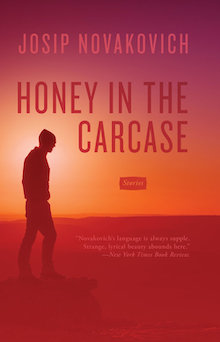

Dzanc Books, 2019

Like a master painter, Josip Novakovich sets his skillful new collection, Honey in the Carcase, against a shifting background of conflict — home and the family, war and displacement, love and betrayal. The stories are at times morose and bitter, and at other times, playful and joyful, experimenting with voice and perspective as much as with topic. Novakovich seems to move about in time, but some of the stories feel more distant from others than they probably are.

While reading the second story, “Tumbleweed,” in which a Yugoslav graduate student hitchhikes through the midwest, gets stranded, and gets arrested — I wrote in the margins, “nothing is as it seems, or should be.” The driver who picks him up in a pickup truck is bringing a snowmobile to his father in Missouri, even though it’s the summer. “So what?” he says, “Soon it’ll be winter.” When the Yugoslavian, constantly confused for Iranian, Czechoslavakian, or Russian, gets stranded, he is arrested for hitchhiking and being drunk in public, and is accosted for his driver’s license, despite the fact that he isn’t driving. “I’ve got a green card,” he offers. When he finally boards a bus to leave town, the man who sits beside him tells him about the beautiful courthouse, where he had just been fined, “but of course, you wouldn’t have seen that.” Driving away, they pass a smashed pick up truck, totaled by a mobile home. “An intact gray snowmobile stood beside them, like a faithful dog waiting for its drunk master to get up from the ditch.”

This sort of bewildering aptness continues throughout the stories. Novakovich has an incredible gift for ending a story, alternately wrapping together loose threads, as in “Tumbleweed,” or propelling the reader out to wonder in silence for a moment, before being transported to an utterly different and new place, as he begins the next story.

Animals thrum with the same energy as human characters—in some cases, quite literally. Bees figure prominently in the titular story, “Honey in the Carcase,” an entity to be cared for, but also one that provides for and protects their human. In “Wool,” a young girl, Anna, devotes herself to a pet goat, Tanya, who is later butchered by the girl’s horrible father. Tanya is both a playmate and a terror, wrecking the family garden and eating grapes from their vineyard, and butting heads with neighborhood children in a natural burst of competition that Anna can’t nurture out of her. As the stories progress, the animals take on more agency of their own. In “Fritz: A Fable,” a Croatian couple are initially aggravated by the conflict between their dog and a stray cat. As their town is attacked by Serb armies, the wife flees for Hunagry, writing home that she felt unsafe. “How were animals to understand war?” Novakovich writes, and when the man returns to the house, which he has been forced to abandon, “the dog’s paw gently and protectively lay over the tabby’s shoulders,” — they have formed a familial bond across species and taken the house for their own. A boy longs for companionship from the hawk he is raising in “Yahbo the Hawk,” and confronts the fact that just as he cannot domesticate a wild creature, he cannot comfortably kill in order to provide prey for Yahbo, whom he ultimately sets free, to a mournful result.

The contrast of the familiar and the foreign throughout the collection feels at times gentle, and at others, aggressive. Some of the stories are quite strange—the pair, “Lies,” and “Counter-Lies” follow two brothers, from a myth of the older brother’s (physically) tiny army to the younger brother’s discovery of the unbelievable, tap water, electric cable cars, a train threading through a mountain via a tunnel. Novakovich plays with lying and gullibility throughout the two pieces, one brother seeming to be powerful, because he is older, his lies lighthearted to the reader and mythical to his younger brother, who, when he later has an opportunity to lie, does so to build a reputation of knowledge, authority, and wonder. Another odd story is “My Hairs Stood Up,” the only story to be told through an animal’s words, is from the perspective of a rodent who initially admires humanity, but after a harrowing series of events, finds himself full of hatred. “My Hairs Stood Up” manages to both fit in and stand out from the rest of the collection for the same reason: its successful capturing of the feelings of alienation and despair, violence lingering in the background.

There is a harmony in the cohesiveness between some stories and then sudden disorientation as voice, place, or mood shift without warning. “Charity Deductions,” the most glaringly satirical story, ought to feel out of place, but doesn’t. The collection as a whole manages to feel almost like a portfolio, pulling from thin air an incredible range of techniques and intentions, but producing them all in a remarkably clear and consistent style. Novakovich’s prose is spare, but not austere, and he lets dialogue, thoughts, and actions take up the right amount of space, letting each moment speak for itself without being mired in unnecessary complexity.

+++

+