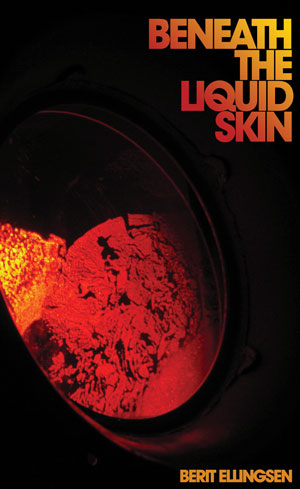

firthForth Books, 2012

The disparate pieces that make up Berit Ellingsen’s new anthology Beneath the Liquid Skin seem to bear little relation to one another. This collection of flash fiction, prose poems, short observations, fragments of tales and a few more fully developed stories has been drawn together from pieces that have appeared in various online journals. Length varies from a few lines to a few pages; genre veers wildly from cold war thriller to science fiction to ‘transgressive fantasy satire’ (Ellingsen’s own description of the wonderful story “The Glory of Glormorsel”).

Certainly there are recurring themes in the collection: the desire for freedom; personal identity and the mutability of form; physical decay and its relationship to the living; the purity of the countryside versus the complicated and duplicitous city. But it’s difficult to say one or the other is the overriding theme of Ellingsen’s writing. Instead, unhindered by the need to yoke her writings to one unifying idea, Ellingsen is free to explore, experiment, play, create, test and move on.

“A June Defection” is probably the most conventional of the stories, a clever piece that seems to comment on the collection itself and the reader’s approach to it. In the story, the narrator and a boyfriend discuss the mystery of a body found in their area years previously—a woman, unidentifiable but with multiple passports scattered around her. Clearly, says the boyfriend, an Eastern Bloc intelligence agent, killed in the process of defecting. But the narrator embellishes this story—the dead woman was another woman entirely, killed and robbed of her identity by the defector, the latter desperate to escape a life of “secrecy and betrayal.” The narrator leaves the boyfriend shortly after this discussion and the reader understands that the embellished story is the narrator’s projection—the bare bones of the actual story padded with the narrator’s own motivations and desire for escape.

This fleshing out is something the reader has to do a fair amount of, in this collection. Ellingsen does not provide us with much information about characters—no backstory, no insight into their thoughts or feelings. We aren’t even told what they look like. Instead, we must infer what we can from their words and actions. In “The Celtic Itch,” Ellingsen provides us with a skeleton of a story and demands that, if we want meaning, we go and get it ourselves. And of course, just as with the narrator of “A June Defection,” we readers might very well be projecting our own needs and desires onto the story, creating meaning rather than uncovering it, and in the process revealing more about ourselves than we do about the tale.

Not that Ellingsen is entirely unhelpful. She may not provide much in the way of physical description of character, but her descriptions of things: landscapes, interiors, even the slow decomposition of dead animals, are loaded with meaning and an absolute delight to read. In these two passages from the Cold War thriller-style “Sovetskoye Shampanskoye,” Ellingsen’s intensely visual descriptions are both beautifully written and useful in providing clues to the mood of the scene and character. Here, from an interior setting:

Unfertilized sturgeon eggs from the warm and muddy waters of the Black Sea, in a leaded crystal bowl with a wide-handled silver spoon, along with sparkling Belarusian Chardonnay—Sovetskoye Shampanskoye—Soviet champagne, warm the teak wood. In the light from the living room candles, the serving cart burns golden. He smiles.

And some time later, outside:

Years of warm smiles and cold handshakes, while ice shrouds and flays the Moskva River and clouds rush across the sky like time.

However, as carefully crafted as the language is, a number of the stories don’t give the impression of having been thought about too finely. Ellingsen says of the collection, “Most of the stories appeared by themselves …” and many do have that sort of natural, unstructured and flowing feel to them.

There’s a sweet, gentle optimism evident in many of the pieces. Characters are generally kind and treat each other well; lovers are generous and open-hearted, happy to make sacrifices for one another. As the narrator says in “The Glory of Glormorsel,”perhaps the most thematically challenging of the pieces in this collection, “We are nothing but kind to each other, because without kindness we are nothing.”

This optimism is evident also in the way Ellingsen explores the twin themes of mutability and decay. In her hands, nothing is repulsive. In “The Love Decay Has for the Living,” a man sprouts mushrooms from an open wound, which serve as a magical ingredient in his lover-chef’s cooking. It’s not difficult to see how this could make a reader queasy. But in fact this is a sweet love story filled with generosity, self-sacrifice and gentle regret.

Similarly, “Still Life of Hypnos,” is ostensibly a tale of rot and decay, yet Ellingsen’s language is lush and “alive” as she describes the gradual decomposition, in their various ways, of fruit, flowers, insects and animals. But the decay is neither repugnant nor negative—it’s actually rather lovely and it seems such a natural end point to life, that it’s almost a part of it.

While not all the stories in Beneath the Liquid Skin are completely successful—some are quite baffling and likely to leave the reader struggling to find some clue to hang meaning on—overall, this is a collection of playful, brave, complex and exquisitely written pieces. A real treasure trove.

+++

+