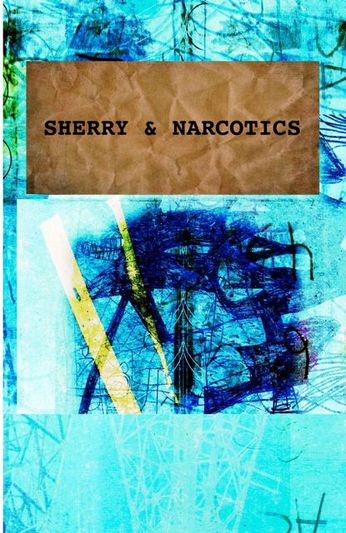

Future Fiction London, 2011

It isn’t easy to publish a love story these days—somehow we’ve all decided this is the stuff of cliché. As if the back and forth success and failure of looking for love doesn’t concern most people most of the time. Which is why Nina-Marie Gardner’s Sherry & Narcotics stands out in its genre of contemporary urban fiction. Here is a novel whose central movement is fixedly concerned with a young woman and a young man and whether or not the two will find a way to be together.

It is the details of any story that destroy that dreaded cliché, both the particulars of the writing itself and what the writing describes. In the case of Sherry & Narcotics this works on both levels. In terms of story, Gardner is decidedly un-mainstream in that she offers up a main character with little to endear her to the reader in the traditional sense. Mary, a playwright, is very much an average American twenty-something but she happens to be in the midst of some serious experiential road bumps. She recently lost her father, is avoiding her mother and other family, is in denial about a dangerous alcohol dependence, has a shitty job correcting university entrance essays, and is living in the UK on an expired visa.

Mary’s decisions are increasingly suspect, her judgment poor, and her ability to take care of herself progressively ineffective. When we meet her she’s already suffered many a catastrophe, and it’s clear that the novel’s timeline is headed in a similar direction, yet Gardner gives Mary’s new tragedy a certain distinction from the others. Something about her fragility, something about her earnestness. Perhaps also because it seems that Mary’s other catastrophes happened to her while she wasn’t paying enough attention, and yet this recent mess is one she went searching for with purpose and blind dedication.

In terms of the writing particulars, the book is an interesting mix of pacing. On the one hand, Gardner uses a rapid-fire, nearly breathless style of narration, pushing the reader quickly through changes of setting and scene.

Halftimes and quarters. Commercial breaks. Mary slips to the loo. Wanders through the pub on her own. Jake is somewhere—in conversation with people he knows. He’s introduced her. She remembers this, vaguely.

Paused in corners. Standing near strangers, enormous men—red-faced and smiling. An overweight woman with peroxide blonde hair. Hideous orange carpet. Place filled with cigarette smoke, more bodies, blue jerseys. Pints everywhere. Bubbly ale in clear glass mugs, spilling over. The crowd at the bar. Bartenders pulling pint after pint.

This drive lends a lot of momentum to the story and helps give the novel its urban feel. People walk fast, talk fast, move from party to apartment and from bar to taxi. Conversations are often a rapid staccato, never lingering on difficult subjects, and often include verbal tics like “um” and “yeah” as well as a full range of expletives.

On the other hand, much of the novel is presented through emails and text messages between Mary and the man she is hoping to keep—a poet, struggling actor and young father named Jake. These are written out in full form, and include the lapses in grammar and embarrassing confessions a person might make in virtual communication (while most often inebriated).

yikes! I think I;m a little drunk. At this cool place on •oldham street. oh baby, wish you were here. These three guys are hitting on me. argh!

In the same way that Gardner’s dialogue is sometimes uncomfortably true-to-life, the emails and texts are also very raw, sometimes even embarrassing to read. But they work because they slow down the breathlessness of Gardner’s narration.

In the early chapters, these emails and texts have the potential to become a gimmick, or through overuse start to grate on the reader’s patience, but as Mary and Jake’s emails grow more daring and their in-person meetings devolve into partying, sex and middle-of-the-night confessions, this constant inclusion of their virtual relationship becomes an honest comment on the distance between Mary and Jake and their inability to actually speak face to face. Not to mention what it says about Mary and Jake’s world, contemporary with the majority of the novel’s audience, and the necessary negotiation of virtual and material that has become so common.

There’s an argument to be made for Sherry & Narcotics as a coming-of-age novel for Generation X. Mary is very much a member of that tribe—financially and geographically independent, at ease in the greater world, with more choices and possible connections than any of the previous generations, and yet, true to the Generation X crisis, slow to negotiate her way to emotional adulthood and at risk to the dangers of her precious independence.

That message certainly isn’t heavy-handed; it is subtly carried through the story. One of the greatest qualities of the novel is its velocity, how the reader can feel the energy of these months of Mary’s life, and obviously where they’re taking her. Head-first, eyes-closed into a concrete wall. When the impact occurs, it unrolls in a series of devastating scenes, one in particular which is difficult for the reader to live through alongside Mary. But Mary’s final catastrophe showcases Gardner’s skill for fast-paced fictional movement in an extremely powerful and unforgettable way.

+++