Two-way propositions: in the first

example, the prepositional phrase

describes a destination. In the

second, it describes a location.

German indicates this distinction

through the use of cases

(Wohin/where to? Wo/ Where at?)

3:AM Press, 2013

These are the opening lines of Joanna Walsh’s chapbook, Hauptbahnhof, published this summer by 3:AM Press. It is a woman’s soliloquy, seemingly addressed to a man who never shows up at the train station to meet her. She continues to wait for him in the giant Hauptbahnhof (Central Station) in Berlin.

I pride myself on travelling light.

Waiting, it is necessary to look as

if you are expecting an arrival,

She writes to her “beloved,” without rancor, while communicating the strategies involved in “waiting” interminably for him to arrive. She must simultaneously hide her homelessness and keep up the appearance of simply waiting for his arrival.

I know what you are thinking.

But it is possible to sleep on the

station.

If you don’t look like a tramp, if

you change your clothes with

reasonable regularity, above all if

you look like you are waiting for

someone.

I have perfected the waiting look.

This chapbook, which plants us firmly in the absurdity of the narrator’s desperate and untenable decision, creates the feeling of a dream, stretching the romantic notion of “longing” into an extreme which contains its own logic.

The Hauptbahnhof is open 24/7.

Coincidences arrive at any time of

day or night. I have become used to

the sound of trains.

She is waiting for that coincidence, the waiting for something to happen, something other than what is happening now.

After all, even if I am no longer

sure whether I am waiting, or

whether I only wish to appear to be

waiting, it is my responsibility to

not cause a ‘situation’, an

incident. It is my responsibility to

protect the people who pass through

the station from the sight of a

woman alone who is not waiting for

anyone. Although, of course, I am.Obviously, a lot of time has passed:

Of course I did not then speak

German.But I have improved (you would be proud).

I thought of Djuna Barnes’s writing, “What is a ruin but time easing itself of endurance?” Everything is available in this world of technological excess. But none of it brings people together.

That first night I called you a

couple of times but you didn’t

answer. It’s possible I got your

number wrong. I emailed you

regarding this but you did not

reply. I thought perhaps you were

playing games, that you would relent

or that, when we met, you would

provide some good reason. Maybe it

was a joke. I thought your phone was

out of charge, that you had no

connection. I thought you had lost

it, that it had been stolen. I

thought you were busy, were

unavoidably detained, would answer

later. I thought you had been

arrested or were in hospital. I

thought you were dead. There were so

many possible explanations: I saw no

reason not to hope.

If this chapbook is meant as a letter, we have no idea how it will reach the person it is meant for. She is, after all, waiting for someone she barely knows.

It is only sometimes that I think

you are, perhaps, not still living

in Berlin.I heard you were in Edinburgh,

“Pleasure disappoints, possibility never,” wrote Soren Kierkegaard in The Diary of the Seducer.

The tone of the story feels congruent with the physical reality of the paper it is printed on, in Courier type, on substantial paper stock, a cardboard cover, bound with staples and tape. I love that there are no blurbs or price tags to mar the intimacy of the writing. I can imagine finding it left on a bench at the station.

Surely everyone who lives in Berlin

must pass through the Hauptbahnhof.

It is only a matter of time.

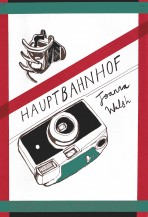

_ Hauptbahnhof_ is illustrated by Christiana Spens, and her bold yet minimalist cover illustration of a camera and a hair clip is a reminder of what is entailed in this tourism of “waiting.”

The physicality of the chapbook is contrasted with the non-physicality of the longing to connect with an “other” who appears to be nothing more nor less than a reason to “wait.”

I am reminded of Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot,” as our predominant mode of being is one of waiting or “becoming.” Or, due to the elaborate steps she’s taken to live and, not only survive but, thrive in the Hauptbahnhof, it might be more as Derrida has suggested, “We wait for something that we would not like to wait for.”

Do I miss home? How would I? On the

highest Level there is a shop with

things for houses.

Lifelike plastic dummies sit in

deckchairs in the window. Everything

is new, perfect.

Walsh deftly infuses a heartbreaking situation with a strange sense of optimism. _ Hauptbahnhof_ is simultaneously sad and funny and human, reminding us that we, too, might be waiting for life to happen.

+++

+

.