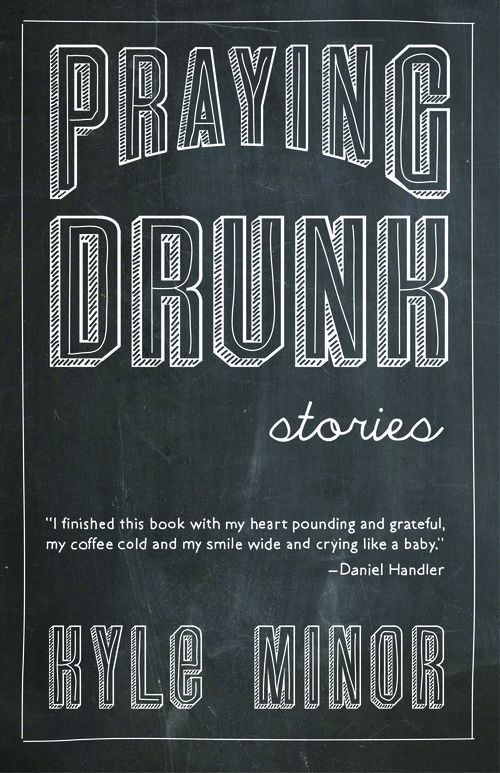

Sarabande Books, 2014

Kyle Minor’s Praying Drunk has been building steam for months, ever since its publication announcement in 2013. Minor’s previous collection, In the Devil’s Territory, (2008) was, like this new one, challenging, but not in the sense of experimental or perplexing: his work includes a variety of times, shifts, and psychologies. Praying Drunk moves from the southern United States to Haiti, and explores the lives of musicians and missionaries, and uniquely rendered explorations of suicide, religion, and coming of age, to name just a few. It’s a book that succeeds on the strength of its beautiful prose, excellent characters, and emotional honesty.

These stories are not explicitly interconnected, except for two pieces that are returned to later in the book, but it opens with a stern requirement: “These stories are meant to be read in order. This is a book, not just a collection. DON’T SKIP AROUND.” This might, as it did for me, make a reader focus on explicit connections between the tales, and while there are some common threads, they stand alone. However, there’s a joy within the unfolding narratives. By taking the book from beginning to end, the reader follows a trajectory that might not be immediately apparent, but ebbs and flows carefully. It opens with the perfectly titled “The Question of Where We Begin,” a story concerning a suicide. Given the emphasis on continuity, the touching, uneasy beginning can be viewed as a question of storytelling. The narrator traces the gruesome act backward from the end, hypothesizing on a sort of sociological Chaos Theory. Minor’s prose is careful. The following passage highlights the narrative movement, which has the potential to be redundant, but works to illuminate the questions that anyone asks in the immediate aftermath of personal tragedy.

What if his mother and father had never met and married at all? What if sperm and egg had never met? Or what if sex was not, as my grandmother once asserted, a nasty thing forced upon her in the night, but rather a thing of love and passion? Or what if something had been different in Owensboro, Kentucky, where they met in a roadhouse? What if the idea of love somehow transformed my grandfather into a man who could declare that for his seventeen-year-old bride and their children-to-be, he would never touch the bottle again? If we change a variable here and there, my uncle doesn’t lock the doors, lie down on his bed, stick the pistol in his mouth, and blow his brains out.

Minor served as a preacher before his emergence as a writer. Religious questions weigh heavily within Praying Drunk, but these are handled in various ways, all of them believable within the plots. If a character struggles with belief, or is firmly within the confines of fundamentalism, Minor has the authority to handle all sides. Without making too many assumptions, his writing is influenced by his life: he’s explored religious and secular worlds, and no matter what a given reader believes, the spiritual questions and observations are written to show, at the very least, how the cultural and psychological influence of religion can infuse, highlight, and infect anyone’s daily life. The twelve year-old narrator of “You Shall Go Out with Joy and Be Led Forth With Peace” represents a strong balance of fervor and reality. He wants to be a good Christian, yet struggles with bullying and contradictions. Minor is able to include obvious religious symbolism that would be out of place within other texts, but it works because he’s not trying to be sly or pull a fast one. The imagery is key to the narrator’s worldview.

I am twelve years old, standing beneath the starfruit tree, pos-sessing this terrible knowledge . . . and yet, and yet, above me are starfruit, a great many, and I have been picking them for all the years I have gone to this school, ever since I was four years old, and I know how to pick one that is sweet enough but not overripe, and not overly bitter, either. It is truly amazing to me that I am the only person I know, student or teacher, who picks from this tree.

“There Is Nothing But Sadness in Nashville” is one of the strongest pieces within the collection, and highlights Minor’s ability to explore multiple issues within the structure of a family drama. A brother goes from work as a musician to “honest labor” and back again, with various family members concerned about his well-being. Minor gets into the emotional turmoil by using run-on sentences, an aesthetic tool used to great effect by David Foster Wallace, but done in Minor’s own way:

For a while my brother stops calling so often, and I worry he’s sinking into some dark hole he can’t get out of, all those long hours of guitar practice upstairs in his bedroom all through junior high and high school, and all those hours, days, weeks, months, years, by now almost a decade cramped in shitty band vans, logging miles, losing sleep, playing shows for thirteen or thirteen thousand, all of it wasted now, and him locked into some blue-collar management slave life not unlike what we watched our dad do all those years among air-conditioning men and sheet-metal men before he went back to college and clawed and scratched his way up to the corporate life, the desk and the dictaphone. My brother calls and says that’s the kind of thing that sounds good to him now, the desk and the secretary and the screaming boss and the health insurance plan, HMO or PPO, I care not which. I want to go home, he says, and watch TV and chop vegetables like Emeril Lagasse and melt butter and sprinkle garlic on top.

The breadth of Praying Drunk highlights the unspoken understanding that no review can truly do complete justice to a complex work. A previous review in Publisher’s Weekly called the layout distracting, but it all depends on a reader’s expectations. Someone new to Minor’s style might be taken aback, since some of the Q&A sections hint at autobiographical influences, and therefore one might be too tempted to view some of the passages as veiled reality, not straightforward fiction. It’s pointless to compare Praying Drunk to In the Devil’s Territory, but this is a nod to both collections: both have their own worlds and missions, and ultimately set themselves apart as different works of art. Given his strengths, the next logical step for Minor could be a standalone novel. But his stories, both individual and collected, are just as satisfying as a single, full-length narrative. Minor’s creations are novelistic in their ambition, and it’s only upon completion that one realizes how much has been packed into the span of a few pages. This book requires patience and future re-reading, but reads as a wonderful balance of storytelling and cultural examinations. Minor doesn’t judge or moralize his characters’ shortcomings, but shows the complexity and gray areas that go into choices and setbacks.

+++

+