Your mother throws her breasts over her back when she’s cooking so they won’t bother her. She’s boiling corn, she’s shucking it over the stovetop and she’s half-naked. Her hair’s in a towel. It’s hissing. Your boyfriend sneaks up behind her and takes a wallop of a suckle. … Your mother is a mystery. You don’t know how it is she lays eggs and makes milk. You don’t know how it is you look okay, your sister looks lovely, and the new baby your mother is making will be stunning, will be fire, will make hearts snap like celery.

Jellyfish Highway, 2016

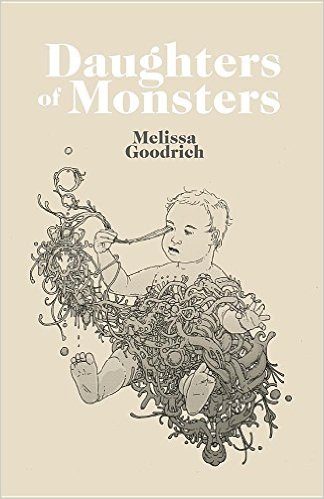

Melissa Goodrich’s debut collection isn’t afraid of monsters. These lines, taken from “Daughters of Monsters,” are visceral and immediately arresting; the title story is the beating heart of Goodrich’s debut collection. It is important that she begins this passage with a bold image of the mother, the monster. It is only after the mother has been sensually grounded that the narrator begins to extrapolate into her many mysteries. In this way throughout the collection, the jaw-dropping strangeness of female characters such as the mother is unveiled, rather than unloaded. There is impropriety here, but never without reason. From the opening story, “She Wants, She Gets,” a retelling of Cinderella in which the protagonist returns not into a woebegone girl but rather into a pile of ash, Goodrich establishes her lack of interest in perpetuating tradition for tradition’s sake. She draws that proverbial line in the sand, fills it with gasoline, and sets it on fire. Some of her stories are speculative while others are realistic. From a flood story that features Noah, his ark, and an iPhone, to a slow-burning apocalypse that forces everyone to head East in gas masks, these are all stories of transformation.

Goodrich explores colors throughout Daughters of Monsters: their power to undercut and unbalance. They bleed into one another, creating new layers. On an aesthetic level, Goodrich’s stories each have their own colors. “Lucky” is the yellowish-green of the poison gas that pursues its characters to the Atlantic. While heat lightning is a flash of green in “For Good,” as are lime-colored bras under crisp white shirts in “School,” yellow-green occupies nearly every page of “Lucky”—one of the collection’s longest stories. There is the purple of the bruise and the grey-purple of its antidote, the great ape’s tongue, in “Anna.” There is the horror of the neutral tone in the titular story, when “you know your luck is beige.”

Goodrich highlights the brown “other” of Istas‘s skin in “For Good,” and of the angels in “Where Dust Storms May Exist.” Here, color is made political:

I guess I didn’t know at first they were angels, or couldn’t think the word exactly because to me they just looked naked with wings—just naked, kids, with wings. Hundreds of them. What they didn’t look like was: white or clean. They didn’t look blond. They weren’t ladies, serene and wearing pleated sashes that ended just above the ankles, bare feet that looked like they’d never touched rough earth. Instead I saw Hispanic. Instead what I saw were two heads. What I saw were two-headed boys, boys with wings, boys who looked maybe twelve, thirteen years old, gangly and naked and nipping and flapping and giving a jolt when they knocked into the wire of their fences, which were tall, and evidently electric. They were stringy-thin. Their heads were shaved down to the scalp. Their feet were stamping, calloused, cut. Their penises flopped under their stomachs as they scurried back and forth in their pens.

Goodrich doesn’t shy away from politics in Daughters of Monsters, to varying degrees of success. Despite all its play with mythology, with Pangaea, with fairy tales and religion, American values are at the core of Daughters of Monsters. Sure, Western religion is playfully deconstructed through stories like “A Dreamless Year of Feeding Animals,” where the omnipresent character of God is allowed to be foolish, destructive, and juvenile as he floods the world and converses with Noah. But always, the United States, with all its endemic stereotypes, remains central to the perspective from which these stories are told: “I didn’t know God made black angels,” the narrator of “Where Dust Storms May Exist” admits, and collectively we cringe. As readers, these cultural biases are uncomfortably familiar.

Body parts and household objects recur throughout Daughters of Monsters. The word “shoulder” appears thirty times over the span of the book. God can be found on thirty-three pages. Scissors cut off a toad’s legs in “Lucky,” find their way first into Christmas stockings in “Anna,” and later twirl from a hairdresser’s fingers in hell. The word “pinwheel” whirls itself through the first three stories in the collection, describing a soul, an ant, and a small girl’s arms.

As in classic fairy tales, animals appear as representations of human emotion and mood, and the deterioration thereof. The quarter-sized animals at the beginning of “Anna” grow larger as the snow falls, eating their caretakers, pushing limbs through doors and windows. They’re inescapable on the ark, unlikely bedmates for Noah, his wife, and his children, until Rebecca grows tired of it, “[throws] the bird doors open and pull[s] back the chains” until the birds fly out, their “breasts bloom[ing] bright against the white” of the snowy sea. Noah, in desperation, takes it a step further:

When the ocean didn’t thaw and God didn’t seem to care anymore, Noah killed a cow and ate steak for the first time in months. How many months? They didn’t know but June was large now, round and hurting. Even she craved meat. Rebecca co-conspired, started a fire, skewered the beef on a spit. The whole family gathered, hungry and nervous. Where was God. June pressed her hand to her stomach, where her angry God-child kicked.

It is the women in Daughters of Monsters who dismember animals in times of distress, from Elsa’s toad in “Lucky” to Papa’s unhatched chicks in “For Good,” and without remorse, as in the titular story: “He tries to lick his beak seductively but his tongue is sort of grey-purple and oyster and way too short. You pluck it out and eat it. He lisps, Yow yewl be sorry. But you’re not sorry. You pluck his scalp feathers and you eat those too.” Because women aren’t made to be loved in Daughters of Monsters. Some of them are horrible, morally and physically, and that’s truly beautiful.

+++

Melissa Goodrich grew up in a dome on a hill in Minnesota, and now lives in the desert with her love and lazy Holland Lop. She received her BA in Creative Writing from Susquehanna University and her MFA in Fiction from the University of Arizona. Her stories have previously appeared in Gigantic Sequins, PANK, Artful Dodge, The Kenyon Review Online, American Short Fiction, and she has a chapbook of lyric poems published by 4th and Verse, If You What. Find Melissa online at her site and on Twitter @good_rib

+

Carolyn DeCarlo has written two chapbooks, Strawberry Hill (Pangur Ban Party 2013) and Green Place (Enjoy Occasional Journal 2015), and co-authored two more, Twilight Zone (NAP 2013) and Bound: An Ode to Falling in Love (Compound Press 2014), with Jackson Nieuwland. Her third solo chapbook, Spy Valley, has just been named a winner in Dirty Chai’s chapbook competition and will be published in their Fall 2016 catalog. Recent writing has appeared in Funhouse, Deluge, Entropy, PANK, and West Wind Review. Her heart resides in Wellington, New Zealand. She is trying to find the joy of living in Maryland.