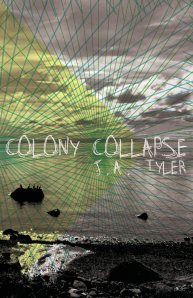

Lazy Fascist Press, 2013

J.A. Tyler’s Colony Collapse is a transformative book. In its opening paragraph, the narrator describes a moment where his brother hands him a note, a “white paper sea sailing a black ship,” which signals the narrator’s dying. The brother then becomes a deer and disappears into the woods. The book that follows concerns itself with the narrator awaiting his brother’s return, mourning him, as he builds shelter after shelter, erecting first one house, then destroying it to erect another, destroying that one, then another, building and destroying and rebuilding in near-solitude as he awaits the return of someone who the reader catches on pretty quickly will probably not return. To describe the plot of this book, though, is in some ways to court a kind of failure, for the beauty of the book and the pleasure to be taken in it is not contained in what happens, but in its language, in the world that Tyler constructs for the narrator to exist in.

In many ways Colony Collapse operates according to a kind of dream-logic. Much like the narrator’s brother, who is constantly transforming into a deer and then vanishing—“only a fleck of white tail disappearing into the trees”—the narrator himself seems to morph before our eyes from deer to boy to man to half-deer and so on. Animals, bears and foxes in particular, take on human qualities, children exist as half-apparitions, and the scenery itself seems to slide around like panels, and it is with a deft hand that Tyler recreates the lucid strangeness of dream, normalizing the strange, and at times strange-ing the normal. But if the language of Colony Collapse is the language of dream, it is also the language of myth. Here is how the narrator describes the building of the “fourth house”:

I built a fourth house underneath a mountain. The mountain was tall but I moved it stone by stone, tree by tree, displaced its bulk until there was a hole I could stand in. I stood in the mountain’s lack and built a house there, this fourth house. I went to my axe and my saw, making planks from trees and using mud for seams. I built a chimney for the first snow, gutters for the first rain. I built shelves where the jam would go. I built cupboards for my magic tricks, for my deck of cards, for my violin and the drippings of music. I built a corner where I could stand. I built a chair where I could sit. I built a bed to cover in a quilt of pine needles and moss. I built my mother to rock me to sleep and my father to cook breakfast in the mornings. I built a picture frame and a picture of my brother inside of it, to keep track of what was missing.

The prose here is typical of the book as a whole. The short, declarative sentences Tyler uses, along with their repetitive structure (I built, I built, I built) is formally reminiscent of oral storytelling; and the way that equal attention is paid to the impossible (moving the mountain by hand) and the particular (pine for planks, mud for seams) thus lending a kind of verity to both, seems to echo the syntax of myth that allows for a world that is at once mystical and recognizable. And the way that the narrator describes the building of his parents with the same declarative speech that he does the building of his chair and his jam shelf has a way of not only further blurring the line between real and fantastic, but also of establishing a kind of free passage between the real and the metaphoric, thus deepening the sense that the narrator is speaking to us from a plane that is different from, or other than, waking existence.

Whether it is the dream-language of myth, or the myth-language of dream, such discourses tend to operate through a kind of blending or blurring. It seems appropriate then that, formally, Colony Collapse is troublesome to classify. On one level it reads like a novel, on another it reads like a series of prose poems, or as one book-length prose poem. And like any good dream-narrative, it is often shifting us from one dream-space to another, so that structurally it becomes a series of boxes within boxes, dreams within dreams, and it is in these places that Tyler’s skill at representing the circuitous nature of dream logic really comes to the fore:

Waking to a dream that is not a dream is what it means to be between you and the you that used to be. My death-dream is of houses and burning, of foxes and bears and fish. My death-dream is a brother delivering a message of dying and then his disappearance. My death-dream is about trying to find him again, seeking truth. My death-dream is about searching for a brother where a brother is not. But these non-death-dreams, they are about deciding what it means to be awake.

There is a conundrum that a book like this must grapple with, and it’s a tough one. As readers, plunged into a dream/myth-world like the one in Colony Collapse, our drive to attribute meaning to the things we are shown there is going to kick in, and if the book gives us weirdness without delivering on the dream’s/myth’s inherent promise of meaning, we may feel cheated. Still, all too often, the delivery of meaning can be a kind of let down, since all of a sudden the beauty and the wonder and the mystery of the dream-world becomes normalized. It is killed by its own explanation. Somewhere around the two-thirds mark of Colony Collapse, we are given glimpses of the world beyond the world of the book, and as artful as Tyler is in the revealing of that other world, I have to admit the book lost some of its magic for me in that moment. And that’s my problem, not the book’s; if that reveal weren’t there, I’m sure I would have been bothered by that. But ultimately that’s the paradox that’s always presented to us with narrative: we want to know what happens, but to know what happens is to come to the end, which is always going to be kind of a letdown; that paradox is just writ large in a book like this one.

Since Freud we’ve become obsessed with the meaning of our dreams. Often, though, in looking for that meaning we seek a too simple explanation for the weirdness of them. Colony Collapse does an admirable job of avoiding falling into the trap of simplicity. I’ve been using the word dream a lot in these paragraphs, and referring to the book’s language as a dream-language, and while that does, I think, accurately describe how the book functions and operates, it is not simply a book about a dream. It’s more complex than that, but to say what it really is, is to risk spoiling the ending ,which, hopefully it goes without saying, does not simply rely on the big reveal—that is, the telling of what it has all been about—but is instead nuanced and strange and touching all at once.

+++

+