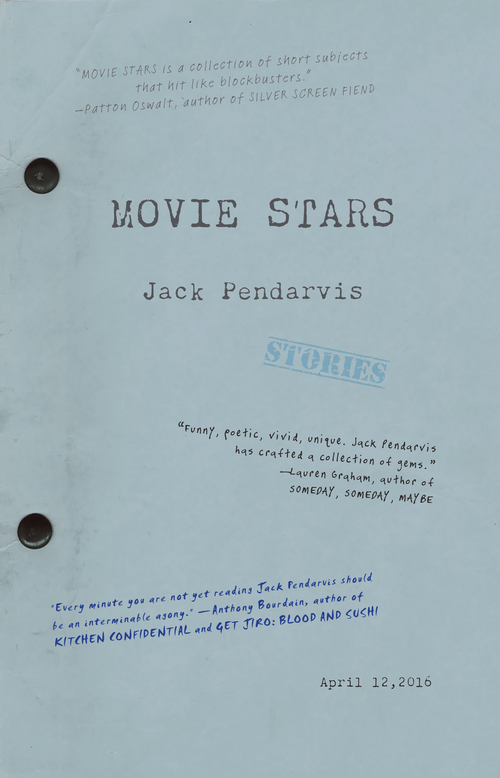

Dzanc Books, 2016

The characters in Jack Pendarvis’s short story collection Movie Stars laugh frequently, even in moments of pain and disquiet. In “Duck Call Gang,” the narrator and his wife wake up in the midst of a violent thunderstorm, screaming in terror, then erupt into laughter. But long after his wife falls asleep he lies awake wracked with anxiety. In “Ghost College,” a struggling writer named Cookie is awarded a residency in a former doll hospital where a grisly murder once took place. But Pendarvis’s interest lies more in existential than supernatural horrors; Cookie, who moonlights as a copywriter for a pie company, accuses himself of hackery and his proclivity for self-flagellation ultimately alienates his wife. The timbre of a recurring in-joke turns cold and buried resentments arise:

“It’s like I don’t even know you,” Cookie said.

They laughed. It was one of their standard lines. But they stopped laughing sooner than usual. Then they changed the subject to why she had started buying unscented antiperspirant for them. Cookie could never remember whether or not he had put it on.

In “Frosting Mother’s Hair,” soft-drink magnate Tom bristles at the unseemliness of the oft-told tale of his parents’ honeymoon night (in which his mother imbibes ten Tom Collinses):

Had his mother even been conscious during Tom’s conception? His father would have been cold sober. This was the implication of the story that no one seemed to consider amid the merriment of the Thanksgiving table.

Such scenes demonstrate Pendarvis’s adeptness of tone; his writing is not hilarious in addition to being deeply affecting but rather both simultaneously. With insight and compassion, he reveals the melancholy that so often underlies humor.

The book is populated by delusional eccentrics whose ambition and yearning inevitably lead to social catastrophe. In “Your Cat Can Be a Movie Star!” the first-person narrator is bilked out of three hundred dollars by a bartender who promises to use his dubious connections to secure the narrator’s cat a spot amongst Hollywood’s animal elite. Like Twain, Lardner, and Portis before him, Pendarvis excels at crafting voices whose naiveté provides unusual opportunities for comedy and pathos. The unnecessarily self-defensive narrator of “Movie Star” speaks directly to the reader in a cliché- and malapropism-riddled discourse reminiscent of a crazed internet commentator. But Pendarvis renders this hapless protagonist more human than clown. His monologue frequently skirts right up to the line of soul-shattering self-awareness. At one point he complains:

We are always going around criticizing St. Peter for denying Jesus thrice before the crowing of the cock but come on! It is so easy to want to ‘go with the crowd’ who happens to be around. We all just want to fit in.

The profundity of his loneliness is more deeply felt for its tragic inarticulateness.

Pendarvis is a master of what might be called eloquent imprecision, a counterpoint to the writing textbook paradigm that specific, concrete details make for the most effective fiction. A man’s apology to a server for leaving a bar without having ordered anything is depicted thusly: “He said consoling things.” Later he becomes “flooded with feelings” while contemplating the fluid nature of time. This haziness of description is perfectly in line with Pendarvis’s characters, who can’t make sense of themselves or articulate the motivations behind their frequently self-destructive whims. In one story, a leather jacket is described vaguely as having “numerous attachments.” To specify exactly what those attachments are would undermine the jacket’s totemic significance; it’s an absurd and sad expression of individuality in a world in which no one cares to ask what the attachments are.

When Pendarvis get specific, he does so with a keen eye for objects that reflect the discomfiture of his characters: tacky brown balloons that decorate an open house, glitter falling upon a “sad cake in the dark” at a strip club birthday party, hair “the color of a gravestone rubbing with a No. 2 pencil.” The often streamlined prose belies an almost academic interest in the irrationality of language. One character muses on the contradiction of his hotel’s Business Center: “It was some closet with a tiny wastebasket and a computer.” Given that language is so essentially deceptive, what hope do Pendarvis’s outcasts have of conveying their alienation?

The stories of Movie Stars are structurally idiosyncratic. Pendarvis doesn’t flinch at breaking rules for writing short stories. Voice, gesture, and accretion of detail are the elements of fiction that matter here. Let the plots meander and the narrators digress. Scenes and riffs go on two or three beats longer than the reader expects, to effects both amusing and tender. The narrator of “Jerry Lewis” flirts with a neighbor and observes:

She laughed like a sexy crow. The way she talked was also like a sexy crow, one of those crows that can talk. But sexy.

The best story in this exceedingly strong collection, “Cancel My Reservations,” follows Chuck to Los Angeles with the aim of winning at auction a Bob Hope artifact for a friend he believes is dying. It switches to that incidental character’s point of view very briefly before returning to Chuck’s for the remainder of the narrative. The reader understands the futility of Chuck’s journey; his friend would rather lie about having a fatal disease than withstand any more of Chuck’s Facebook blathering. Forget about plot, this story teaches us: focus on incident. The concluding image, of Chuck “with his greedy fist around a black plastic fork, cramming an entire serving of macaroni and cheese into his mouth at once,” is a heartbreaking depiction of the essential sadness of the human condition.

Yet in the face of such ugly truths what else can Pendarvis’s characters and readers do but laugh? Despite its title, Movie Stars is far more concerned with such revelations of striking vulnerability than indulging in superficial Hollywood glamour. Hilarious, dark, and humane, Movie Stars may leave the reader in awe.

+++

Jack Pendarvis is the author of three previous books of fiction and one of nonfiction. A former columnist for both the Oxford American and The Believer, he is a writer and story editor for the Peabody award-winning television show Adventure Time. He lives in Oxford, MS.

+

Luke Geddes is the author of I Am a Magical Teenage Princess, which Publishers Weekly called “a rewarding and unusual collection.” His work has appeared in Washington Square, Mid-American Review, Hayden’s Ferry Review, The Comics Journal, and other venues. He tweets sporadically at @neurosescatalog.