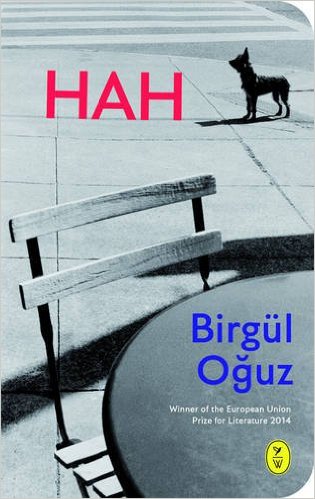

World Editions, 2016

HAH, by the Turkish writer Birgül Oğuz, is described as a short story collection that reads like a novel. But coming in at just over ninety pages, this novella of linked prose narratives defies conventional forms. The book won the 2014 European Union Prize for Literature and the translation from Turkish to English is a joint effort between nine translators. The collective effort of the translation is in itself unique; the front-page copy reveals that the translation began in 2014, in collaboration with the author, at a workshop for literary translators in Turkey.

The reader begins HAH with incomprehension, but the style and imagery is strong, idiosyncratic and gripping, keeping the reader interested until a picture starts to emerge. The novel is structured into three sections: “Salt,” “Into,” and “Water.” Each section holds several narratives. At the start of the book, the picture is vague, a little blurred around the edges, but it gradually becomes clear: a woman has lost her father and the process of grief has completely taken over her waking existence:

She turns her back on the fresh grave. She brings this house of mourning down upon us. Hiding under the covers, she hisses at our souls. She leaves the body behind, like a dark house, and is gone.

This first narrative, titled “Return,” opens with arresting imagery of the speaker becoming an acacia tree: “Sentience is anguish to the soul and I never tasted of it. I am solitude. I am that which is distant to the world.” The effect here is the rendering of a particular totalization—a person’s life and thoughts colonized by grief.

The narratives that follow, “Stop” and “Speak,” borrow images from the Bible, depicting the grieving daughter as the sacrifice nailed to the cross, the (lost) father as an unreachable god. Death is the ultimate distance that cannot be crossed. As Oğuz writes:

Fathers, however, shouldn’t be loved; they’re too fragile for that. Once they are loved, they quickly get shorter and die. People call this mourning first, and then law. It happens like this. The child takes the gun. On the tip of the barrel: an indecipherable father.

The Freudian principle of the usurping son is thus complicated when the family unit has instead an adoring daughter, one made in her father’s image: “You see, I needed a father whom I would defeat. I would make him fall out of my favour when I was weaned. I would no longer sing his praises when there was hair on my pudenda.” This combination of pathos and black humor underpins much of HAH, giving shape to an irrepressible and wholly original voice.

“I am the failed apprentice of an already wounded father,” the narrator writes. The middle section contains just one narrative, titled “Revol,” a nod to the revolutionary aspirations of the father, a member of the Turkish 1968 generation. The surreal styling of this section, where the young narrator attends a protest with her father, is filled with nonsense rhymes, alliteration, and energy, as well as the spark that fuels the narrator’s own nascent desire for revolution: “Even back then I knew that such a gathering of people was akin to victory. Tongues of flame, the churning of water, the howling whirl of wind, that what we were and that’s what we said, enough already!” The ensuing military coup in 1980 and the suppression of communists are an ever-present source of anguish for the narrator, and it rubs up against the radical politics she inherited from her father. Clues dropped throughout the text refer to Lenin, Trotsky, and the narrator’s learned resistance to capitalist society. The father appears as a phantom of revolutionary regret; the narrator explains that the father departed saying, “There is yet another revolution.” The reader is made to understand that the collective grief of a generation, what the father lived through in Turkey, is the unsolved mystery at the heart of the national malaise. Father and country are not one, and in fact were at odds, but the death of the father reveals what’s rotten in the heart of the state.

In writing and crafting HAH, Oğuz has created a landscape of grief and mourning that incorporates sights, sounds, and images of everyday life as well as dreams, nightmares, and fantasies that serve to both maintain a distance from reality and draw it closer. It is, in essence, an attempt to dive deep into the human experience of pain and the mechanisms and processes of coming to terms (or not) with loss. The text is rich with symbols and allusions, many of which might be lost to the reader, especially to the non-Turkish reader of the English translation. While this element of impenetrability in some layers of the text heightens its mystery, the deep wisdom and dark humor embedded in the text still resonate strongly. Despite its stark exploration of pain and political exhaustion, HAH is also about the enigmas of human experience, and it weaves an enchanting spell with its philosophical ruminations and bold aesthetics.

+++

Birgül Oğuz was born in İstanbul in 1981. In addition to HAH, she is the author of Fasulyenin Bildiği (2007). Her short stories, essays, articles, and translations have been published in Turkish literary magazines and newspapers. In the winter of 2013, she was invited to be a writer-in-residence by quartier21 in MuseumsQuartier, Vienna. Currently, she is studying a PhD in English Literature at Boğaziçi University, and she lectures on text analysis and the European novel at Moda Sahnesi and Nazım Hikmet Academy in Istanbul.

+

Subashini Navaratnam lives in Selangor, Malaysia. Her writings on books have appeared in The Star (Malaysia), Pop Matters, 3:AM Magazine, and Full Stop. She has also published fiction and poetry. She tweets at @SubaBat.