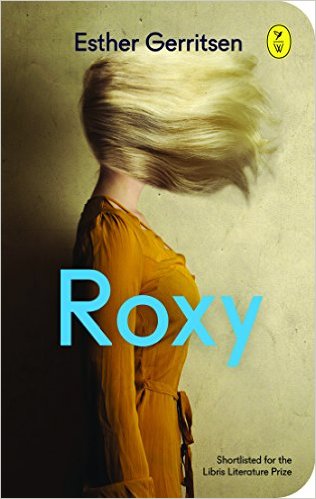

World Editions, 2016

Esther Gerritsen’s latest novel, her sixth in total and second to be translated into English, opens with a familiar scene. Late at night, a pair of police appear at Roxy’s doorstep to deliver a bit of bad news: her husband is dead. To complicate matters, he died along with a young woman who was both his intern and mistress. Roxy is devastated and she is left alone with her toddler daughter Louise, trying to salvage pieces of her broken life. The story that follows, however, is much less about loss and betrayal than it is about self-discovery.

Roxy, a moderately successful writer, is a young widow, only twenty-seven years old. Her husband Arthur, a famous film-maker, was much older. She ran away with him when she was just seventeen, and “has always known that she skipped something, took a short cut to adulthood.” In a sense, Roxy can be read as a sort of bildungsroman. While traditional bildungsromans, such as Jane Eyre or A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, begin with the protagonist’s early adolescence, Roxy is already an adult at the outset of the novel. Still, she has a lot of growing up to do, and so much of her identity is wrapped up in her husband’s life, that when he dies she must become almost an entirely new person. The near-endless possibilities are at once freeing and crippling. She can do anything, take her life in any direction, and at the same time she is frozen in place.

Roxy worries that she will not be a good mother to her daughter. She is afflicted by a recurring thought of suicide, which she refers to as “the fly,” and, at times, it is only the task of caring for Louise that keeps Roxy alive.

In order to move forward, Roxy is forced into closer contact with friends and family she has largely ignored throughout her marriage. There are her parents, with whom her relationship is rather fraught, thanks in large part to her debut novel, an autobiographical work “about a trucker who takes his thirteen-year-old daughter along with him during the school holidays so she doesn’t have to spend the summer with her alcoholic mother.” These parents visit, in theory to console Roxy and help take care of Louise, but with her mother drinking herself into a stupor each day, and her father touring the town and making friends at the local pubs, they only make matters more complicated.

Roxy’s two main companions are Liza and Jane, who she counts as friends, but who were also employees of her husband. Liza was the babysitter, and Jane his personal assistant. They are both kind and supportive of Roxy in the days following the accident, but Roxy finds herself questioning their motives. Do they genuinely care for her and Louise, or are they simply continuing on in service of their deceased employer? Or, even worse for Roxy to imagine, had one or both of these women been the object of her husband’s flirtatious, unfaithful habits?

Roxy finds forgiveness for her husband in the most unexpected way: in the arms of another man. Shortly after the funeral, she conjures an excuse to be visited by the undertaker, and quickly seduces him. Their lovemaking is frantic and carnal, clearly more a product of lust than love. Shortly before they finish, Roxy has a startling revelation about her husband: “She knows him now; they have a common history and she understands that Arthur wasn’t able to do without this. She loves him again.”

Yet this tryst isn’t all about reconciliation. That undertaker is not a single man. He has a wife and children of his own. When the affair is made public, Roxy shows a frustrating lack of sympathy or regret for having ruined his marriage. This is the first in a series of impulsive, destructive actions that Roxy undertakes. She drinks almost as heavily as her mother, carouses like her father, and takes the company of a few anonymous sexual partners. In the heat of an argument with Liza and Jane, she races on the highway at audacious speeds, causing her daughter to cry out in fear. Roxy attempts to comfort Louise by saying, “Racing is fun, sweetie.” In the process of this reckless streak, Roxy realizes she is capable of more than she ever realized, for better and for worse. Late in the novel, confronted by the consequences of her actions, she feels sickened. “Roxy wants to throw up. She retches. It’s no use. She’ll have to live with everything that’s inside of her.”

Roxy is the second novel of Gerritsen’s translated by Michele Hutchison, who does an excellent job capturing the heavy emotional tone of the novel in straightforward, uncomplicated language. American readers may find Gerritsen’s concise, lucid style similar to that of Laura van den Berg. Roxy never feels rushed or convoluted, as is sometimes the case with such short novels. Instead Gerritsen operates as a clear-eyed guide on Roxy’s tumultuous journey of self-discovery, delivering a powerful, immersive experience.

+++

Esther Gerritsen (the Netherlands) is an established novelist and playwright. Her successful novel Craving was published in English last year and shortlisted for the Vondel Prize. Roxy was nominated for the Dutch Libris Literature Prize and film rights have been sold.

+

Michele Hutchison (UK) was born on exactly the same day as Esther Gerritsen. She studied at UEA, Cambridge, and Lyon universities and worked as an editor for a number of years before becoming a literary translator. Recent translations include Fortunate Slaves by Tom Lanoye, La Superba by Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer, and Cravings by Esther Gerritsen. @M_Hutchison

+

Thomas Michael Duncan writes fiction, fact, opinion, and the occasional bit of nonsense. A recent escapee of upstate New York, he lives in Lexington, South Carolina. You can haunt him on twitter @ThomasMDuncan.