interview, Mukasonga explains what compelled her to write the novel: “This work is a way for me to exorcise what I lived through in the past. I am part of a generation that has been completely erased of all trace of what was our precolonial religious culture, which was the foundation of Rwandan society. The genocide was a shock wave at all levels. We have to psychologically reconstruct ourselves, but also rehabilitate the narrative of our nation.” (The translations are mine).

Mukasonga includes in her writing specific Kinyarwandan words, wisely maintained by translator Polizzotti: isato (snake, python), kigabiro (sacred wood), and iriba (spring, well, watering trough for cows). These inclusions enlarge the reader’s vocabulary while opening the English language to new words from the African continent. In another interview, Mukasonga compares her use of these words “to the pebbles with which Le Petit Poucet,” a fairytale figure, “fills his pockets and which allow him to find the path back to his mother’s house.” Like those pebbles, the words “permit me to remember where I come from” (translation mine).

The need to remember where she comes from drives both Mukasonga’s writing and Irikezi’s final journey to Africa. Irikezi has become a noted scholar but has not forgotten the sickly little girl who was healed by Sister Deborah and set on the path from Africa to the United States. Deborah herself may be gone, but her prophecy is not done with Irikezi who continues Deborah’s legacy of waiting for “She-Who-Is-to-Come.”

+++

Scholastique Mukasonga was born in Rwanda in 1956. She settled in France in 1992, only two years before the brutal genocide of the Tutsi swept through Rwanda. Her groundbreaking books include Our Lady of the Nile, Cockroaches, Igifu, and National Book Award-nominated The Barefoot Woman, translated by Jordan Stump. In 2021, she won the Simone de Beauvoir Prize for Women’s Freedom.

+

Mark Polizzotti has translated more than sixty books from the French. His translations have won the English PEN Award and have been shortlisted for the National Book Award, the International Booker Prize, and the NBCC/Gregg Barrios Prize, among others. The author of twelve books, his essays and reviews have appeared in The New York Times, The New Republic, The Wall Street Journal, ARTnews, The Nation, Parnassus, Bookforum, and elsewhere.

+

Shara Kronmal’s essays have appeared in PLEASE SEE ME and in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Her literary translations can be found in Hunger Mountain Review and MAYDAY, and her reviews and interviews have appeared in CRAFT, Necessary Fiction, Chicago Review of Books, and elsewhere. She is the associate editor for longform creative nonfiction at CRAFT and is a retired Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist. She lives in Chicago.