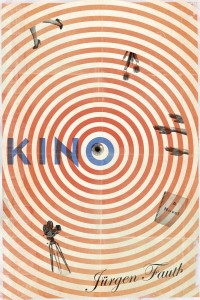

Atticus Books, 2012

“Art is free. However, it must conform to certain norms.” – Joseph Goebbels, Hotel Kaiserhof Berlin, 1927

Rather an ominous quotation with which to begin a novel, yet invoking Nazi Germany’s Minister of Propaganda and his horrifying vision of artistic freedom sets up a perfect frame for Jürgen Fauth’s début novel, Kino.

Kino is a messy, wonderful, loopy romp of a novel. Written in an easy style conducive to breakneck reading and filled with cinematographic trivia, falsified histories, real histories, political criticism, romance, car chases, airport bomb threats, copious amounts of narcotic substances and a 92-year-old foul-mouthed ex-starlet. And that covers just about the half of it.

At the center of this uncommon novel is Wilhelmina “Mina” Koblitz, an ordinary young American woman, recently married to game designer Sam and just home from a failed honeymoon (which happened to follow an equally disastrous wedding reception). Sam is stuck in the hospital with dengue fever when Mina receives a mysterious reel of film at their NYC apartment. The arrival of this film sends Mina to Berlin for only the beginning of her riotous and life-altering adventures.

The film is Tulpendiebe, or, The Tulip Thief, a 1920s silent film made by Mina’s long-forgotten grandfather, Klaus Koblitz, otherwise known as Kino, which is also the German word for film—a self-selected moniker that reveals Mina’s grandfather’s sense of his own talent. For years, Kino’s films were believed to have been lost, destroyed by the Nazi’s before Kino and his wife— a would-be physicist turned actress who made history for them both in Tulpendiebe —immigrated to America. But nothing is straightforward, as Mina soon learns, about Kino’s history and especially about the meaning and import of his films.

Kino takes Mina from Berlin to LA as she hunts for the truth of her grandfather’s legacy. There are conflicting accounts to sort through, much family resentment to negotiate and several revisions of “the facts” to decipher. On just this one level, the novel is interested in how family histories are created and the difficulties in finding an acceptable “truth” in circumstances long past. Memory is a fallible resource.

Within this more domestic story, however, Fauth asks questions about the power of art to influence reality. The discovery of Kino’s long lost films is of interest not only for their artistic value, but also because they appear to contain a kind of inexplicable and subtle prophesy. Tiny scenes that are translated into reality at some later date for the film’s various viewers.

In his recovered journal, written while in psychiatric care near the end of his life, Kino tells a version of his life story, “his” version, of course. In that short document, which Mina is mysteriously given while in Berlin, he paints the picture of a man empowered by a late discovery of cinema. He is 22 years old and has never seen a film. This is his reaction when an influential friend takes him to the movies:

You’ll never understand the rapture, the horror, the euphoric bliss I felt at the sheer visual surprise. With each passing moment, with every new shot on the screen, waves of pleasure rolled through me. […]

… I loved the ghastly shadows of overgrown nails, the meat-eating plants, the sleepwalking bride, the caskets filled with plague-bearing rats. This was the opposite of father’s newsreels, this was the technology of the night, modernity pressed in the service of poetry, culling images from dreams and rending them visible as if by the light of the moon, for all to see.

It was magic.

So it should come as no real surprise that Kino’s films manage to embody some version of this magic, that certain tiny visions he frames and shoots and edits somehow become reality. Fauth has one character call these incidents “echoes” and this tangential storyline propels much of the action-filled movement of the novel. There are people interested in the secret powers of Kino’s films—for commercial and other more dangerous reasons—and Mina ends up racing around California to save herself and her grandfather’s legacy.

This element of the novel also gives Fauth the opportunity to create a series of parallels, subtly attempted but admittedly somewhat awkward in accomplishment, between Nazi ideologies and American politics under the second Bush presidency. The problem with these comparisons is less a problem of scale and more that Fauth’s Mina (and Sam, for that matter) isn’t as realized as she could be. Some of the novel only works because Mina doesn’t know a thing about German film or the tensions between art and politics at this particular time in history. This is perfect because Fauth can use her ignorance to inform the reader without giving lectures, but the flip side of this is that Mina tends to come across as rather blank. And so when she suddenly voices an opinion, like calling Paul Bremer a “lying sack of shit,” it can seem more like a knee-jerk reaction of her demographic instead of an informed political judgment.

Much of the joy in reading this kind of novel comes from an admiration of the author’s research and skill in putting that research together into a coherent story. Kino is filled with real historical characters and events—people like German filmmaker Fritz Lang, actor Rudolf Klein-Rogge and many others, and of course Goebbels and several events pertaining to the Third Reich’s negotiation of German art and culture during the 1930s and 40s—but the novel cleverly inserts itself as a fictional footnote to this period of film history, even going so far as to suggest that the discovery of Klaus “Kino” Koblitz’s films will necessitate a re-evaluation of the merit of certain film makers previously credited with the development of revolutionary techniques. Suddenly, deliriously, the “real” and the “possible” begin to merge. Fauth becomes Kino—or is it the other way around?

Kino is also, perhaps most of all, a splendid homage to German film history, especially the 1920s tension between expressionism and more realistic film techniques. That tension is played out structurally in the novel as it shifts between an over-the-top crime story of secret agents (or are they?) out to hunt down a 1920s silent film at all costs and the more domestic issues of family memory and marital discord. Uniting these two elements was certainly no easy task and is at times unwieldy, and yet the book ultimately makes an elegant argument for this very roughness:

My utopias had nothing to do with perfection because perfection is not something to strive for. All my movies were flawed, and I wouldn’t have it any other way. Mapmakers always insert one wrong detail into their maps—a lake that doesn’t exist, a county line that stretches a hilltop too far, a misspelled street name. It is a way to identify unauthorized copies, but it’s also an opening through which the infinite rushes in: if one thing is wrong, then anything might be wrong. It’s the same principle through which a single blank bullet calms the conscience of the entire firing squad.

+++

+