You, too, can turn trouble around and become a small god. So says the fictional science (31).

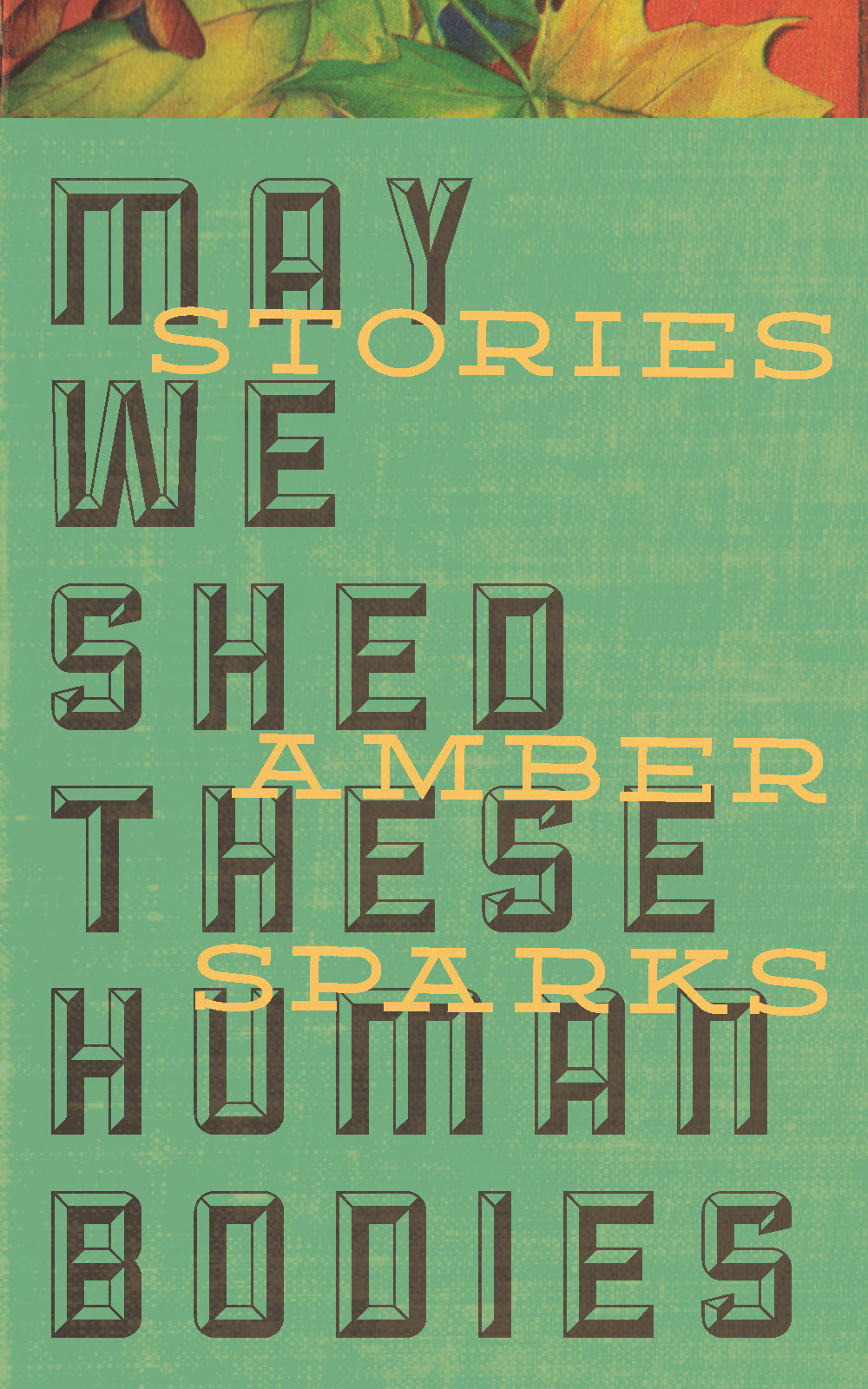

Curbside Splendor, 2012

Amber Sparks does not write science fiction; rather, she writes inventively about the truths of our world in a style that often parallels humor with sadness, death with life, and optimism with doubt. The thirty stories comprising her debut collection, May We Shed These Human Bodies, portray a perspective of life unseen throughout much of contemporary fiction and make a strong case for Sparks as one of contemporary fiction’s true mad scientists. At turns magical, fable-like, and realistic, her stories crackle with imagination yet never shy away from emotional intensity or artistic integrity. But above all of the collection’s achievements, Sparks’s most triumphant accomplishment comes from her ability to harness an artist’s objective. Story is her platform and within yields great rewards. Take “Study for the New Fictional Science,” which includes the line that may act as the thesis for the entire collection:

You can create a world that promises love for those who shine and pride for those who fight and a story that lives on, for those who understand the imaginary costs (31).

There’s not another line more befitting to describe Sparks’s collection; the world she creates challenges as much as it rewards, and for those who do understand the imaginary costs she speaks of, May We Shed These Human Bodies will continually impart the sort of wisdom the only great art can.

As far as typical narratives go, Sparks eschews the ordinary in favor of the uncharacteristic, and the results reveal a style that favors less emphasis on character and more on establishing theme. The title story introduces a cluster of trees as a narrator, and they begin their tale by suggesting their nearly harmonious existence:

We were good at being trees, long ago. We had been years with our knots, tallying the rains and dry spells with careful accuracy. We shared conversation with the wind, the squirrels, the spiders. We shared quiet with the clouds before they burst.

We were good to look at, too; we were tall trees, well-grown. We stood eighty feet high and three feet around, our bark a flat, glassy gray, a few fissures mapping our journey through seasons. In the winter, our buds were the color of coffee, dark brown and velvety, and each spring we exploded in green. The animals walked our branches, the breezes pushed at our leaves, and the wind helicoptered our seeds to bury almost-trees in the earth.

We were experts at being trees. We still had a hundred good years left, and we weren’t interested in being anything else. (54)

And yet, this idyllic life is lost when three men—known only as “the Three”—wander into the forest and question the trees about becoming humans. Despite the trees’ reluctance, the men forge ahead and, without warning, transform the trees into their new bodies: “Then, we were new things, human things. People” (54). Confined to their new bodies, the trees long for their tranquil past, and as the story concludes, the trees, now in their human bodies, find that they wish to discard their human qualities:

We are not good at being men. We are weak, our minds and bodies soft and pliable, our histories marred by violence and loss into unsteady seasons (55).

The implication here and elsewhere in the collection is that of the darkness that shapes humanity’s decisions, which is not to say Sparks doesn’t show anything resembling hope in these stories. More often than not, however, Sparks appears more interested in forcing the uneasy questions than providing uncomplicated answers. In “The Chemistry of Objects,” she reviews several chemically created items throughout history designed to kill:

Like Frankenstein, we become dangerous makers. Our hearts lean toward what burns in nature, and whether for pleasure or profit, through accident or malice, we create best what kills best. And try as we might, we cannot seem to climb out of this paradox. We are monkeys with test tubes, apes at the evolutionary table (28).

Such a story doesn’t shy away from presenting humanity’s past atrocities as they truly transpired, and it points to humanity’s inability to learn from such atrocities. While Sparks does introduce readers to characters late in the story, “The Chemistry of Objects,” like many of the stories in the collection, seems determined to be a story not about any one particular person but rather a story about humankind, and such an effect reveals Sparks to be a writer with a great eye for universal concerns.

The failures of humanity might perhaps lead Sparks to realize more hopeful scenarios, and in “Feral Children: A Collective History,” she envisions a world where children leave home to be raised in the wild. The wildness suggested in such an act serves to evoke the sense of youthful abandon, and despite this sense of recklessness, at some point, these children will grow:

Their animal speech is accented, a reminder that these children will not stay wild forever. Not wild and free like wind like biting like galloping and snorting and swimming and nuzzling and guzzling and piling up together in good raw wet fur smells forever (104).

The language is impressive here, yet Sparks knows that the child will one day turn into an adult, possibly the same kind of adult bent on destruction. The hopefulness in such a story comes late, but it does come in the parting lines of the story. Despite adulthood and the pains that come with it, there will always be some wildness left behind:

…there will be only a still-wild, feckless, fettered child left standing at the edge of the map, ready to push the human race into something as uncharted as it will always be (105).

That lasting image hints at something magnificent; despite the horrors present in the world, the wild heart of a child lives on.

May We Shed These Human Bodies draws to a close by echoing the parting sentiment found in “Feral Children” with “The Only Story in the World,” one of Sparks’s more touching stories. Broken into sections that first begin by focusing on the core of a family (father, mother, child) before expanding outwards (heart, land, war), the story speaks universally of mankind and its imperfections. Speaking to the child introduced at the onset of the story,

The heart said, Child, you will wander the world and bring happiness to all you meet, and the world will make you its favorite daughter. But even you must come to an end. And this is the terrible prophecy that we hold close and secret. This is the always-whisper in our ear (138).

The line is one of Sparks’s most personal and beautiful as well as devastating. It acknowledges the truth of the world in such a matter of fact fashion that it’s difficult at first to recognize where the majesty of such a line exists, and yet, we know that it’s there. Such is the magic of Amber Sparks’s fiction.

+++

+