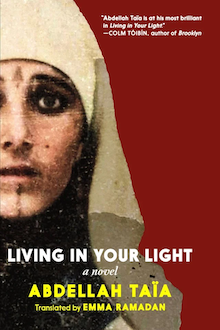

Seven Stories Press, 2025

A slim novel in three parts, Living in Your Light centers on Malika, an indomitable Moroccan woman modeled on the author’s mother. Visiting the souk with her father at Béni-Mallal, south of Rabat, in the mid-1950s, seventeen-year-old Malika falls headlong in love with Allal, the son of a distant relative. Her father leaves the pair to get acquainted over donuts. “I eat the donuts very slowly,” she says, remembering. “I take my time. I let you look at me all you want. My body. My character. My history. I am strong. That is what you will love about me. A strong woman who engulfs you entirely.”

Malika is not kidding about her strength, which is tested many times in these pages. Within a few years of their marriage, Allal joins the French army to make money and is killed while fighting in distant Indochina. The situation is sharply ironic: Allal is fighting for the French in a colonial war, yet he detests his French employers, who of course have also colonized his native Morocco. The loss of Allal haunts Malika, just as the violence of colonialism haunts them both. Yet she remarries and raises her children in a small house on the grounds of Rabat’s National Library where her husband is employed. Later she moves to Salé, where her strength is tested again when she is confronted in her home by a hostile intruder whose history eerily echoes her own.

Malika is magnetic, forceful, altogether wonderful—but then, all of Taïa’s characters are compelling, with complex inner lives. Unsurprisingly given Taïa’s stature as the first openly gay Moroccan writer, queerness is a theme throughout, and Taïa vividly portrays the pain of being either extremely carefully invisible or altogether too well understood and subject to violent repression. In contrast to the stark binaries of homophobia, personal relationships are complicated, particular, at once more ordinary and forgiving. When Allal brings Malika into his ongoing relationship with another man named Merzougue, Malika experiences this as a deepening of a relationship with a person she already loves. Merzougue, who “was here long before me,” is a man “whose eyes are always full of tenderness,” she says, and “when he looks at me his eyes don’t change.” After Allal dies, Merzougue and Malika join in grief to consecrate his memory in the mausoleum where the men used to make love.

The night in the mausoleum is just one of many indelible scenes. As newlyweds, Malika and Allal hiked regularly to a monumental waterfall. Malika recalls one of those hikes: “There was snow everywhere, everywhere. On the roads. On the fields. On the roofs of houses. On the trees and on the Atlas Mountains all around us.” The isolation and majesty intensify their togetherness: “I am with you in the white silence of the world,” she says, addressing herself to the memory of Allal. “We are below the falls now. So small, so crushed by the immense force of the water that reaches us, enters us, wrecks and resurrects everything in us. But we stay there. Captivated.” Their idyll is interrupted by a French military helicopter. An armed soldier menaces them from above. Malika is stunned: “A flying machine and a soldier dangling his feet in the air. He’s not at all afraid. Me, I’m terrified. I see the soldier as something not human, not of this world, of our world. Something that heralds the end of the world.”

A storyteller and caster of spells, Malika speaks in phrases that, like the sublime waterfall, cascade down the page. Ramadan’s fluid translation captures the tumbling quality of her voice and emphasizes how her meaning is carried along by rhythm and accretion. In one scene, Malika speaks to her daughter, Khadija, who is tempted by an Arabic-speaking Frenchwoman, Monique, to join her household as a domestic servant. As Malika makes her argument against this plan, her points glide through her sentences in a way that shows how sentences can function not just as containers for discrete units of meaning but connectedly, forming a conduit for a powerful flow of ideas:

They mock us, Khadija, us together with our beliefs, our mausoleums, our saints. For them, it’s folklore. Our very lives are folklore. I’ve seen and heard them laughing at us in the halls of the National Library. They see us as savages. You, Khadija, are so beautiful and pure, they see you that way too. You are nothing to them. Nothing. But I, I won’t let them take away your beauty. Lock up your beauty. Use your beauty as decoration, an embellishment. You won’t be Monique’s slave. You hear me?

Another note about the translation: Ramadan leaves Arabic words untranslated, implicitly reminding the reader of the complexity of Malika’s linguistic context, in which Moroccan Arabic jostles with French. But since this vocabulary is not always familiar, Ramadan includes simple notes to clarify the meaning; otherwise her presence is unintrusive, allowing Malika to shine forth unimpeded. Altogether Living In Your Light is an absorbing story told in melancholy retrospect by a compelling woman caught repeatedly in the riptide of colonial power and still somehow swimming indomitably toward the shore of a life lived on her terms.

+++

Born in Rabat, Morocco in 1973, Abdellah Taïa has written many novels in French, including Salvation Army (2006), Le jour du roi (Prix de Flore, 2010), Infidels, translated into English by Alison Strayer (Seven Stories Press, 2016), and A Country for Dying, which was awarded the PEN Translation Prize for Emma Ramadan’s translation (Seven Stories Press, 2020). His most recent novel Le bastion des larmes was shortlisted for the Prix Goncourt 2024 and won the Prix Decembre 2024. He is the director of two award-winning feature films, Salvation Army (2013) and Cabo Negro (2025). He lives in Paris.

+

Emma Ramadan is an educator and literary translator from French. She was awarded the PEN Translation Prize for Abdellah Taïa’s A Country for Dying, and has also received the Albertine Prize, two NEA Fellowships, and a Fulbright. Her other translations include Anne Garréta’s Sphinx, Kamel Daoud’s Zabor, or the Psalms, Kaoutar Harchi’s As We Exist, Marguerite Duras’s The Easy Life, and Barbara Molinard’s Panics.

+

Diane Josefowicz is books editor at Necessary Fiction. Her next book, Guardians & Saints: Stories will be published later this year by Cornerstone Press.