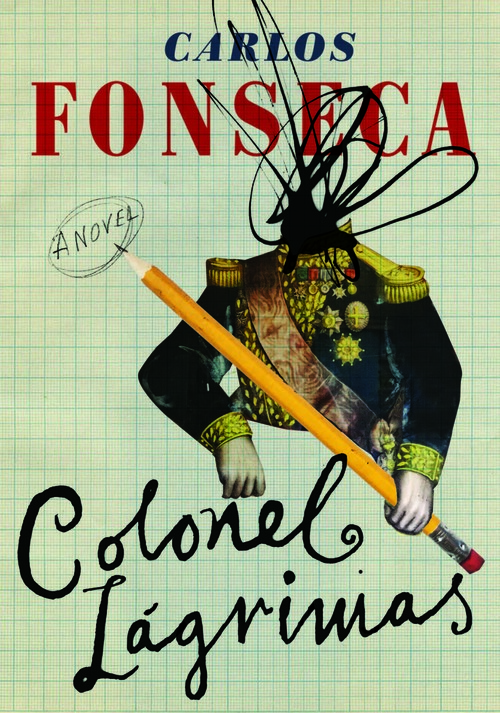

Restless Books, 2016

Like the genius that inspired it, Carlos Fonseca’s debut novel follows an unlikely trajectory: Introduced to the eponymous colonel near the end of his story, the reader assembles a life from episodes culled interchangeably from past, present, and apocalyptic future. Born in Mexico to an anarchist father and actress mother, the Colonel comes of age in tandem with the twentieth century, losing his father in the Spanish Civil War, and running away from his mother to start a new life in occupied France during World War II. Mother and son are eventually reunited, only to be separated again by the contingencies of war, this time in Vietnam. Although he eventually abandons his career as a mathematician, the Colonel continues to work on obscure projects from a secluded retreat in the Pyrenees that either reveal his unraveling mind or mask a much greater revelation.

Based on the life of mathematician Alexander Grothendieck, Colonel Lágrimas eschews historical reconstruction for erudite speculation. The essayistic fictions of Jorge Luis Borges and Roberto Bolaño certainly come to mind, but a more apt parallel might be Julian Barnes’ Flaubert’s Parrot, a biographical work in which the lacunae are just as essential to the narrative as the author’s well-stocked yet ultimately incomplete archive. Fonseca narrates the Colonel’s story through the viewpoint of a seemingly omniscient observer, who may in fact be merely part of a mysterious collective spying on the Colonel, assembling the story alongside the reader, elusive clue by elusive clue. The play of viewpoints gives the novel its dramatic tension as well as its comic relief; even the homeliest aspects of the Colonel’s life are scrutinized as potentially illuminating. When intestinal distress sends the Colonel to the bathroom, the narrator(s) laments being left “out of his secret. We are left with the impossible task of live-announcing a life we do not see.”

At the same time, this moment is emblematic of how elegantly the novel modulates between experience and history, graphing anecdotes onto suggestive narrative patterns. The touchstone for the speaker’s lament is none other than a former U.S. president, cited by the Colonel in a written exchange with a sometime collaborator:

You know, Maximiliano, that this Ronald Reagan […] had the most interesting job before he found success as an actor: he was a football announcer. The strange thing, the magnificent thing, Maximiliano—and here is the point of this anecdote—is that this future president didn’t watch what he was narrating: he simply received bits of information, strung like rosary beads he never saw whole, loose bits of information about a spectacle he didn’t watch, but with a tone he imagined in a kind of blind broadcasting. Our project is a bit like that. Broadcasting for an age without witnesses, a kind of blind narration of this dance of crazies.

Of course, Fonseca’s narration is never blind. For every apparent digression into alchemy, history, philosophy, and literature, there is at least momentary clarity when discrete points coalesce into intriguing connections drawing readers further into the novel’s mysteries:

we wonder how many layers we must peel back to find again the child with straight hair and small hands. Not many. One transverse incision, a slice through the rock of his inhuman passion, is enough to see the stratification of our ludic old man’s emotions.

Far from abstracting the Colonel as a series of points on a graph—or, as suggested above, beads on a string—Fonseca tantalizes with his capacity to discern a whole from incongruous parts. The twentieth century becomes a series of atrocities charting civilization at its supposed pinnacle. The Colonel’s rejection of his native Russian, and his donning of various identities over time—orphan, scholar, soldier, hermit—are defiant gestures for control in a life (and a century) with few surviving constants. In its shifting permutation of the miniature and monumental, Colonel Lágrimas finds the soul in the mathematician and the art in the mathematical. To call it formulaic is to miss the point.

+++

Carlos Fonseca Suárez was born in Costa Rica in 1987 and grew up in Puerto Rico. His work has appeared in publications including The Guardian, BOMB, The White Review and Asymptote. He currently teaches at the University of Cambridge and lives in London. Colonel Lágrimas is his first novel.

+

Megan McDowell has translated many modern and contemporary South American authors, including Alejandro Zambra, Arturo Fontaine, Carlos Busqued, Álvaro Bisama, and Juan Emar. Her translations have been published in The New Yorker, McSweeney’s, Words Without Borders, Mandorla, and VICE, among others.

+

Pedro Ponce is the author of Dreamland, a novel forthcoming from Satellite Press.