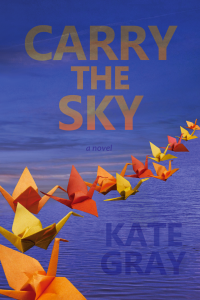

Forest Avenue Press, 2014

“The words I wanted to say were not a prayer,” says 23 year-old Taylor Alta, moments after reciting the Lord’s Prayer in reverence for the striking New England and Mid-Atlantic landscapes that frame Kate Gray’s just-released novel, Carry the Sky, “The words I wanted were about wanting, the opening in the chest, the loneliness.”

Gray’s debut novel revolves around just that: the struggle to find the right words and take the right actions, the loneliness of desire, the weight of love and loss. Our narrators, Taylor, the new rowing coach at an elite Delaware boarding school, and Jack Song, who teaches physics, come in to the new school year at St. Timothy’s both reeling from the death of loved ones and struggling with what they fear are inappropriate romantic desires. The year is 1983, and Song, age 28, is the lone Asian-American teacher at the school; Taylor is a lesbian putting on a mask for the J. Crew-clad prep schoolers, unsure of whose desires to conform to, unsure of what she really wants. Both are adults, but young adults, and for the first part of the novel they exist in a haze of isolation—both good teachers, both trying to be good role models and people, but so caught in the tides of their own experiences that they have difficulty opening their eyes to the realities of their students.

The two seem stuck in their own histories, the time before they faced their first real loss, and Gray’s dreamy, poetic language perfectly captures the languor, the sudden bursts of pain, the slow, subtle drowning that an isolated young adulthood can be. Taylor, an elite college rower, sees her world in terms of rowing and the crew team, while Song frames his in physics and the sciences, but neither is able to carry these models outside of themselves, apply them to the wider world in a way that brings them comfort, makes true sense. And neither knows quite what to do about a cruel case of bullying they observe among their students.

The climax of this novel comes in a rush of thoughts and images that are processed by the reader much the way Gray’s characters experience the events themselves. We are left asking the same questions asked by the teachers: how can we ever predict or prepare for what might happen? How do we know in the moment which details are important, which will stay with us for the rest of our lives? What formulas and patterns can we use to guide us when, as Song says, “no science can explain grief”?

Gray also raises questions about the role of a teacher, specifically a boarding school teacher, whose life, says Taylor, is a series of scheduled events:

…race to breakfast, one set of clothes, race to class, another set of clothes, race to practice, another, shower, race to dinner, another set, back to the dorm, relax, grade, bed, another set of clothes.

Immersion into the prep school environment seems to work to strip identity, reduce both teachers and students to their most basic of parts. What does this mean for these characters, their relationships? How much of themselves can dorm-dwelling teachers really give to their students while maintaining professional distance? How much wisdom does one freshly out of college, only four years older than her students, really possess?

Most important, I think, is the question posed by Song at the end of the novel, once the bullying is nominally resolved, the threat to the establishment over, the administration content to let things rest. Song thinks about the students and wonders, after everything, what he has taught them.

Through Song, Gray explores the Korean concept of hyo, “earth on son”, a son’s responsibility to his parents. This theme resounds throughout the novel, be it through Kyle, the bully’s target, and his own protective instincts, enigmatic senior Carla’s memories of her older brother, or Taylor’s own attempts to please her family. But ultimately, Song turns the concept of hyo around, says “earth on us”—adults and teachers have a responsibility to guide young people, no matter how difficult the course may be, no matter how caught up in their own loneliness they become.

This is not a book to tell you clearly how things happen, to frame the world in black and white, point fingers, or place blame. This is a novel that explores how we process our grief, how we deal with guilt, and how we learn to look outside of ourselves. It is a story about how we see ourselves, learn to live with ourselves, and learn to forgive ourselves, told in luscious prose through two strong narrative voices.

Gray’s background in poetry comes through in her syntax, which at times leans toward the experimental. By and large, her language seems carefully chosen to resonate with and reveal aspects of her characters, be it Song’s clipped emotional tone and sardonic dispensing of nicknames, or Taylor’s tendency to describe everything in passive metaphorical metonymy (“[the bar] was cigarette butts,” “the day of the race on the Schuykill was eights and geese and nervous girls”.)

But Gray’s writing truly shines at its simplest and most honest. She has made no secret of the fact that the seeds of this novel come from her own experiences as a young teacher at boarding school, that the writing of it helped her process events and emotions from her past. “I didn’t want to tell all this,” she says, through Taylor, “the story of how cruel boys can be, the way loneliness tastes sweet and makes you think it’s love. I wish desire hurt like a hangover. I want adults to see past their want and loss. But all I can do is tend a crack I still carry around, a crack that will never fill.”

Carry the Sky works to create that same crack in its readers, and succeeds in telling a haunting story that lingers long past its final page.

+++

+