Salt Publishing, 2012

Entertaining Strangers opens with a brief Prelude describing a fire which happened seventy-five years before. Both the Prelude, and the novel itself which is set in 1997, are narrated by Jules, who in 1997 seems to be a relatively young woman. So far, so confusing…

In the first chapter, Jules sits down for a minute, “on a dog-piss-soaked doorstep in a dog-piss street in a dog-piss town,” when the door behind her opens, depositing her, and us, into a setting only matched in squalidness by the set of The Young Ones. Edwin appears, wearing a pom-pom-trimmed dressing-gown belonging to his landlady, talking about ants, and offering vermouth. We begin to suspect that we are in for a strange ride indeed.

Edwin, we quickly ascertain, is one of life’s more eccentric individuals, and has managed to surround himself with similarly unusual people, not least the (apparently) time-travelling Jules. Then there is his landlady, with whom he sleeps in lieu of paying rent, the poet he encounters in his local, his neurotic mother, and his psychotic brother.

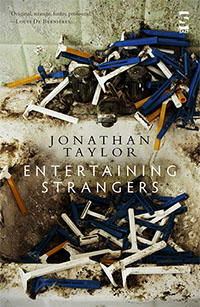

Even the cover, strewn with used razor blades and patterned with ants, plays its part in inviting us in to the weird and wonderful story Taylor weaves around these characters and their unconventional lives, in lively and highly entertaining prose. It is easy to care about these characters, what their relationships are, and what will become of them. We even care about the ants in Edwin’s ant-farm, because, as becomes quickly evident, we are in the hands of a writer fully in control of his craft.

There are many moments of genuine emotion, such as when Edwin receives a letter from “the mother,” which he promptly screws up and throws into the ant-farm after reading. But later that night, when Jules can’t sleep, she sees Edwin leave his room and go out into the yard. She sees him return to his room, only to go out again soon after. Eventually she investigates.

… looking down at the and-farm, I noticed that the lid of the foraging tank was a bit askew. I was readjusting it, when I saw the screwed-up letter from Edwin’s mother. I thought it looked different: it seemed to be in a different place in the tank, and was now more folded than screwed.

These moments combine with a deliciously anarchic humour. With Edwin’s wife’s “Dear John” letter to Edwin, and its many post-scripts, Taylor makes the best use of the epistolatory device since Jane Austen. The reader cringes a little at its opening:

Dear Edwin, By the time you read this letter, I will be gone.

As we have grown accustomed to his accomplished technique, with this line we feel as if his interest in meeting our by-now high expectations has waned. That is, until we get to the P.S. and realise with an “Ah ha!” that he was just teasing:

The reason I began the letter with “By the time you read this letter, I will be gone” is because I thought it would piss you off if I ended us with a cliché.

The P.S. continues:

God, you think you’re so unconventional, so original, but I’ve seen loads of you on films and TV, usually played by Richard E. Grant or Marvin the Paranoid Android.

Here, Taylor might be addressing his readers, or himself (since we all know how paranoid writers can be!), or even poets and intellectuals in general. In any case, we are reassured that we remain in capable hands.

It is this humour that makes the book unputdownable. Taylor performs a hair-raising balancing act, managing to keep his characters (barely) on the brink of total anarchy without actually going over the edge — even when they do appear to go over the top. Sometimes, like the letter above, the humour is laugh out loud, other times it’s poignant: Edwin’s job in Encyclodial, a premium-rate phone-line where callers can ask for information on any subject and have it read out to them from their library of encyclopedias, is almost plausible — until we remember that this is 1997, and the internet is right around the corner. As the novel closes, Edwin is engaged in the task of writing A Cultural Encyclopedia of Ants, which he expects will be 3,000 pages long; he’s “getting through the As as we speak.”

Taylor’s language is accomplished and often beautiful. A passage describing the “dog-piss town” in which the novel is set is arresting in its rhythmic, grimy beauty:

— through some dark, Satanic streets, down a flooded alleyway, past a half-lit business of an unspecified nature called Club Class, along the towpath of a disused canal, over an abandoned shopping trolley — until we reached The Dying Swan, a pub locked in beery twilight.

There is a welcome freshness in the recycling of well-worn phrases: “striding to and fro, fro and to.” Or: “forwards and backwards, backwards and forwards.”

However, when Taylor repeats this phrasal structure, as he repeats the description above (albeit with small changes to mark the progress of the novel), it raises the question of whether a novel can be too well structured, too skillfully crafted. His use of repetition, as well as the overt structure of classical drama (Prologue, Acts 1-5, Entr’acte, Epilogue), draws attention to the novel’s scaffold, which at times become a bit of a sticking point; if the art of fiction lies in dreaming up stories — at which Taylor excels — surely the craft lies in making the stories seem real, in not leaving stuff lying around to remind us that we are reading a book.

Taylor is too good to leave anything around by accident, so one can’t help feeling that he is keeping a foot in the metafictional camp, as if to pre-empt any potential debate. Thus, when we begin to deduce that Jules has come from another time, that we might be in simple New Age territory, Taylor steps in with the landlady’s obsession with guardian angels, filtered through a more than usually cynical narrator, so that Carl Jung is Carlos, and Jung is pronounced with a hard J. Presumably we are meant to dismiss our guardian angel theories. Likewise, when we feel that the denouement is a little disappointing, even puzzling (without spoiling the reveal), Taylor has already pointed out the arbitrariness of the link connecting Jules and Edwin. It’s clever stuff, but with the many ironic side-steps one can’t help feeling as if Taylor does not trust that his story alone is enough to entertain.

On the contrary, Entertaining Strangers drops us as through a portal into another world, or worlds, as vividly imagined as Gulliver’s islands, or Alice’s wonderland, and once we are there we are challenged, and amused, and thoroughly entertained throughout the 300-plus pages.

+++

+