Bison Books, 2011

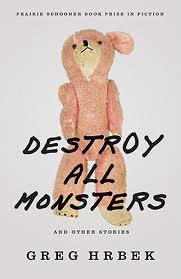

The line between childhood and adulthood is rarely as sharp and defined as we expect. As children we believed being an adult entailed more than having spent a certain number of years on the Earth; there must be something, some intangible magic that turns each child into someone different: the adult version of him or herself. Yet as adults, too many of us find ourselves looking back over the past twenty or thirty or forty years, looking back over a life and wondering how it can be that the magic never happened—we are still, somehow, just children inside. Childhood. Adulthood. Nothing calls into question the difference between the two more than that other critical “hood”: parenthood. Greg Hrbek’s short story collection Destroy All Monsters, which was awarded the Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Fiction last year, addresses just that question. With the exception of the title story, which feels oddly out of place, each story in the book deals in its own way with childhood, parenthood, or, in many cases, both.

While most of these stories remain grounded firmly in reality, the collection begins with a touch of magic realism. In the first story, “Sagittarius,” we meet a young family whose youngest son is born half human, half horse. The baby’s mythical body is the only such magical element in the story, however, and ultimately, the story is about two parents dealing with their opposing feelings about their “deformed” son. Though not technically magic realism, the second story, “Tomorrow People,” also offers a touch of the fantastic by propelling us into the near future (2038), and in the third story, “False Positive,” a pregnant couple is visited by the ghost of the father’s first child, who was aborted.

It is in “False Positive” that the themes of childhood and adulthood fully rise to the surface, though they are certainly present in the stories that come before. Kevin, the aborted ghost’s father, finds himself torn between his desire to be a father, at last, and his indecision over what to do if something serious is wrong with the new baby. He and his wife are preparing to take a second test to confirm a major birth defect in their baby when the ghost arrives on their doorstep, asking to be invited in. Has he grown enough, Kevin wonders, changed enough to have the baby this time around? Will he end up terminating yet another pregnancy? The ghost of his first daughter knows what Kevin won’t find out until tomorrow: the second test will come back positive too.

From there, the stories plant themselves in the realm of the real world, with the possible exception of “Sleeper Wave,” in which a reluctant father’s internet mistress may or may not be a mermaid. Hrbek explores the contrast between being a child and being a parent through multiple perspectives. Though many of the stories give insight into both the child and parent perspective, it is usually the pain and uncertainty, often hesitance, of parenthood that really makes these stories sparkle, as in “General Grant (2004–),” which begins with the unsettling line, “I never wanted a child.” In this story, two parents fight to convince their son, Grant, who has strapped four plastic explosives to his chest, not to go out and blow himself and who knows who or what else up. When Grant goes upstairs to the bathroom before heading out, Grant’s father offers this panicked stream of thoughts:

We’re frozen for a long moment as he disappears upstairs. To “his” bathroom. I listen to the creaking of the steps (the fifth step, the seventh—counting his steps, for some reason), and the creaky steps make me think of the broken keys on an upright piano we once had, years ago, in the old house, in the basement. Grant took lessons for a year or two, then lost interest; then we sold the house and sold the piece of shit instrument for about a hundred dollars, and how hot and hollow my body feels now at the thought of all the pianos people give away and sell for nothing in life, all the piano lessons and hours of practice, every song out of key, nothing ever not out of key, except for once in a great while, once in a while he’d get a whole measure right, in perfect tune, perfect time, and you’d hold your breath and discover yourself almost praying in the uncertain space between notes.

The collection builds toward a crescendo, ending with by far the strongest story in the book, “Bereavement.” “Bereavement” introduces us to Mitch and Carolyn, two grieving parents whose baby boy drowned during a seaside vacation. Mitch, unable to bear the loss of his child, secretly begins working to clone the boy, Rory. Carolyn, however, deals with her sadness by never wanting to have another child again and is tormented by the incessant belief that she has somehow accidentally become pregnant again, though the pregnancy tests she compulsively takes negate her fears. Juxtaposed with the other stories in the book, “Bereavement” seems to shed new light on the whole mess of parenting. Why do we do it, the other stories seem to ask. Because we do, Mitch would tell us. Because what else is there?

[Mitch] was simply amazed (he still is) by the persistence of life’s patterns, how the world breathes in and out without pause, no matter how much death gets visited upon it. . . . He breathes, too—and how surprising it can be to hear his own breath! Like when he wakes up in the night to a darkness so total that even sound and feeling seem to have been disappeared. Then from somewhere inside the darkness, very close by but at a great distance, comes the sound of respiration. A man taking oxygen into his lungs just as he always has. Breathing. As if nothing has happened.

Hrbek’s writing is crisp and often lyrical, and these stories complement each other nicely. Still, some stories in the collection are considerably more engaging than others, leaving the book as a whole feeling somewhat uneven. Regardless, the strengths of the better stories more than make up for the few stories that lag, and though the last lines of even the best stories are often imbued with more weight than the stories seem to have earned, Destroy All Monsters is most definitely worth the read.

+++

+