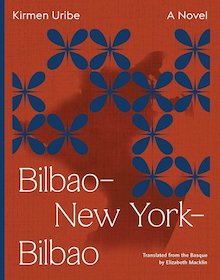

translated by Elizabeth Macklin

Coffee House Press, 2022

When I first visited the Basque Country, a region in northern Spain, I felt very close to the sea, as close as you can get while still keeping both feet on dry land. Kirmen Uribe’s Bilbao-New York-Bilbao gives readers a taste of this sea, as well as an intimacy with the lives connected to it.

Uribe’s novel, which won Spain’s prestigious Premio Nacional de Literatura in 2009, brings together elements of land and sea: “Fish and trees are alike,” the author-narrator begins. “They’re alike because of the growth rings.” In warm weather, both fish and trees grow faster, and in fish, a record of this seasonal increase is preserved as ring formations in the scales. The narrator continues: “What winter is for fish, loss is for humans. Loss makes our time specific for us.”

Particular questions about art, history, and family guide the unfolding of the novel’s central theme. How did the Spanish painter and muralist Aurelio Arteta come to create the painting that Uribe’s grandfather, Liborio Uribe, shows his daughter-in-law, Uribe’s mother, in the Fine Arts Museum in Bilbao on the very day he knew he was going to die? Who was this painter in the first place, and who was the narrator’s grandfather, and why was his boat called Dos Amigos? The narrator offers a clue that links his story to the fading of Basque seafaring traditions: “I felt that Dos Amigos had a novel somewhere inside it, a novel about the fishing world that’s in the process of disappearing.”

Bilbao-New York-Bilbao invites us into the writer’s mind, providing a front-row seat to his various mental and physical journeys. Surprises work themselves into narratives; stories and ideas come together, some durably, others fleetingly. Uribe says “movement is the most important thing, the process that leads the writer to write the novel.” As Uribe moves from one place to another, he stitches together stories related to place and memory, evoking a mixture of emotions.

We sit with the narrator on a plane, on a boat, in a museum. With him we visit Estonia and Scotland, and we consider Velázquez’s Las Meninas and Picasso’s Guernica. The literary equivalent to a fishing net that holds an angler’s catch, ekphrasis binds up this work, bringing together many strands: family and cultural histories, questions about life and art, the sinking of ships and fortunes, and all kinds of texts, from letters and journal entries to emails and Facebook messages.

Uribe tells stories about his uncles, master fishermen who made their way from Ondarroa to Venezuela. Traditions are passed down along with these stories. He reports on the sensitivity of fishermen: “With a glassworker’s sense of touch they knew when a fish would take the hook, and what that fish was like. My hooks, however, rose empty to the boat. I wasn’t sensing when the fish nibbled the bait on the hook.” This seafaring way of life is disappearing. Although Uribe’s grandfathers and uncles were almost all seagoing people, “among us cousins just one chose the sea.”

Telling these passed-down stories, Uribe permits them to circulate in more complex ways. Like fish in water, they are visible in flashes, disappearing only to reappear elsewhere in a different light, as in an aunt’s tale of a lost gold wedding ring later found in the belly of a hake, a story that Uribe refinds in the myth of Herodotus, in the legend of Saint Attilanus of Zamora, and in Tim Burton’s Big Fish.

The language of the Basque country has mysterious origins. The poet Phillis Levin, who does not speak Basque, tells Uribe that his language “looks like a treasure map . . . if you just forget all the rest of the letters and focus in on the x, it looks as if you could find out where the treasure is.” Reflecting on this, Uribe decides that must be the most glorious thing you could say about a language you don’t know, “that it’s the map to a treasure.”

Sharing the Basque literary tradition is, for Uribe, a form of hospitality: “We need to invite the people passing by to come into our house and offer them something there, even if that something is hardly anything. We have the tradition we have and that’s what we have to go on with.” This text is Uribe’s offering, but it is much more than “hardly anything.” He offers insight into his own history and raises questions about the construction of that history, what it takes to preserve the traditions that build you.

+++

+

+