CCLaP Publishing, 2013

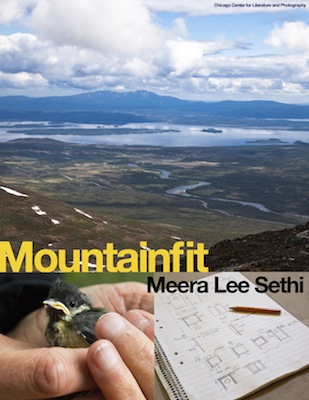

In the summer of 2011, science writer Meera Lee Sethi, who was then based in Chicago, spent nine weeks as a volunteer field assistant at Ånnsjöns Fågelstation, a bird observatory located in the mountains of Jämtland in Sweden. In the collection of seventeen short natural history essays that came out of that experience, Mountainfit, Sethi helps track birds small and large, from songbirds that fit in the palm of your hand to enormous gyrfalcons with four-and-a-half-foot wingspans. She checks nest boxes. She radio-tracks birds that have been tagged with a transmitter—which means hiking cross-country wearing a headset, with a receiver slung around your neck and an antenna in your hands, following the signal wherever it leads. This work, with its demand that the tracker listen to terrain, is ultimately what brings her to feel adapted to this place—that is, “mountainfit.”

This book about fieldwork begins not with data but with language. The first Swedish word in Mountainfit, spoken by the field assistant who meets her at the Stockholm train station, is the name of a bird, rödvinge, redwing thrush. Unfamiliar land and species, unfamiliar language: the birds of Sweden are twice foreign to Sethi. Mountainfit includes an appendix that lists birds mentioned in the book by their English and Swedish common names and then by their Latin scientific names, in the system of binomial nomenclature developed by the Swedish scientist Linnaeus in the mid-1700s; though Linnaeus doesn’t make an appearance in the book, his presence hovers here, as he was the one who first classified many, if not all, of the Swedish birds that Sethi encounters. The fact that this science writer doesn’t rely on Latin as a common language, doesn’t say Turdus iliacus when she means redwing thrush or her fellow field assistant means rödvinge, suggests the extent to which language is the lens through which we see the world. (This can lead to humor, as when Sethi grapples with the possibility that werewolves roam the mountains of Sweden—until her companion corrects his English and clarifies that he is talking about wolverines.) In Mountainfit, human speech is part of our own natural history, akin to birdsong.

Ulla’s speech is scattered with utterances of kanske (‘perhaps’). Most of the time I don’t understand what comes in between, and experience each instance of it as a little wave breaking: kan-shuh, shuh, shuh.

You can sense the attention Sethi pays to the human world in that passage, and her attention to the natural world in her description of the croak of a brambling, a kind of finch, which “abrades the air—like a saw going through wood.” Did you think that lemmings were small, meek creatures? Sethi will set you straight, describing one she startles as “a blur of tiny teeth and claws and shrieking.” While there are occasional lapses in the writing, such as repetition in phrasing—mosquitoes that are the “most gigantic mosquitoes I’ve ever seen,” a curlew’s cry that is “the most charming public siren system I have ever heard”—overall this is a book of scrupulous observation.

The most honest moment may be this one:

Between its swift and graceful sallies downward, the silvertärna [arctic tern] hovers not (as I write on a postcard, and then later regret) like a hummingbird …

—and here Sethi draws the reader into her revision, an attitude toward seeing and writing that fits with her depiction of science as collaboration. No single observation is enough; no individual is privy to the whole story. Knowledge is gained over months, years, and global terrain. Technology helps. A device such as the geolocator (aka light logger), with a sensor that “captures measurements of ambient light levels at predetermined intervals, timestamps them, and stores the data in a memory chip,” enables scientists to determine the times of sunrise and sunset, and thus a migratory bird’s location on the planet, to an accuracy of about 150 kilometers. But technology doesn’t do all the work. Sethi takes us to one end of a bird’s migration and her own part to play: the human who slogs across marsh and mountainside to retrieve the geolocator and its data.

Some of Sethi’s briefest essays seem like literary cousins to the micro-essays of Charles Finn, whose Wild Delicate Seconds: 29 Wildlife Encounters came out in 2012 from Oregon State University Press. What Sethi and Finn have in common is the way their short-form writing captures the nature of human attention.

Science is not the only activity going on here. In Mountainfit, birds and birdsong, human nature and human language come together in mythology, as Sethi recounts the numerous myths and legends in which the language of birds brings knowledge to humans. While acknowledging the appeal of these ancient stories, she also dismisses them tartly: “No myth is half as astonishing as the facts collected in a single ornithology textbook or field study.” And yet Sethi believes in astonishment. She writes,

I touch a finger to the azure head of a blue tit … and watch its feathers part when Stefan blows against its belly to check for fat below its filmy, wrinkled skin.

The idea of myth reminds me of Frederick Turner’s observation, in In the Land of Temple Caves (Counterpoint, 2004), his account of visiting the Paleolithic painted caves in France, that “In our time the very term ‘myth,’ which once meant Beautiful Truth, now signifies that which has been exposed as a falsehood.” In Turner’s account, the humans of ten or twenty thousand years ago were in contact with the animals they painted—mammoths, horses—in a way that has long since been lost. How many readers of this book, like Sethi herself in her urban life, do not see wild creatures up close? As her words breathe other meanings into moments of scientific observation, her writing returns us to the origins of myth, to what happens when humans meet birds.

+++

+