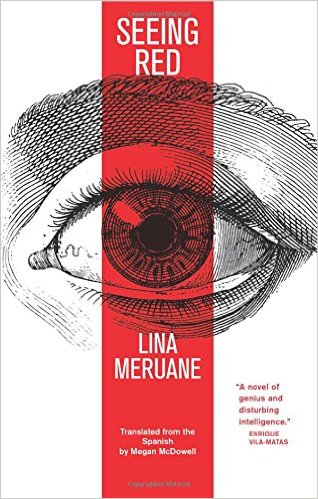

Deep Vellum, 2016

Lina Meruane’s autobiographical novel is intense, lyrical, unsettling, and hard to put down. It draws the reader into the rhythm of events, at times precipitous, at others excruciatingly slow. The novel portrays the aftermath of a stroke that leaves the narrator nearly blind. Meruane appears by name in the novel, explaining how she condensed Lucina to Lina. While the self-portrait is both intimate and painful, the narrator retains a certain reserve. The narrator is unsparing of herself, describing her sudden neediness and dependence, and her resentment of that need. Short-titled chapters structure the narrative, and entire chapters may be enclosed in parentheses, allowing for shifts in perspective. And while at times the narrative is directed toward an unidentified, abstract listener/reader, at others Lucina addresses a specific interlocutor, particularly her boyfriend Ignacio.

The action takes place in New York and in Chile; Lucina notes the ways she is an outsider in both places. The translator’s judicious choice to leave certain words or phrases in Spanish reminds the reader of the move between languages without becoming exotic or trite. The narrator’s enclosure feels claustrophobic at times, yet memory and appropriation (or imagination) of what others might have seen expands the horizon. Short allusions—“the hollowed silhouette of the two pulverized towers, the line of the mutilated sky”—situate the novel historically, without explicitly including dates. Lucina moves through spaces that are at once newly unfamiliar and yet known in great detail, as with the memorized map of Santiago that allows her to direct Ignacio through traffic. Says Lucina, “My memory’s visual laws dictated the landscape to me.”

The novel opens with a choppy burst of incomplete sentences, as the narrator traces the moment of hemorrhage, herself a spectator observing her own eyes. Lucina watches:

blood spilling out inside my eye. The most shockingly beautiful blood I have ever seen. The most outrageous. The most terrifying. The blood gushed, but only I could see it.

Outrageous, terrifying beauty returns throughout the novel—as in her creepy desire to caress Ignacio’s eyeballs. Lucina asks the impossible of Ignacio—patience; tedious, arduous personal care; perhaps even one of his own eyes. The possible precariousness—certainly newness—of that relationship appears in the description of Ignacio’s as “a voice so new in my life I sometimes take a second to recognize it.” Ignacio is long-suffering, irritable, demanding, generous; even in anger, some things remain unnamable. Asked to surrender an eye, Lucina recalls his response: “How could you even think I’m going to give you that, you said, without daring to name what I was asking for. Just that.”

McDowell’s word choices are sharp and evocative. She captures a sometimes halting, sometimes flowing rhythm that mimics the narrator’s fumbling steps as she begins to move, sightless, through the world. The narrative mirrors her resistance to bad news, her hope, denial, and confusion, and snares the reader in occasional eruptions of panic. The novel was published in Spanish with the title, Sangre en el ojo, the idiom, “tener sangre en el ojo,” meaning to bear a grudge. The English Seeing Red is spot on, carrying the sight of the blood in Lucina’s bleeding eyes as well as the fury of the person “seeing red.” As Lucina puts it early on, “liters of rage were clouding my vision.”

Lucina listens to books on tape and wonders if she will be able to write again. She describes her isolation from her doctoral program. Her thesis advisor asks after her writing—not just the thesis, but a novel in progress—and suggests dictating into a recorder. But for Lucina, “It wasn’t actual events that drove me, but rather words, and it was my hand that pushed the words, that built them up and then broke them down to forget the phrases again. Writing was a manual exercise, pure juggling. It would be easier to learn braille, which required fingers, than to try to work by ear.”

That awareness of words is present, too, in the comparison of accents, Lucina’s Chilean Spanish differing from Ignacio’s Galician, word choices changing geographically but also across time. When Ignacio visits Buenos Aires in the midst of the Argentine economic crisis, he spends every cent he has, wishing he could stop the collapse. Lucina challenges him:

You alone, with just some dollars? Like a second-rate conquistador with glass beads? Yes, yes, you’re right, I couldn’t think of anything else to do, he said, swallowing. I couldn’t help it, I went into stores like I was possessed and bought something, anything, it was all on sale, and the last thing I bought was this suitcase to carry all the gifts I was bringing you. I heard the sound of a cierrecler, a zipper, which Ignacio called a cremallera but some old Chileans with Arabic ancestry still called marruecos, and the metal teeth opened so Ignacio could take out all the clothes that had been ‘made in la pampa’.

Dialogue is often collapsed, unmarked, into a narrative passage, almost as if the lack of visual pointers in the narrator’s daily life extended to the page. In a section describing pre-operative preparations, titled “what eye?”, she hears:

Filipino voices with cutting accents. One asks me who I am, what my name is. I give my full name, I spell it out. My mother confirms that is the name I was baptized with. Ignacio verifies that it is written correctly. Someone else takes my arm and fastens on it a plastic bracelet that gives my prisoner’s alias. I get up, I sit down. It’s cold, I say, but now no one responds. Another voice intervenes. What is your name? it says. I hear typing while I answer, afraid of making a mistake. And then, any congenital illnesses? What medicines are you taking? How many hours since you’ve eaten? I don’t know and I don’t want to know. Did you go to the bathroom this morning? I hope so. What are they going to operate on? Which eye first? The voices change but the questions are always the same: Which eye will the doctor start with? With my mind’s eye.

That mind’s eye continually pushes the reader of Seeing Red to see what it sees. This is a novel in extreme close-up, describing the unseen. The ending is at once open-ended and decisive—just right.

+++

Lina Meruane is one of the most prominent and influential female voices in Chilean contemporary literature. A novelist, essayist, and cultural journalist, she is the author of a host of short stories that have appeared in various anthologies and magazines in Spanish, English, German and French. She has also published a collection of short stories, Las Infantas, as well as three novels: Póstuma, Cercada, and Fruta Podrida. She won the Anna Seghers Prize, awarded to her by the Akademie der Künste, in Berlin, Germany in 2011 for her entire body of written work. Meruane received the prestigious Mexican Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Prize in 2012 for Seeing Red. She received her PhD in Latin American Literature from New York University, where she currently serves as professor of World and Latin American Literature and Creative Writing. She also serves as editor of Brutas Editoras, an independent publishing house located in New York City, where she lives between trips back to Chile.

+

Megan McDowell has translated many modern and contemporary South American authors, including Alejandro Zambra, Arturo Fontaine, Carlos Busqued, Álvaro Bisama and Juan Emar. Her translations have been published in The New Yorker, McSweeney’s, Words Without Borders, Mandorla, and Vice, among others. www.meganmcdowelltranslation.com

+

Amalia Gladhart has published translations of two novels by Alicia Yánez Cossío, The Potbellied Virgin and Beyond the Islands, and of Trafalgar, by Angélica Gorodischer. Recent poems and short fiction appear in Eleven Eleven, Literal Latté, Necessary Fiction, and Cloudbank. She is Professor of Spanish at the University of Oregon.