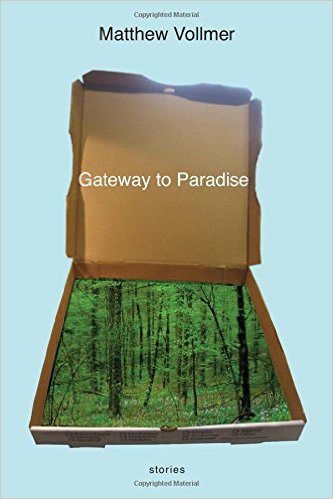

Persea Books, 2015

Many of us daydream about escaping the day to day monotony. When set in a routine, there is comfort in dreams of running off and leaving it all behind, or curiosity about who we would be with other people and how we would look through their eyes. In Matthew Vollmer’s latest collection, Gateway to Paradise, his characters find themselves standing on the precipice of moments that could be life changing, possible paths to alternate realities in which they could be happier. But as with all decisions made in the real, non-fantasy world, consequences lurk just around the corner.

Most of the short volume is comprised of stories deeply rooted in reality, set in the South, populated by characters who feel relatable, if not quite likeable. They are flawed, with human inclinations that many readers have probably given a few moments to on a dreary, downer day. But the characters in these stories have opportunities to act on impulses that could completely change their lives, possibly bringing more happiness or fulfillment. In the titular story, a young woman and her boyfriend hatch a deadly plot to leave their small hometown. In “The Visiting Writer,” an adjunct professor is drawn to the mystery of an older, accomplished writer he’s volunteered to chaperone during a campus visit. In “Probation,” a father’s concern for his daughter forces him to decide if the risk of violating the terms of his house arrest is worth tracking her down.

Others don’t quite land right. The opening story, “Downtime,” finds a grieving widower confronted by his wife’s ghost, a premise that starts strong but ends weakly as the lines between the living and the dead become too blurred. Another, later story, “Dog Lover,” takes the “will-she, won’t-she” question too far when a woman explores intimacy with her beloved dog. These stories feel out of place, pushing boundaries in ways that don’t make them any more engaging or illuminating than the others.

What Vollmer does well in all stories, however, is peel back the layers of his characters’ lives. The reader is parachuted into each story, abruptly entering the private lives of other people. There’s a voyeuristic element to Vollmer’s writing, but one born of his ability to fully inhabit the minds of his main characters. In the space of a few pages, the reader is plunged into their stream of consciousness, peeking in on their insecurities and rationalizations: “Before today, it had been sixteen days since Abe called Gina, a fact he hopes she’s noticed, since it supports the theory that he’s cool with their trial separation thing, even if Gina’s never used the world trial to qualify the word separation.”

Most stories have a slow burn to them, setting up the workaday lives of the characters before the tension fully sets in. One exception is “Gateway to Paradise,” which conveys a sense of danger and urgency almost immediately. The stakes become clear, and the internal push and pull between desires and responsibilities comes sharply into focus. A man struggles with the constraints of a tight budget and rote marriage when he meets a young, seemingly interested woman at a shopping mall. A dire and dangerous situation makes a woman question her future with a volatile man. Risks and rewards are weighed in equal measure.

Almost every story contains a free-flowing interlude that reads like a ball rolling down a hill. By the time it stops rolling, you’re in the character’s head. From “The Visiting Writer”:

The visiting writer asked me to wait a moment. I wasn’t sure I had a choice. Watching her dig through her suitcase, I felt myself teetering on the brink of some preordained transgression, one composed by whatever Author was writing the script of my life, in which I was doomed, whether I wanted to or not, to make a tragic mistake. I had imagined, and thus it could be said, wished for an escape from normalcy, from the safety of my family—for whom, in a heartbeat, I would have given my life—and from the drudgery of my job, which was the exact job I’d always wanted, and which thousands of other people, many of them more qualified than I, were striving unceasingly to obtain. As idiotically self-destructive as it was, I couldn’t help wonder what it might be like to open up a hole in my life, to slip into a darker realm where I would be utterly—and no doubt deleteriously—transformed.

Just as abruptly as the stories start, they end. Vollmer doesn’t linger after the decisions are made. The consequences that will presumably play out weigh heavily after the final lines. The reader can’t help but wonder what comes next, what fallout follows the overspending or professional misstep or solitary walk into the woods. Whether everything or nothing changes is left a mystery, one that will keep the reader thinking long after the collection is finished.

+++

Matthew Vollmer (www.matthewvollmer.com) is also the author of inscriptions for headstones, essays. His work has appeared in Tin House, Glimmer Train, The Paris Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, Best American Essays, The Pushcart Prize anthology, and elsewhere. He directs the undergraduate creative writing program at Virginia Tech.

+

Bridey Heing is a freelance writer based in Washington, D.C. She has written reviews for The Daily Beast, The Mantle, Paste, The Intentional, PANK, and Bust. Her writing has also appeared at The Guardian, Guernica Daily, Hyperallergic, and Broadly. You can also find her on Medium and at www.brideyheing.com