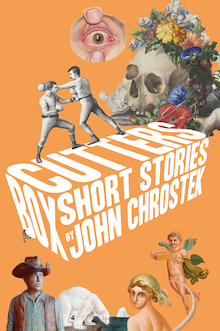

Malarkey Press, 2025

Halfway through John Chrostek’s Boxcutters is a brief, deadpan story in which Richard Nixon wades into a fishpond and becomes a conduit for “the Sight.” Believing himself to be clairvoyant, even though he actually sees the past, Nixon recalls his indifference to a young Black man’s tragic death while he was president. Before he can feel any shame or remorse, however, the vision ends, and he nonchalantly returns home for breakfast.

This story, titled “The Conduit of All Things,” is characteristic of the biting satire found in Chrostek’s genre-defying collection. Ranging from science fiction to psychological realism to myth, the fourteen stories in Boxcutters puncture the notion that powerful people are also the most capable. Though Chrostek’s plots are often eccentric, the stories are nevertheless substantive, as they broach socio-political and economic subjects like miserable living conditions and exploitative jobs. This punchy and fast-paced collection demonstrates how systemic forces, notably—and often comically—ineptitude, crush the most vulnerable.

One of the strongest stories in Boxcutters is “Knucklehead.” The story is set in a town where people can only connect to one another through random, brutal fights. The protagonist, Jim-Jim, has been told by his father that a “good fight keeps you honest, win or lose,” but he privately doubts this is true. While he participates in communal violence, he is critical of the townspeople who need this fighting, rationalizing that he will one day “make them hate it. The whole dumb tradition.” But while Jim-Jim has noble intentions, he is also naïve. Like everyone else, he still believes in the redemptive possibility of violence, unable to see that he can’t break the cycle of violence while perpetuating it.

Jim-Jim’s capitulation to social norms resolves a dilemma that’s also at the heart of “Honey,” a story about an aging actress who has been shattered by Hollywood. Chrostek deftly skewers capitalism’s influence on identity by experimenting with point of view. When the story begins, the protagonist admits “that she forgot her name. It was not Trudie. It was Ophelie.” Ophelie actually juggles three identities: her actual self; Trudie, her stage persona; and Hayley, the character she plays on a middling sitcom. Reinforcing this splintering, the omniscient narrator sometimes calls her “Trudie,” while in others, she is referred to as “Ophelie,” a reminder of the character’s vulnerable position in an industry that humiliates her to make audiences laugh.

These stories might, at first glance, seem overly cynical, but the cynicism is always tempered with humor. This is most evident in the collection’s opening story, “Finding the Joy.” The nameless protagonist steals his neighbors’ Amazon packages, assuring himself that he merely is learning more about his community via their purchases. He explains, “I learned from Kevin V. the value of a good blender. Found out green really is my color.” Eventually, when the protagonist is arrested, he is baffled, arguing that he was a “pillar of the community,” given that he alone knows what everyone in the neighborhood values. The protagonist’s shock is funny by itself, but the story highlights the emptiness of an endless parade of Amazon packages and suggests that consumerism can’t necessarily foster community.

Despite the collection’s emphasis on absurdity, there are still genuine moments of connection and empathy in several stories. In “Glass Spectacle,” Chrostek evokes the magician David Blaine’s famous glass box stunt by depicting an artist, Raulo, living in a similar construction. While people come and go, aimlessly projecting meaning onto Raulo’s performance art, only one woman seems to understand why the artist lives this way. When Raulo and the woman eventually connect, across the park where his box is housed, they share a wordless exchange: “Their eyes met. Raulo’s hand pressed against the glass. He feigned a kind of smile, an intimate, obvious lie.” The lack of dialog amplifies their mutual understanding, creating a luminous mood shift. This same tenderness is evident in the collection’s most moving story, “Vice and Virtue,” a queer reimagining of the Greek myth of Alcides (Heracles) that explores the pain of being bound by fate.

Because the plots in Boxcutters sometimes rely on shock, a few stories are unwieldy. The collection’s closing story, “His Ghostly Portion in the World of Dark,” for instance, presents a future world in which people are addicted to memories. This alarming future mirrors how present-day digital sites such as TikTok create addictive algorithms, but the many graphic depictions of the addiction’s effects on users’ bodies muddle the story’s message. That said, Boxcutters is ultimately a frank and delightfully weird exploration of what keeps people powerless.

+++

John Chrostek is a writer, editor and designer. He is the editor-in-chief of the literary magazine Cold Signal. He attended Bucks County Community College and the Savannah College of Art and Design. Inspired by his working-class background and bizarre life experiences, John explores themes of poverty, madness, memory loss, and capitalism’s many ills. His work has appeared in magazines like Little Engines, Coffin Bell, X-R-A-Y, HAD, Cease Cows, Hex Literary, Maudlin House, Scrawl Place, Deep Overstock, River Heron Review, Taco Bell Quarterly and more. He lives in Buffalo, NY with his partner Amanda and their border collie Madeline.

+

Emily Hall holds a PhD in contemporary Anglophone fiction from The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her creative work and reviews have appeared, or are forthcoming, in places such as 100 Word Story, Cherry Tree, Heavy Feather Review, and Flying South, where she was a finalist for their 2024 creative nonfiction award.