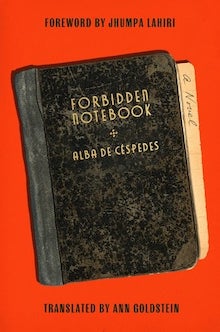

Astra House, 2023

Published in 1952 after being serialized in a weekly magazine, Alba de Céspedes’s Quaderno Proibito made waves at midcentury for putting a lens to female subjectivity. Ann Goldstein’s new English translation has reinvigorated the novel for contemporary readers and restored de Céspedes, once one of Italy’s most successful authors, to the spotlight. And rightly so: Forbidden Notebook explores the depths of a woman’s domestic discontent and the powerful consequences of writing oneself into agency, two themes that still have enormous relevance today.

“It’s strange: our inner life is what counts most for each of us and yet we have to pretend to live it as if we paid no attention to it,” says Valeria, the protagonist, a pressured wife and mother in post-war Italy. The notebook offers her a chance to attend to her inner life. But Valeria hides the notebook, aware that a diary offers both privacy and exposure. Writing in the notebook becomes an act of transgression and resistance, echoing the rebellious facts of de Céspedes’s own life; she was twice imprisoned for anti-fascist activities, and two of her books were banned.

In Valeria’s first entry, she writes, “in the entire house, I no longer had a drawer, or any storage space, that was still mine.” Even her daughter, Mirella, who’s studying law, has a locked drawer. When Valeria says that she, too, deserves a drawer of her own, her family members ask, almost in unison, what for? Maybe in which to place a diary, she says hypothetically. “I dream of having a room all for myself,” Valeria writes. “Even a maid who works all day without stopping says, ‘Good night’ and has the right to shut herself in a room, in a pantry. I’d be content with a pantry.”

“In lieu of walls and a door,” Jhumpa Lahiri writes in the book’s preface, “pen and paper will suffice to allow Valeria, albeit furtively, to speak her mind.” Although the notebook fails to provide a physical space, it nonetheless serves as a vehicle for self expression. Through the notebook, we get to know Valeria as both a woman and writer. De Céspedes would have been aware of Virginia Woolf’s essay “A Room of One’s Own” (1929), in which Woolf suggests that financial freedom for women was more important, even, than the right to vote, and that a woman’s right to write is more important still.

Writing functions as the antithesis to Valeria’s familial and financial obligations. While Valeria’s husband reads the newspaper in his armchair or listens to music after work, Valeria returns from her office job and heads straight for the kitchen. Her family tells her to rest, but the moment she does, someone says, “Mamma, since you have nothing to do, could you mend the lining of my jacket? Could you iron my pants?” But rest, for Valeria, entails other losses: “if I admitted I’d enjoyed even a short rest, or some diversion like window shopping or a nap, I would lose the reputation I have of dedicating every second of my time to the family.”

Valeria’s diary-keeping permits her to examine herself through the words she writes, yet instead of experiencing release from the many roles she must play, she is deflated by what her life has become and stunned to learn of her own needs and desires. “I know that my reactions to the facts I write down in detail lead me to know myself more intimately every day,” Valeria writes. “Maybe there are people who, knowing themselves, are able to improve; but the better I know myself the more lost I become.”

As Valeria faces herself in her pages, she fears that dissecting her feelings turns them into poison; she fears becoming the criminal the more she tries to be the judge. In de Céspedes’s work, women tend to judge the rightness or wrongness of their actions. In Forbidden Notebook the act of writing – itself clandestine – blurs the line between truth and fiction; Valeria must lie to tell the truth. Caught in this vicious cycle, Valeria repeatedly threatens to destroy the notebook, imagining the smell of burnt paper lingering in the air. “All women hide a black notebook, a forbidden diary, and they all have to destroy it. Now I wonder where I’ve been more sincere, in these pages or in the actions I’ve performed.”

Reading her own words back to herself, Valeria realizes that she lacks the courage to liberate herself. Of her daughter, Mirella, Valeria wonders “if there is not more compassion in the coldness with which she protects her life than in the weakness with which I agree to let mine be devoured.” She struggles to entertain ideas of an alternate life with Guido, her boss, who wants to go away with her: “We would be in a prison there, too…behind bars that we can’t break down because they’re not outside us but in ourselves.” She knows they have the right to be in love, but “to use a right, one has to not feel guilty using it.” The conflict of guilt and shame crossed with joy and fulfillment plagues Valeria. She knows exactly what she wants but chooses to edit her own desires. She cancels her own words, and in doing so, cancels herself.

+++

Alba de Céspedes (1911–1997) was a bestselling Italian-Cuban feminist writer greatly influenced by the cultural developments that led to and resulted from World War II. In 1935, she was jailed for her anti-fascist activities in Italy. Two of her novels were also banned—Nessuno Torna Indietro (1938) and La Fuga (1940). In 1943, she was again imprisoned for her assistance with Radio Partigiana in Bari, where she was a Resistance radio personality known as Clorinda. After the war, she moved to Paris, where she lived until her death in 1997.

+

Ann Goldstein is a former editor at The New Yorker. She has translated works by, among others, Elena Ferrante, Pier Paolo Pasolini, and Alessandro Baricco, and is the editor of the Complete Works of Primo Levi in English. She has been the recipient of a Guggenheim fellowship and awards from the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

+

Katy Dycus holds a Master of Letters from University of Glasgow and works as a staff writer for the anthropology journal Mammoth Trumpet. Her work has appeared in Huffington Post, Lady Science, The Wild Detectives, Hektoen International, and Tupelo Quarterly.