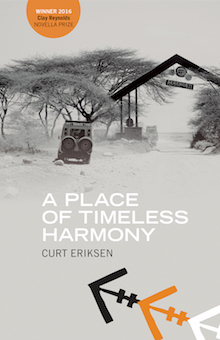

Texas Review Press, 2017

In the short span of a novella, A Place of Timeless Harmony peels back the layered vulnerabilities and illusions of a couple on an illicit getaway to the hostile Serengeti wilderness. An intimate and marvelously-detailed work by Curt Erikson, A Place of Timeless Harmony won the Clay Reynolds Novella Prize in 2016 and was published this fall.

On the surface, much of the plot appears cliché: Richard, a wealthy older man, and his lover, Sophie, a girl in her twenties, steal away from Richard’s wife and teenage twins to give themselves the short-lived luxury of a couple who have all the time together in the world. But the two are suffering from a recent and major rift — an abortion “Sophie had so reluctantly agreed to in the end” that increasingly highlights the “weary seepage of faith in any real future” together.

Counterbalancing Sophie’s regret is the revelation that Richard suffers from another unwanted growth — a recently discovered pancreatic tumor. This he hides from Sophie and denies himself, having been warned by doctors to cancel the trip and proceed with surgery to determine the seriousness of the prognosis. But he puts it off, telling himself the trip will be relaxing, and beneath that, sensing he likely won’t get this chance again. Sophie, too, is nursing a secret. Early on in the trip, resenting the loss of her pregnancy, she begins a flirtation with one of the local guides.

The story is told in short sections, alternating points of view between Sophie and Richard. Each small section reveals more about Richard’s prognosis and Sophie’s Mozambique fling. Each feel pressured to reveal their secret to the other, though the timing is ultimately never right. The disparate weight of what each is withholding is reflected in their relationship dynamic. Although each point of view is given equal page space, the characters’ development is anything but equal. Eriksen gives greater detail of Richard’s profession, how he made his money, how he feels about his business partners, and his family back home, whereas the reader learns almost nothing about Sophie’s life outside of her relationship with Richard. She is painted as naïve, “Struggling a bit with the child-proof cap, she was so nervous and exited to be able to so something” when Richard is overcome with sudden pain. He holds on to Sophie “like a boy flying a kite” and her efforts over six months to learn Swahili for the trip “were regarded by Richard as another one of her many caprices. Which he would always be happy to indulge.” The one indulgence he cannot allow her, it seems, is to take on the complex role of motherhood. This uneven dynamic further underscores the nature of their relationship.

Midway through the novella, the action accelerates as the two split off onto different quests: Richard to secretly visit a healer and Sophie to find the lion that has eluded them so far in their sightseeing. Although Richard scoffs at everything on the faith spectrum, still he is compelled to seek out this touted healer,

an 80-year-old former priest of the Lutheran Church who’d had a vision. In the vision Ambilikile Mwasapile was informed that he could work wonders using the roots of the mgamriaga, or poison arrow, tree. So he went into the bush — where he followed the visionary instructions he had received — and distilled a potion that thousands of Kenyans and Tanzanians had come to drink in the hopes of ridding themselves of all sorts of chronic conditions, including AIDS, ulcers, diabetes and high blood pressure. And even cancer.

He is driven through the ruins of the of the healing boom, miles of abandoned car bones and pulverized vegetation, all the while denying his hopefulness and telling himself that he’s there just to see, not believe, with the same omnipresent distance he keeps from the truths of his own life.

Meanwhile, Sophie is chasing an elusive lion. She “didn’t hunger for violence, but she did want to see some action.” Ultimately, though, what she does witness is quite violent — a gloriously intense and gory hunting scene. Earlier in the book, the reader is told that Sophie “was trusting of Richard in a way that sometimes made Richard feel like a predator.” But what keeps the scene from becoming metaphorically obvious, is that Eriksen turns Sophie’s reflections further inward, comparing the unexpectedly downed lion to her discarded fetus.

Even if it couldn’t feel the pain, the thought of its flesh being scraped and sucked clean — scraped and sucked clean until nothing was left to indicate that it had even been there in the first place, nothing that could confirm that it had ever existed — chilled her, overwhelming her with the crushing guilt once again.

To prevent the decay of their relationship with dishonesty, the two had initially vowed to be fiercely honest with each other. But like the Serengeti predator and prey, the characters are anchored to their own evolutionary calls and practices, instincts that supersede sentiment or intention.

Sophie, who is vaguely writing a book about the trip, asks herself: “Who would be interested in buying something she wrote about an adulterous safari in Tanzania?…Or that of the possibly futile search for one lone male lion in the northern Serengeti?” It’s a tongue-in-cheek line, as it precisely sums up Eriksen’s book. Fortunately, the personal nature of the novella — the story of this particular man and this particular woman — make for a fascinating read.

+++

+