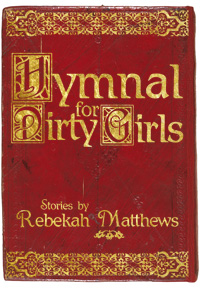

Big Rodent Books, 2012

Near the end of the first story in Rebekah Matthews’s short story collection, Hymnal for Dirty Girls, the first person narrator, who is sitting in a car on a fairly bizarre stake-out with a woman she is clearly in love with, has the following thought:

…I wonder what your husband is like. I wonder what he thinks about you spending so much time with me. I wonder if it’s nice to bring him along to family reunions, work parties, and there is nobody you’ll alarm or disturb or make curious. You don’t have to explain anything.

That last thought, offered up so quietly by this unhappy narrator could have been worked into each of the six stories of the collection and would have accurately described the narrator’s underlying concern — how nice it would be to never have to explain oneself, to never disturb or upset anyone. Matthews’s narrators are distinct enough from each other to make each story its own, but they do all share a particular emotional pitch, a kind of painful bewilderment with respect to the difficult situations in which they find themselves. These six women are all a bit wounded, and as a result, also a bit paralyzed.

The narrator from “About a Year Ago,” the mid-point and most complex piece in the collection, is perhaps the greatest example of that paralysis. Here is a woman in a situation she clearly finds unsettling. Matthews gives only tangential specifics to acquaint the reader with this narrator’s unhappiness — the ant infestation in the woman’s apartment, her distrust of a crowd of close-knit sorority-style women at work — although her unhappiness seems to be coming from a place much further in the past than the story’s present concerns. The focus of the story is actually the narrator’s relationship with a much older woman named Julie, a relationship which, on the surface, appears to be going well. Only Julie has a tragedy in her recent past and once she reveals this, the narrator freezes. Panics. There is an obvious fear of having to take on Julie’s recent grief, but there’s more than that. It is as if Julie’s revelation takes away the narrator’s right to be unhappy herself, and it’s this worry that makes her walk away. The story is short, but wonderfully subtle.

That subtlety also comes from the way in which Matthews handles the natural story arc. Each of these stories is in some way truncated. Not unfinished, but Matthews resists the rounded out conclusion, and she reins in each piece a few lines in, or even a scene in, from where another writer might push the feeling further, might reach for the neater tie-up.

The title of the collection is a curious one. Certainly provocative. I immediately expected a story of the same name but there is none. Hymnal for Dirty Girls suggests a thematic preoccupation with sex, especially sex that might carry judgment from some. Although Matthews does not shy away from sex as an element of the collection, it is not the collection’s overt focus. And nor could any of the characters be considered “dirty girls.” These are polite and kind young women — lost perhaps, unmoored, but never vulgar or offensive. Most are lesbians, and so the juxtaposition of the word hymnal with that confrontational label dirty girl becomes, through the stories, a fantastic subversion of the very idea that these women are in any way “dirty.” Here is a book of love songs, really, ballads for those who may be asked too often and too unfairly to “explain themselves.”

+++

Rebekah Matthews is from Indiana and lives in Boston. Her work has appeared in publications such as Storyglossia, SmokeLong Quarterly, decomP MagazinE, and Necessary Fiction. She is currently at work on a novel.

+

Michelle Bailat-Jones is a writer and translator living in Switzerland. Her fiction, translations and reviews have appeared in various journals, including Ascent, The Kenyon Review, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Atticus Review, Necessary Fiction, The Quarterly Conversation, Cerise Press and Fogged Clarity. She is the Reviews Editor here at Necessary Fiction.