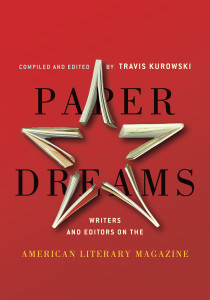

Atticus Books, 2013

I am guilty of taking history for granted. When I drive, I offer no thought to the workings of the internal combustion engine. I don’t consider Ford’s assembly line or the social impact of the Model T. I don’t contemplate the intricate evolution that has deposited me in a vehicle that is absolutely space age compared to the cars of my youth. Unfortunately, this kind of perspective, the selfish intersection of the here-and-now and my own needs and wants, isn’t limited to automobiles. Deep histories, full of secrets and forgotten tides, surround us, and learning them leaves me humbled, my focus opened a degree wider.

A confession: I’m a geek for literary magazines. The thrill of holding a journal I love that contains one of my pieces rivals that of holding my latest novel or collection. Part of this is selfish—publication in a literary journal doesn’t entail the non-writing work a book release does. There are no blurbs to gather, no review copies to send out, no appearances or interviews to line up. But the joy of a piece appearing in a lit journal runs deeper than convenience. Seeing one’s work in a fine publication heightens a sense of community, a feeling often lost in the solitary process of writing. A story or essay or poem, crafted alone at a writing desk, is suddenly surrounded by the work of one’s peers, voices familiar and not. Opening an envelope and holding a journal takes one back, an echoing through the years of what first called one to this pursuit. We all once dreamed of first publication, and when we hold a new journal, we’re reunited with that dream, with that walking-on-air elation of achieving, of belonging. It’s like remembering the first kiss of a lifelong love.

Paper Dreams, published by Atticus Books and edited by Travis Kurowski, is an examination of the modern American literary magazine. The book is thick and beautiful, its component pieces lovingly culled and arranged. The project originally began as a 2008 issue of the esteemed Mississippi Review edited by Kurowski and Gary Percesepe, but that issue, as fine as it was, was simply a starting point for Kurowski’s greater exploration.

Paper Dreams is well served by its structure. It is divided into sections devoted to literary movements and individual decades; to discussions of past, present, and future. Kurowski takes us from the perspective of editors to contributors; from journals that have run for decades to ones that have risen, shone brightly, then faded. There are examinations of the changes in medium—from the post-WW2 mimeo revolution to the print versus online debate that arose fifty years later. This structure lends the book one of its most appealing elements—its deep-focus examination of history. The lit scene is important to me—as I assume it is to those readers taking the time to read this—and at the heart of that scene are literary journals and indie presses. I cherish these magazines for what they give me now; their currencies of art and daring, a greater voice I want to be a part of. Paper Dreams takes my self-centered view of lit journals of the present and what they mean to me and gives it a shake. Kurowski turns me back through the years and shows me history; shows me a wild, furry heart whose DIY ethos will continue to beat beneath this scene long after I am gone and forgotten.

Paper Dreams is full of wonderful stories and currents. One of my favorite parts of the book was the section “Writers on Lit Mags.” Folks like T. C. Boyle, Rick Moody, Jane Armstrong, Laura van den Berg, and others, offer short, personal stories of their experiences as editors and young writers. These pieces—sometimes humorous, sometimes touching, always entertaining—provide first-hand accounts of journeys into our little literary realm. Something I found particularly fascinating was Kurowski’s use of older reflections on the state of the literary magazine. This device lends the book a deeper touch—a living history, if you will—the sound of voices and perspectives once current but which the reader can now consider under the lens of passed time. Essays from nearly every decade of the book’s 100-year focus provide a valuable platform for observing and understanding the evolution of the literary magazine in the context of its time.

Certain stories in Paper Dreams will stick with me—the fascinating tale of Jane Heap and Margret Anderson, the editors of the Little Review and their arrest for publishing excerpts from Ulysses; the story of Assembling, a magazine I’d never heard of but which had a fascinating life and death; a 1997 email exchange between Ralph Lombreglia and Frederick Barthelme on the then-looming future of web publishing (a conversation which would qualify as prophetic, given that it is still relevant today). But while these individual pieces will stick out, the greater gift I will carry from reading Paper Dreams will be the depth of appreciation and understanding it provided. Paper Dreams is nothing less than a celebration of this greater, living movement that we are fortunate to be a part of, and I, for one, feel richer for understanding so much more than I did before.

+++

Editor Travis Kurowski teaches creative writing and publishing at York College of Pennsylvania. He is founding editor of Luna Park, soliciting editor for Opium Magazine, and Literary MagNet columnist for Poets & Writers. His writing has recently appeared in Little Star, Armchair/Shotgun, The Lumberyard, Mississippi Review, Hobart and > Kill Author. Paper Dreams is his first book.

+

Curtis Smith’s most recent books are Witness, an essay collection from Sunnyoutside, and Beasts and Men, a story collection from Press 53. His next novel, Lovepain, will be released by Aqueous Books in 2015. Visit him at www.curtisjsmith.com.