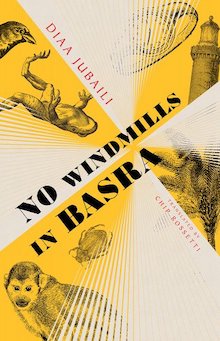

translated by Chip Rossetti

Deep Vellum, 2022

In describing No Windmills in Basra by Diaa Jubaili, translated from Arabic by Chip Rossetti, it’s tempting simply to list the fantastic: stars cascade out of a woman’s hair; a lark searches for disappearing dimples; a boy oozes salt from his pores, an excrescence “his aunts on his mother’s side would have preferred it were diamonds.” Leave it up to your family to bring you back down to earth. The seventy-six pieces in the book wittily embed fantasy within difficult realities, particularly that of contemporary Basra.

Jubaili is an Iraqi writer, but it may be more accurate to say that he is a writer from Basra, the city in southern Iraq where he grew up and still lives, and which provides the setting for almost every story in the book. In a 2016 interview with Comma Press, Jubaili described Basra as “a city of narration…a city of poetry,” consistent with its position as a cultural capital in Iraq. At the same time, as Jubaili explains, Basra’s location near Iran, its targeting during America’s wars in 1991 and 2003 and in the Iraq-Iran war of the 1980s, and its present exploitation by foreign energy companies and domestic religious extremists, make it a place where writers like Jubaili “write to resist the misery that has befallen the city.”

As Rossetti points out in the introduction, Jubaili’s stories draw on Arabic folktales, and they share certain characteristics of folktales—the romantic but eerie sense of magic in our world, the placement of archetypal characters within localized settings. The stories are also very short, and they huddle up beside one another like candy bars in the checkout line. Visually, the pieces are reminiscent of laid-out lyric poetry. The effect is something between a sonnet and a sigh. What’s interesting is how Jubaili summons the force of language in so little space. In one page-long story, two lovers “came up with a new way of communicating … Each of them tattooed the shape of the other on their arm, and whenever one yearned for their beloved, they scratched the tattoo.” Lovers with matching tattoos is nothing new, but it’s the unexpected scratch that gets you; Jubaili creates a friction between the lovers and the readers at the same time.

Jubaili’s brevity gives the illusion of simplicity, as do his often solitary characters. When several characters appear, they relate to each other seemingly straightforwardly—a son and a mother, a pair of lovers, a coach and a struggling soccer player. The stories often resolve with a twist or revelation. Although not written to be edifying, they can seem like magical parables. But they avoid being obviously didactic with a style that is sly and self-aware. “Departing from habit, Burhan stuck his hands in his pants pockets, the way lovers do in the movies and love stories,” Jubaili writes of a character in the midst of his own love story. Jubaili’s use of irony, like the stories themselves, does a lot with a little. These quick, mischievous narratives allow Jubaili to create world after world in Basra without being ponderous or seeming to exploit the real difficulties of life there.

Like the stories themselves, Jubaili’s characters use fantasy both to resist and to document the tragedies of the region. In the opening story, “Flying,” a man named Mubarak modestly jokes of being a “flying soldier” during the 1991 Gulf War. He was flying because an American bomb hit his vehicle and threw him in the air. He survives and, later in life, gets a job as a security guard at a poultry plant. It too is hit by an American bomb, this time in the second Iraq war, in 2003. Somehow, he survives again, emerging bloody and covered in chicken feathers, “staggering left and right, flapping his arms like wings.” As readers, how do we see Mubarak? Is he a symbol? A survivor? Another victim of America’s unchecked militarism? The tale’s final words offer a simpler conclusion, one that is so absurd that it must be real: “He was flying. Flying.”

+++

Diaa Jubaili was born in 1977 in Basra, Iraq, where he still lives. He is the award-winning author of eight novels and three short story collections. No Windmills in Basra won the Almultaqa Prize for the Short Story. He was a contributor to the short story collection Iraq +100 and has written for The Guardian.

+

Chip Rossetti has a Ph.D. in modern Arabic literature from the University of Pennsylvania. His published translations include the novel Beirut, Beirut by Sonallah Ibrahim; the graphic novel Metro: A Story of Cairo by Magdy El Shafee; and Utopia by Ahmed Khaled Towfik. His translations have also appeared in Asymptote, The White Review, Banipal, and Words Without Borders. He has worked in book publishing for over twenty years, and is currently the Editorial Director for the Library of Arabic Literature at New York University Press.

+

Carr Harkrader is a writer and book critic in Chicago. His writing has appeared in INDY Week, South Side Weekly, and the Washington Independent Review of Books. You can follow him at @CarrHarkrader.